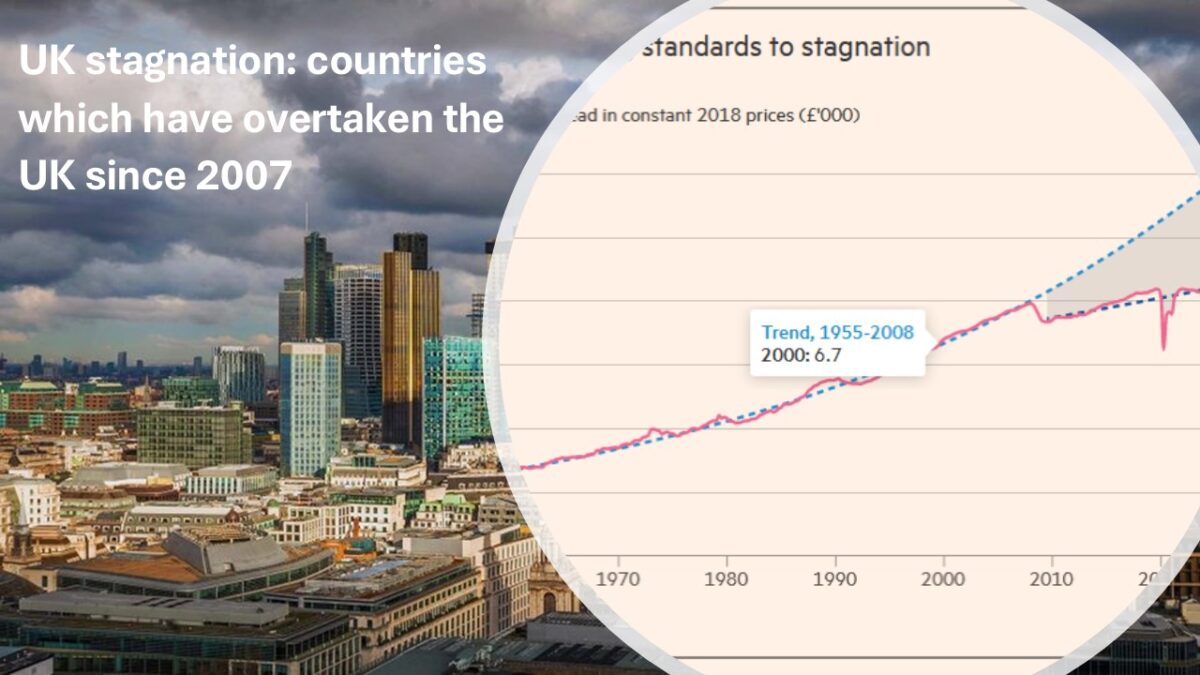

Sam Bidwell on how we can really revive British industry.

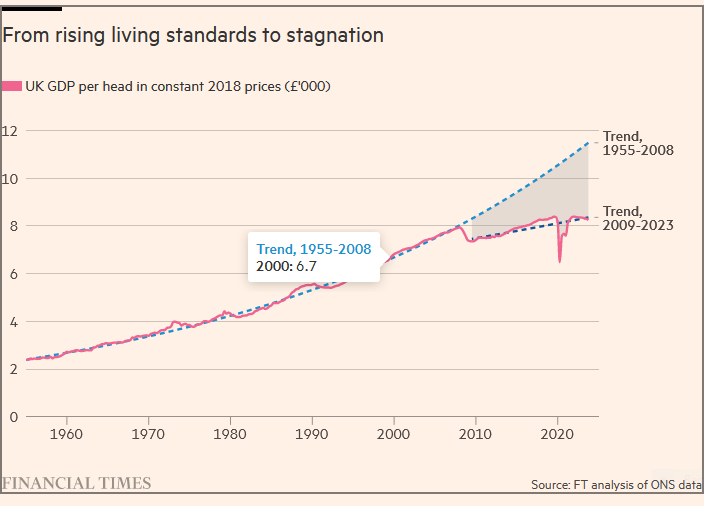

“By the late 19th century, Britain was falling behind the United States and Germany. GDP growth slowed to less than 1% between 1899 and 1914”

People across the political spectrum say that the UK needs an industrial strategy. In fact, it was industrial strategy that killed our industry in the first place – Attlee is more to blame than Thatcher.

According to the popular narrative, British industrial decline started in the 1970s and 1980s, as free trade and neoliberalism shifted us towards a more globalised economy. Today, advocates of industrial strategy argue that Government needs to intervene to redress the balance.

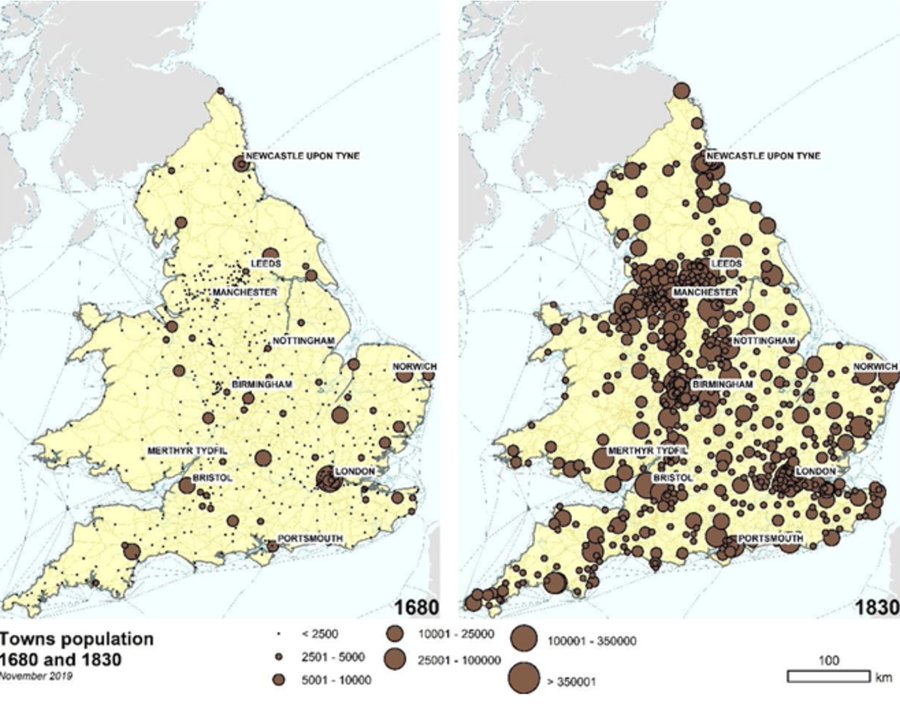

In fact, Britain’s relative industrial decline starts much earlier. By the late 19th century, Britain was falling behind the United States and Germany. GDP growth slowed to less than 1% between 1899 and 1914, while productivity growth fell by two-thirds between 1871 and 1914.

Though it had led the way on industrialisation (more on this later), the UK couldn’t compete with the mass production of the US and Germany. Britain had fewer natural resources and a more skilled workforce, while American firms could rely on cheap resources and cheap labour.

Britain’s relative industrial slowdown was accelerated by the Great Depression. Heavy industry declined by a third between 1929 and 1930, with unemployment doubling from 1 million to 2.5 million. In cities like Glasgow, unemployment rose as high as 30 percent.

“In the Midlands and parts of the south, industry boomed in the 1930s – with specialisms in automobiles and household electrical goods. In 1936, Leicester was actually the second-richest city in Europe”

The decline was particularly acute in the industrial areas of Britain’s Victorian heyday, such as Lancashire, Yorkshire, South Wales, and Scotland. Coal production in Lancashire fell by 43%. Ship production in the north-east of England fell by 90% between 1929 and 1932.

But that didn’t mean that industry was declining everywhere. In the Midlands and parts of the south, industry boomed in the 1930s – with specialisms in automobiles and household electrical goods. In 1936, Leicester was actually the second-richest city in Europe.

It was true that Britain couldn’t compete with the mass production of the US and Germany – but it could lead the way again on high-quality, high-skilled industry. The social effects were incredible – between 1923 and 1937, Birmingham’s workforce grew at double the national rate.

“The Attlee government saw the success of the Midlands as damaging to traditional industrial regions. In 1945, it passed the Distribution of Industry Act”

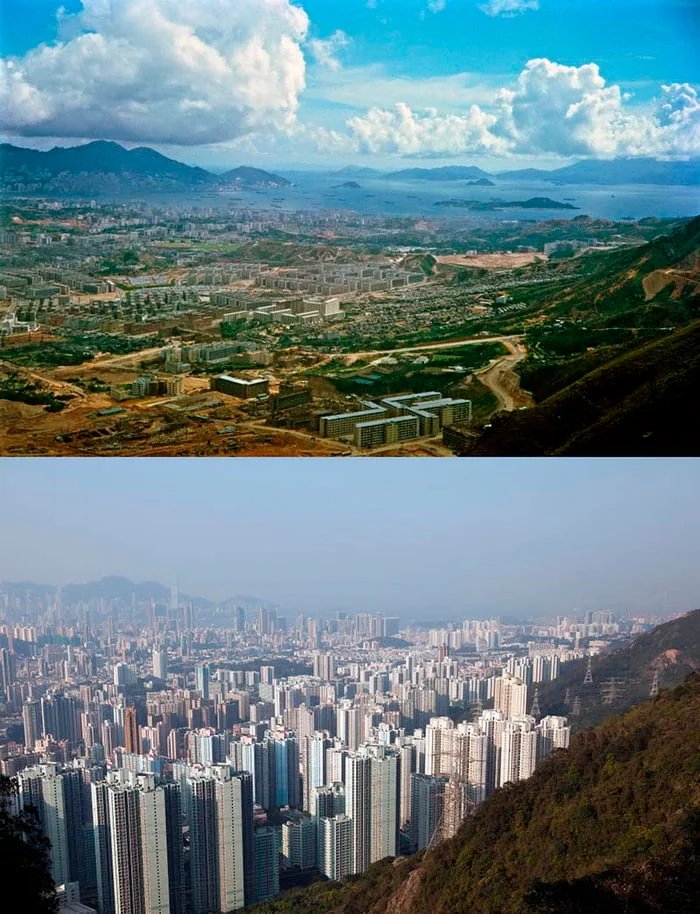

From 1911-1954, the West Midlands grew its economic output faster than any other region of the country – by the 1960s, Birmingham wages were higher than in London. Nearby Coventry fared similarly – in 1953, it had an unemployment rate of 0.8%. British industry was back.

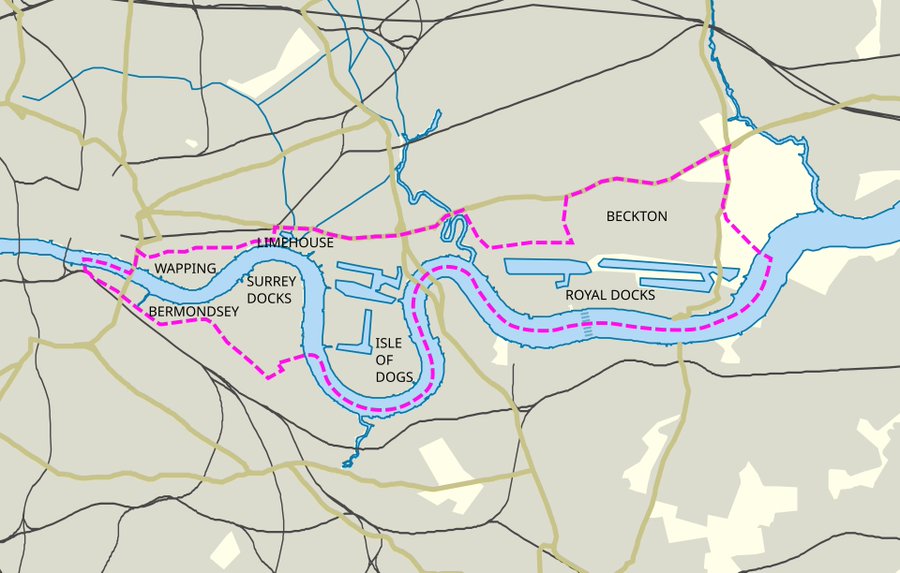

And then came the industrial strategists. The Attlee government saw the success of the Midlands as damaging to traditional industrial regions. In 1945, it passed the Distribution of Industry Act, which aimed to push development away from ‘congested’ areas like the Midlands.

The Government required that any factory set to be opened or expanded in a ‘congested’ area would be reviewed by the Board of Trade – which would aim to push industrial development back to places like Lancashire and South Wales. The results were predictable – and depressing.

“In 1946, the West Midlands Plan set Birmingham a population target lower than its current population. In 1964, Harold Wilson restricted the development of office space in Birmingham for 20 years”

Of the ‘Industrial Development Certificates’ rejected by the Board of Trade, just 18% actually relocated to declining industrial areas. 49% of refused projects downsized their ambition to avoid government oversight. 31% of projects were scrapped entirely.

For every job re-directed to old industrial areas, several more were prevented. In 1946, the West Midlands Plan set Birmingham a population target lower than its current population. In 1964, Harold Wilson restricted the development of office space in Birmingham for 20 years.

“Forcible relocation of growth, and subsidy for declining industries, left British industry inefficient and uncompetitive”

Industrial strategy also meant subsidising inefficient ‘old’ industries, such as coal and steel, at the expense of new industries, such as cars and household electrical products. The nationalisations of the 1940s and 1960s were designed to preserve old industry at all costs.

Forcible relocation of growth, and subsidy for declining industries, left British industry inefficient and uncompetitive. The burgeoning ‘advanced manufacturing’ boom of the 1930s was killed by the nostalgic, backwards-looking industrial strategy of the late 1940s.

These inefficient and expensive controls were eventually lifted by the Thatcher governments. Yes, British industry did shrink in the 1980s. But if it had been allowed to adapt, improve, and emerge organically in the previous decades, it would have remained competitive.

“we shouldn’t try to decide where industry ought to be based on pre-conceived ideas about where growth “should” happen. Industrialisation completely changed Britain’s economic geography”

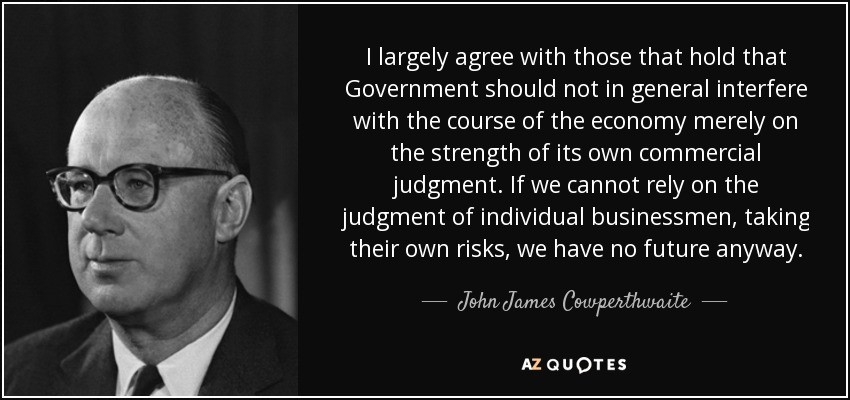

If we actually want British industry to succeed, we shouldn’t follow in the footsteps of the 20th century industrial strategists. We should learn from the conditions which birthed British industry in the first place – which actually means less government control, not more.

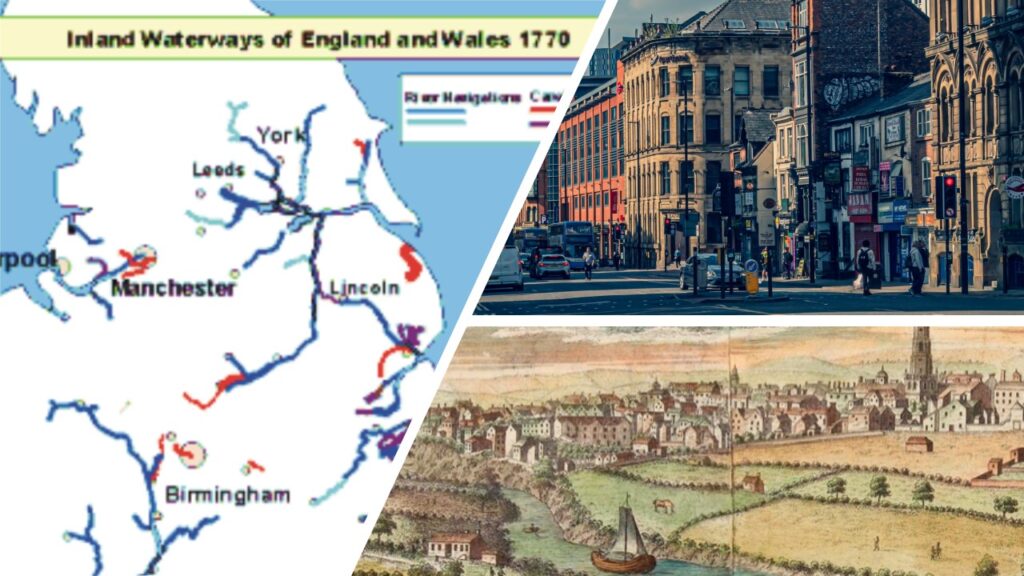

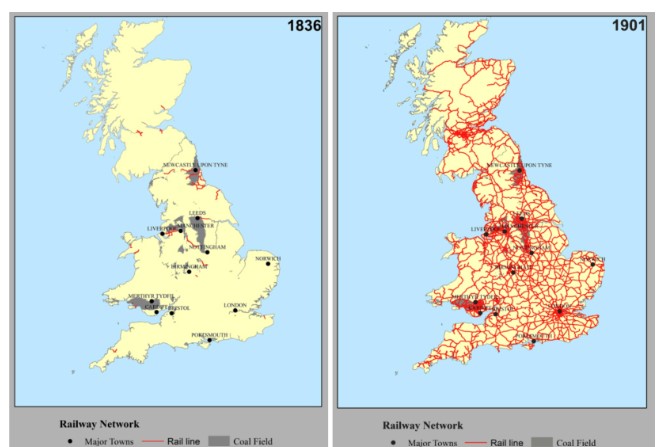

First, we shouldn’t try to decide where industry ought to be based on pre-conceived ideas about where growth “should” happen. Industrialisation completely changed Britain’s economic geography – cities like Liverpool and Manchester barely existed before the 18th century.

People were able to move to where economic opportunity emerged – and the we didn’t try to direct that growth. Today, that means liberalising our housing market – allowing housing supply to emerge where people want to live, not where the Government thinks that they should live.

“Our current regulatory environment punishes companies that trial new products here, with lengthy processes of consultation, review, and assessment. Instead, we should be removing regulatory blockers”

Second, we should embrace and encourage investment in innovation. The Industrial Revolution was driven by investment in new technologies designed to reduce dependence on high-cost labour – such as Watt’s steam engine, which could do the work of 21 manual labourers.

Our current regulatory environment punishes companies that trial new products here, with lengthy processes of consultation, review, and assessment. Instead, we should be removing regulatory blockers – and reducing tax on innovative firms in cutting-edge fields.

Third, we should make it easier to build the infrastructure that powers industrial growth. In 1846 alone, Parliament approved around 9,500 miles of private railway construction, the equivalent of 63 HS2s. We must relax planning rules around major infrastructure projects.

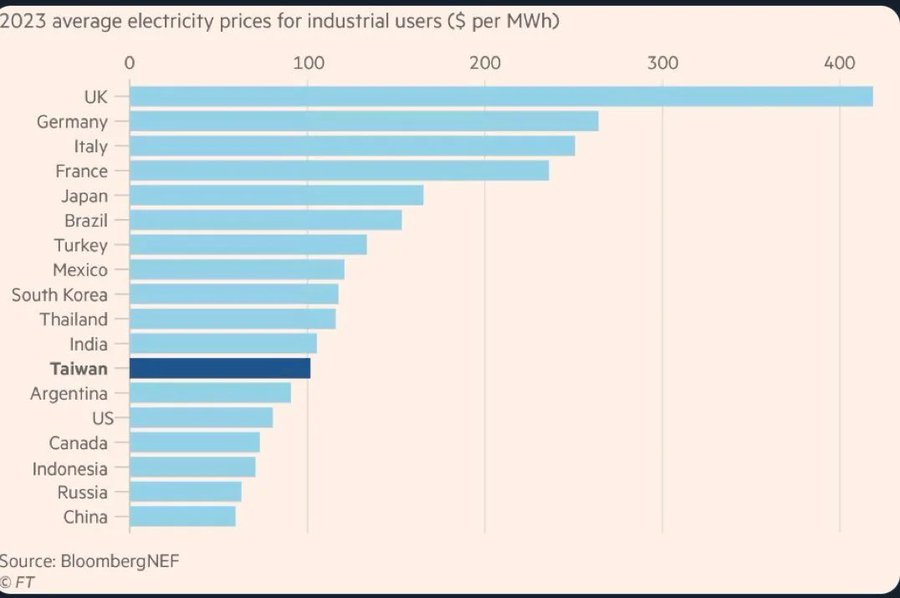

Fourth, we must address energy costs. The Industrial Revolution was powered by cheap coal – low energy costs kept industry competitive. Today, the UK has the highest industrial energy costs in the developed world – killing businesses in energy-intensive sectors such as steel.

“The Industrial Revolution was powered by cheap coal – low energy costs kept industry competitive. Today, the UK has the highest industrial energy costs in the developed world”

This also has enormous implications for our ability to host AI infrastructure, which is similarly energy-intensive. If it wants British industry to compete, the Government should make energy cheap – particularly by bringing down construction costs for nuclear energy.

Finally, we should not try to direct the economy based on what we think industry “should look like”. We should not be picking winners – whether sectors, businesses, or regions of the country. This will be expensive, and it won’t work – as 20th century industrial decline shows.

Reproduced with kind permission of Sam Bidwell, Director of the Next Generation Centre at the Adam Smith Institute, Associate Fellow at the Henry Jackson Society, although views are his own. Sam can be found on X/Twitter, on Substack, and can be contacted at s.bidwell.gb@gmail.com. This article was originally published as a X/Twitter Thread at https://x.com/sam_bidwell/status/1859560533608874311