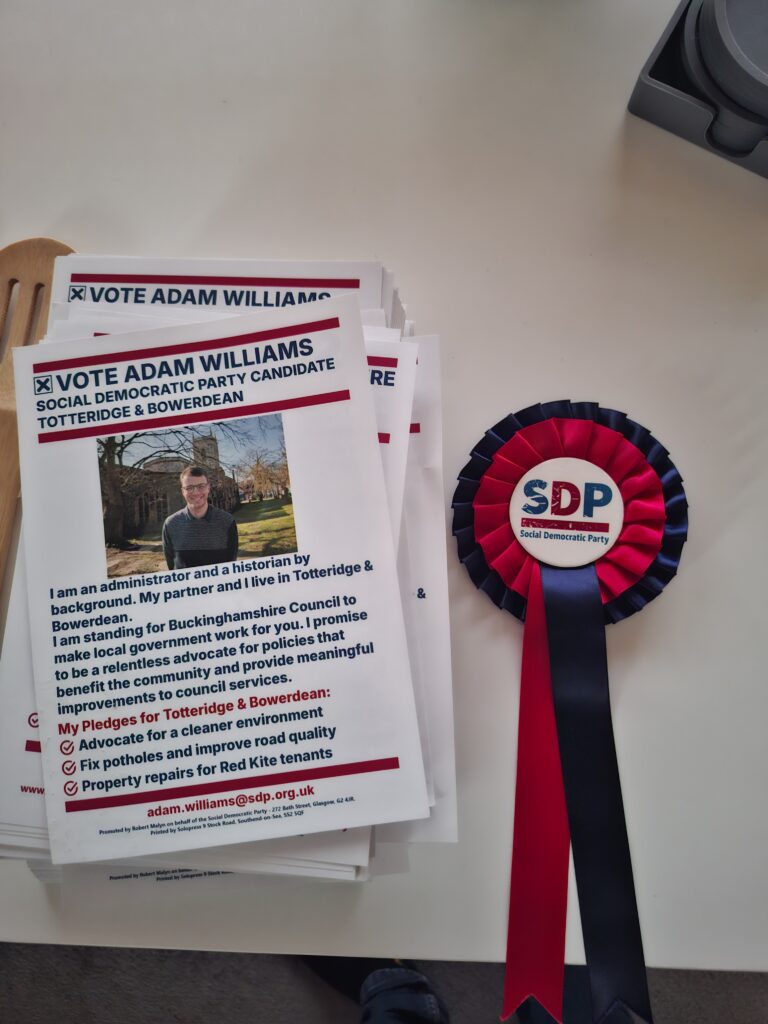

We spoke with Adam before the recent local elections when he was a candidate for the SDP in the Totteridge and Bowerdean ward of High Wycombe, for Buckinghamshire Council. We catch-up with him for his tales from the campaign trail.

“I am incredibly grateful to everyone who came up to High Wycombe to support me, especially since it’s an absolute hike to campaign in my ward”

You ran in the elections in May. Looking back what is your main memory of the campaign?

The feeling of achievement when I finished leafleting, my feet were killing me, I had one volunteer left and we’d just put through my last leaflet, and I was just so happy to have managed to reach my goal of covering the whole ward in SDP leaflets. I am incredibly grateful to everyone who came up to High Wycombe to support me, especially since it’s an absolute hike to campaign in my ward (It’s not called High Wycombe for no reason!)

The seat was won by Wycombe Independent’s and has received some press coverage. Did you have much interaction with other candidates or parties during the campaign?

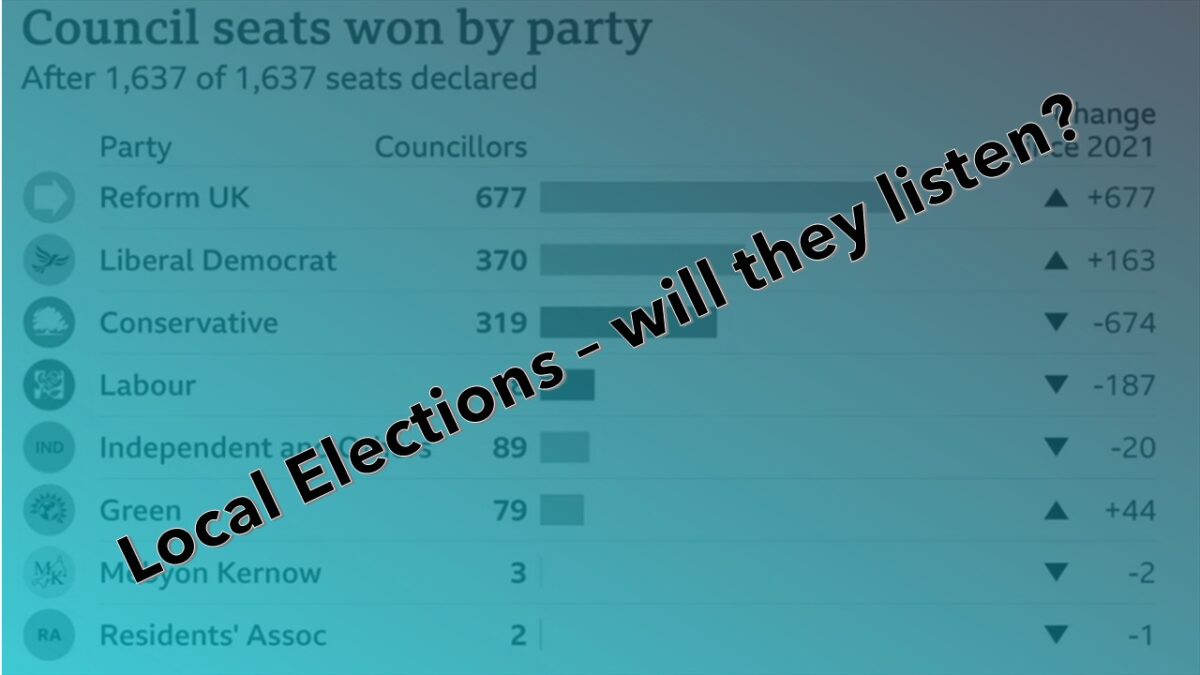

My ward was a battleground between the Liberal Democrats and the Wycombe Independents with the occasional Labour sign. The Conservatives and Reform were non-existent and didn’t even turn up to the count. I interacted with all three of the other parties who actually turned up and put some work in and I got on very well with all of them.

The thing about local elections is that they all wanted to improve our local area, they just differed on how that should be done, so I appreciated the camaraderie.

The Lib Dems in particular were very kind to me, and they actually stood up for me online! I got a lot of abuse and harassment from Reform voters on Facebook but the Lib Dems and some of the other Buckinghamshire Independents supported me in my comment section. The abuse from Reform supporters was a bit of an eye-opener for me. As a party we get a lot of comments about how we should work with them or alternatively, merge, however after what I experienced I am disinclined towards that now.

“I only received one comment on the doorstop about Gaza, and I responded with SDP policy, that the issues in the Middle East won’t be solved in Buckinghamshire”

Do you have any funny stories or interesting encounters from campaigning?

I received a vaguely threatening email from the Palestine Solidarity Campaign in High Wycombe about signing their petition to force Buckinghamshire Council to disinvest from Israeli companies. I ignored it because I don’t engage in sectarian politics that has nothing to do with our local area, however, because I did so, my name and picture appeared in red in a video that the PSC produced, so that was an interesting experience!

I only received one comment on the doorstop about Gaza, and I responded with SDP policy, that the issues in the Middle East won’t be solved in Buckinghamshire and that we take a pro-British foreign policy outlook. I also ended up quoting Treebeard from Lord of the Rings at the gent who asked me the question – “I am on nobody’s side, because nobody is on my side” and he actually went from being a bit aggressive about the issue to then nodding, saying fair enough and asking me about potholes and the police!

What would you say to anyone thinking of becoming a candidate?

If anyone is tired of the situation in our nation and wants to try and improve things, but is scared to take a stance, don’t be. There’s a buildup and an almost fearful atmosphere about being a candidate, and the day before my first leafletting activity I was actively terrified of what I would face. However, with the support from both my partner and my party I managed to get out and face it, and I found that actually it wasn’t too bad! It’s quite an enjoyable experience and makes you feel like you -can- make a difference.

“Now it’s all about long term growth and building up the party infrastructure in High Wycombe”

What are your hopes now for your involvement in politics, for Totteridge and Bowerdean, for High Wycombe, and for Buckinghamshire?

I received 34 votes in the election, not an amazing result by any margin but I was only 96 votes behind the Conservatives, so I’ll take that. Now it’s all about long term growth and building up the party infrastructure in High Wycombe. This town is crying out for competent leadership and investment in its future, and I believe that the SDP can provide that, we just need to grow our membership in the area.

I have also started up a full-time position within the party as it’s Campaigns Organiser, I will be working on the ground across the country to help improve our chances of winning elections and providing this country with a genuine alternative political choice. Reform have shown that they don’t have the ability to maintain a coherent policy or governmental position and I worry that as time goes on, all of the councils that flipped to them will struggle to function.

The SDP is on the rise, it’ll take time and a lot of hard work, but it will be worth it and we will break through. We have to, the country and our very future depends on it.