In the third part of Dan Heaton’s thesis discussing the United States Electoral College, he looks at the Pros & Cons of the Electoral College.

CHAPTER 2 – NOT A PERFECT SYSTEM – THE PROS & CONS OF THE ELECTORAL COLLEGE.

“The impetus for abolishing the electoral college is as strong as it is simple. No sane electoral system awards victory for second place. Indirect presidential elections made sense, if ever they did, only in the early American republic. Voters today should be trusted to cast a straightforward vote for a presidential candidate rather than for a panel of occasionally faithless and invariably faceless electors.” (1)

This view expressed by Professor Jim Chen of the University of Minnesota Law School on 22nd November 2000 in light of the Florida fiasco has been echoed by numerous academics and commentators, both legal and political, since the 2000 election. The case for the abolition or reform of the Electoral College has been argued, if out of sight of the public, ever since its creation. There are those who believe that the Electoral College is inherently flawed and should be abolished out of principle and there are those who believe that it should be abolished or reformed because it is damaging democracy. There are however, numerous advocates of the Electoral College who see the events of November 2000 as merely a blip in an otherwise fair and equitable system which allows the people a voice but also maintains the federalist nature of the Constitution and that it should be maintained at all costs.

In this chapter I shall assess the disadvantages of the Electoral College system as voiced by its detractors and the its advantages as espoused by its supporters.

“They always voted at their Party’s call

And never thought of thinking for themselves at all:

As an institution the Electoral College suffered atrophy almost indistinguishable from rigor mortis.”

The Disadvantages of the Electoral College.

The Faithless Electors.

One of the main arguments against the Electoral College put forward by its opponents is the issue of faithless electors. They find it to be an affront to the practice of popular elections that an elector pledged to vote for one candidate should then cast their vote for another against the wishes of the electorate. Mr Justice Jackson in his dissenting judgment in the case of Ray v Blair (2) (1852) stated the role of elector as he saw it historically:

“No one faithful to our history can deny that the plan originally contemplated, what is implicit in its texts, that electors would be free agents, to exercise an independent and non-partisan judgment as to the men best qualified for the nations highest offices. This arrangement miscarried. Electors, although often personally eminent, independent, respectable, officially became voluntary party lackeys and intellectual nonentities to whose memory we might justly paraphrase a tuneful satire:

They always voted at their Party’s call

And never thought of thinking for themselves at all:

As an institution the Electoral College suffered atrophy almost indistinguishable from rigor mortis.” (3)

Thus as Justice Jackson states so eloquently it is rare that an elector votes against their pledged candidate. However, over the years, the faithless electors have continued to appear sporadically and for their differing reasons, although fortunately none as yet have made a difference to the outcome of an election. The occasions when electors have not fulfilled their pledge may be rare but have occurred as recently as 2000. The fact that the political party organisations have continued to nominate people who could not be trusted remains astounding. Here are some instances of faithless electors from recent the last century:

- 1948 – Preston Parks, a Democratic Party from Tennessee, voted for Governor Strom Thurmond of the States’ Rights ticket instead of Harry S. Truman.

- 1956 – W. F. Turner, Democratic elector in Alabama, voted for a local judge instead of Adlai E. Stevenson.

- 1960 – Henry D. Irwin, an Oklahoma Republican attempted to stop Kennedy from being elected by organising conservative Democrats to vote for Harry Byrd , the Democratic Senator for Virginia. However, in the end only he voted for Byrd and Kennedy was elected.

- 1968 – Dr Lloyd W. Bailey, a Republican elector from North Carolina, voted for George Wallace of the American Party instead of his pledge Richard Nixon. He alleged that he did this because the Congressional District in which he lived had voted for Wallace, but it is believed that he was against the incoming Nixon appointing Henry Kissinger. (4)

- 1972 – Roger MacBride, a Virginian elector for Richard Nixon decided to vote for John Hosper of the newly formed Libertarian Party.

- 1976 – Mike Padden who was a Washington Republican, pledged to vote for Gerald Ford, who instead voted for Ronald Reagan bizarrely as a protest against the winner, Democrat Jimmy Carter, in order to highlight his own Pro-Life views.

- 1988 – Margarette Leach, a Democratic elector for West Virginia, decided to highlight the fact that electors could vote for whoever they like by reversing her vote and voting for Senator Lloyd Benson of Texas {the Democratic Vice-Presidential candidate} for President and Michael Dukakis {the Democratic Presidential candidate} for Vice-President. It was of no consequence however, as George Bush Senior had already won.

- 2000 – Barbara Lett-Simmons, an Al Gore pledged Democratic Party elector from the District of Columbia, abstained by casting a blank ballot, presumably in protest at the Florida fiasco.

Some states have tried to circumvent the potential problem by endeavouring to bind their electors through their state laws. New Mexico, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Washington now demand that electors pledge to vote for their party and have sanctions available for breach. The District of Columbia, Florida, Massachusetts, Mississippi and Oregon all require a formal pledge but do not back this up with any legal sanctions. Alabama, Alaska, Colorado, Maine, Maryland, Montana, Vermont and Wyoming direct their electors to support the winning ticket and California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Michigan, Ohio, Virginia and Wisconsin direct the electors to vote for the party which they represent. (5) [CRS Report for Congress RL 30804 p9]

Thus 24 of the 50 states do not impose upon the electors any duty to vote in a particular way and in effect leave them as free agents. It is also unclear as to whether the sanctions imposed by some states are constitutional. However, the Supreme Court in Ray v Blair (1952) (6) ruled that a state can mandate a political party to exclude from their nominees for electors anyone who refuses to make a formal pledge to vote for their candidate.

The faithless elector argument espoused by opponents of the Electoral College undoubtedly has some merit because potentially, in a close election, if enough electors broke their pledges then they could affect the result of the Electoral vote and the presidency. However, no elector has yet managed to change the outcome of an election and most faithless electors have simply cast bizarre votes as protests, with the outcome of the election already decided.

The fear of a potential coup by faithless electors could be circumvented without changing the essence of the Electoral College, by adopting an automatic plan. Under such a scheme, which I will assess in more detail later, the Electoral College votes are simply awarded on the basis of the statewide ballot with the intermediary office of elector being abolished.

“This occurred in 1992 to Bill Clinton because of the strong candidacy of Ross Perot. There was a clear Electoral College winner but Clinton received less than 50% of the popular vote”

The Election of a President Who Fails To Receive a Majority of the Popular Vote.

Opponents of the Electoral College argue that the system allows the possibility a candidate being elected with less than 50% of the popular vote, a plurality winner. This is again a meritorious argument with minority winners becoming more likely with the rise of third party candidates.

A minority President can be and indeed has been elected in three ways. Firstly, in 1824 a minority President was elected because America was so divided that there were more than two strong candidates. No candidate received a majority of electoral votes and so Congress was forced to decide from amongst the candidates, whom should be President, eventually selecting John Quincy Adams.

Secondly, it is possible to elect a minority President, if, as in 1888, one candidate wins heavily in some states and loses narrowly in others, thus whilst winning the popular vote, losing in the Electoral College.

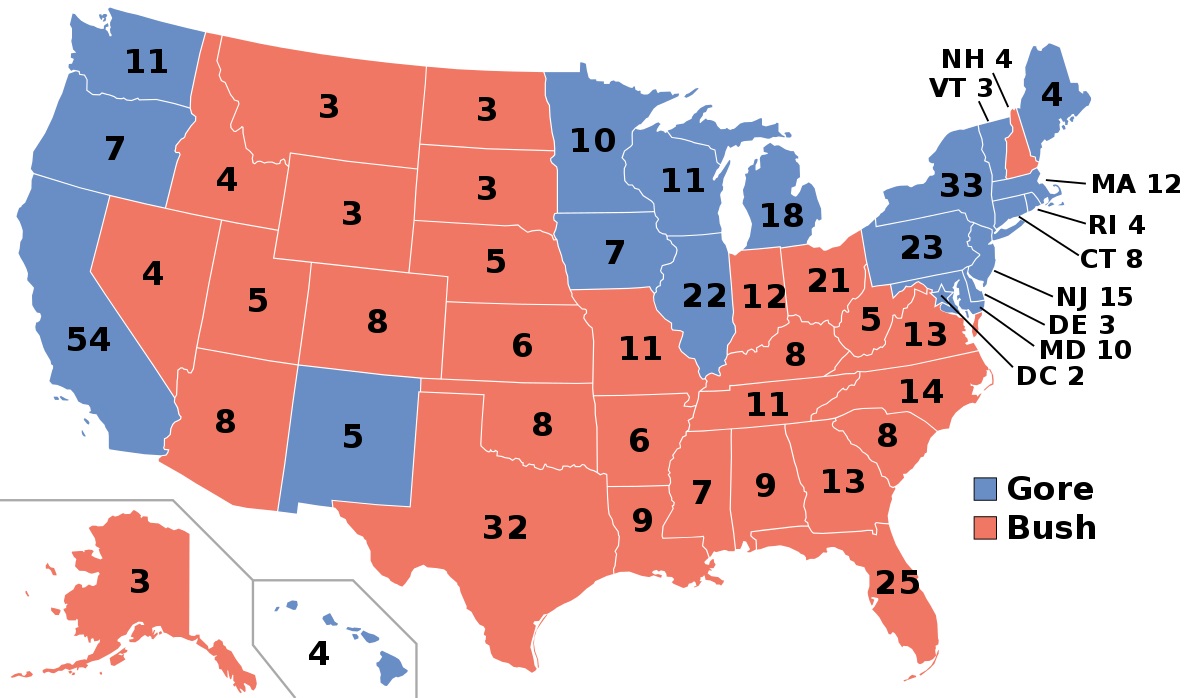

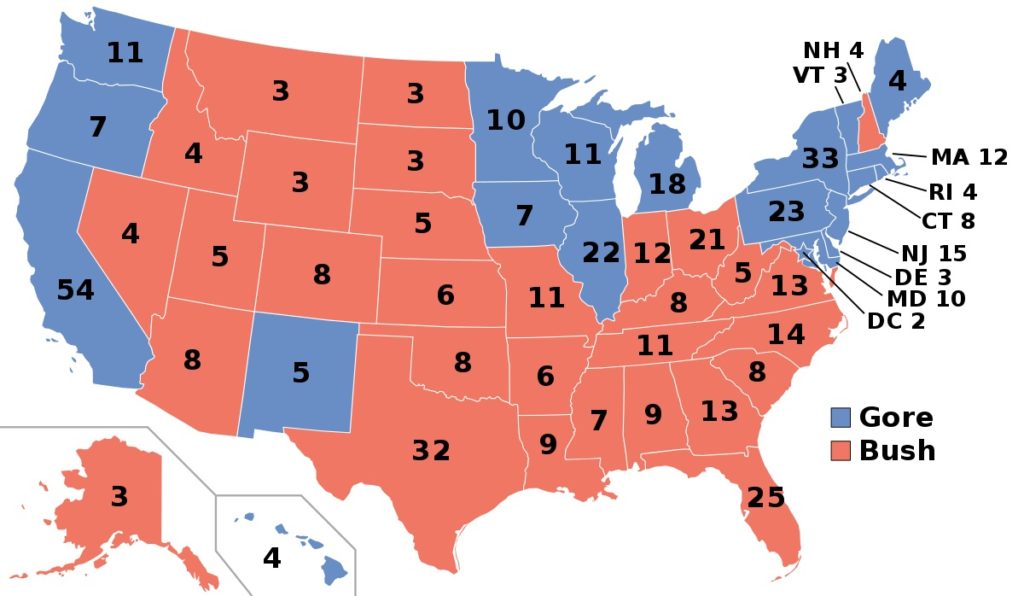

Thirdly, it is possible to elect a minority President whenever a third party candidate takes enough popular votes away from the two main party candidates that even if there is a clear popular and electoral winner, in fact the winner still does not obtain a majority of the popular vote. This occurred in 1992 to Bill Clinton because of the strong candidacy of Ross Perot. There was a clear Electoral College winner but Clinton received less than 50% of the popular vote. Indeed, in 2000 whilst Al Gore did obtain more popular votes than George W Bush he only obtained 48.38% of the national popular vote, primarily because of the Green Party candidate Ralph Nader who polled 2.74% of the national vote.

The possibility of electing a minority President will not be diminished, simply by abolishing the Electoral College. The situation could still occur in a direct election. The only way that a majority President could be guaranteed would be by having second ballots which would be expensive or by using a preferential ballot paper on which candidates are ranked in order of preference. I will assess the viability of such a proposal later in this work.

A Candidate Can Win The National Vote But Lose The Election.

The 2000 Presidential Election was not the first time that a candidate has been elected having received fewer popular votes than their rival.

In 1876 Samuel Tilden received more popular votes than Rutherford B. Hayes but Hayes won by one electoral vote due to the Colorado Legislature selecting electors to save money, having only just joined the Union.

In 1988 Democrat Grover Cleveland won more popular votes than Republican Benjamin Harrison but Harrison was able to win the Presidency through the Electoral College. This was due to Cleveland winning heavily in some states and Harrison winning narrowly in others.

However, the issue had remained a purely academic and theoretical possibility for over a century until the 2000 when the election became too close to call and the final tally of Florida became so crucial. It is probably the issue that caused the most anguish amongst commentators because of the simplicity of the argument that the winner should have won.

It appears to European observers as if American democracy is a sham. The most basic rule of democracy is that he who receives the most votes should win. However, it should be remembered that the United States is a federal state and that the founding fathers wished that the President should have broad national support.

The problem of a President being elected with fewer votes than his rival could be avoided through national direct election, but should there be a similarly close contest it could result in a costly and time consuming national recount. Such a situation would make the Florida scenario pale into insignificance.

Malapportionment and Voter Dilution.

It is argued by detractors that the Electoral College system of guaranteeing each state at least 3 electoral votes, thus not being completely proportional, is a malapportionment of representation.

Essentially they believe that the lack of equality of voting power, a dilution of the value of a persons vote, is contrary to the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment., which states:

“…No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any persons of life, liberty, or properly, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws….”

Since the 1960’s state legislatures have been forced to have reasonable equality of representation. (7) In the case of Reynolds v Simms (1964) (8) the Alabama state legislature had its apportionment of districts deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Earl Warren stated:

“To the extent that a citizen’s right to vote is debased, he is that much less a citizen. The fact that an individual lives here or there is not a legitimate reason for overweighting or diluting the efficiency of his vote. The complexions of societies change, often rural in character becomes predominantly urban. Representation schemes once fair and equitable became archaic and outdated. But the basic principle of representative government remains, and must remain, unchanged – the weight of a citizen’s vote cannot be made to depend on where he lives. Population is, of necessity, the starting point for consideration and controlling criteria for judgment in legislative apportionment controversies. A citizen, a qualified voter, is no more no less so because he lives in the city or on the farm. This is the clear and strong command of our Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause. This is an essential part of the concept of a government of laws and not men. This is at the heart of Lincoln’s vision of “government of the people, by the people [and] for the people”….” (9)

It would appear that there could be some argument that the Electoral College does discriminate against people who live in more populous states as their individual votes are not of equal value to those of people in less populous states. However, the above rulings only relate to state legislatures and indeed a strict interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment only declares that states should provide equal protection, and not that the United States should.

It appears therefore that whilst the Electoral College does break the spirit of Equal Protection it does not in fact breach the 14th Amendment.

“Winner Takes All” and The Disenfranchising of Minorities.

One argument put forward against the Electoral College is that it discriminates against minorities. This it is argued is because of the almost universal use of the “Winner Takes All” system of selecting electors. It is clear that a voter who votes for the losing candidate under that system does not have their voice heard. However, Matthew M. Hoffman argues that the “Winner Takes All” system coupled with his assertion that people vote along racial lines (blacks voting for the Democrats and whites predominantly for the Republicans) means that racial minorities do not have their voice heard. He also argues that the unit voting system is illegal under The Voting Rights Act 1965. (10)

However, given that minorities tend to live in the most populous states then they have the ability to swing the vote in these most crucial of states. Therefore, their votes are of great value to candidates who would surely wish to appeal to them. Nonetheless, it is true that literally millions of people in a state can vote for the losing candidate and not receive any representation in the College. Victor Williams and Alison m. MacDonald argue that that is unrepresentative:

“The winner-take-all state unit voting methodology of the electoral college is an inherently unfair and unjust vote weighting system that clearly dilutes the non-majority votes of each state…. [T]he winner-takes-all state unit electoral college voting is an obvious violation of the principle that one persons vote should have the same value as another’s.” (11)

It is often argued that the system depresses voter turnout. It is suggested that in states, which continually return electors from the same party that voter turnout, is depressed because people of a different persuasion do not vote. However, even according to figures compiled by The Center for Voting and Democracy, who are against the Electoral College, Presidential elections consistently attract higher turnouts than Congressional elections. (12) It is therefore suggested that the poor voter turnout figures in the United States are a result of a lack of belief or interest in the political system in general rather than simply being the fault of the Electoral College.

The Contingent Election.

The contingent, election used in cases where no candidate receives a majority of the electoral votes is a much criticised procedure. Opponents of the contingent election argue that it is inherently undemocratic because each state’s congressional delegation has only one vote between them and thus gives a very disproportionate voice to the smaller states. This is undoubtedly the case and is far more disproportionate than the College itself. However, it is all part of the federal nature of the United States and because of the two party system now prevalent in the country it has not been used since 1824.

There can be no doubt that there are some very cogent arguments against the Electoral College which can be summed up in Mr Justice Jackson’s comments in Ray v Blair (1952) (13)

“The demise of the whole electoral system would not impress me as a disaster. At its best it is a mystifying and disturbing factor in presidential elections which may resolve a popular defeat into an electoral victory. At its worst it is open to local corruption and manipulation once so flagrant as to threaten the stability of the country. To abolish it and substitute direct election of the President, so that every vote wherever cast would have equal weight in calculating the result, would seem to me a gain for simplicity and integrity of our governmental process.”

There are however, numerous arguments in favour of the system.

The Advantages of the Electoral College.

Despite, the recent debacle and the democratic arguments used against the Electoral College, the system still has its vociferous advocates whose arguments are a mixture of theoretical and practical positives.

Election Requires a Broad Range of Support.

Proponents of the Electoral College point to the fact that in order to win the

Presidency a candidate must acquire a broad geographical support. The United States of America has a vast geography, with different climates, terrains and cultures. America has large urban areas, industrial towns but also vast agricultural regions. In order to become President, under the Electoral College, it is suggested that a candidate must obtain support from both the urban population centres and the agricultural belt. The winning candidate must thus appeal to more than one section of society or one region of the country in order to obtain election. The President would thus be aware of the issues affecting the whole country and therefore better able to govern the nation as a whole.

John Samples, Director of the Center for Representative Government at the Cato Institute echoes many Electoral College supporters:

“…We must keep in mind the likely effects of direct popular election of the president. We would probably see elections dominated by the most populous regions of the country or by several large metropolitan areas. In the 2000 election, for example, Vice President Gore could have put together a plurality or majority in the Northeast, parts of the Midwest, and California.

The victims in such elections would be those regions too sparsely populated to merit the attention of presidential candidates. Pure democrats would hardly regret that diminished status, but I wonder if a large and diverse nation should write off whole parts of its territory. We should keep in mind the regional conflicts that have plagued large and diverse nations like India, China, and Russia. The Electoral College is a good antidote to the poison of regionalism because it forces presidential candidates to seek support throughout the nation. By making sure no state will be left behind, it provides a measure of coherence in our nation.” (14)

Whilst it is probable that more attention would be given to the most populated areas in a direct election, comparisons with third world and communist or ex-communist countries are alarmist to say the least. It may well be that in the early days of the Union it would have been possible for the country to be split. Indeed this happened with the civil war, but with increased mobility and improved communications the country is effectively a lot smaller and less diverse than it used to be. It is worth noting also that apart from the Native Americans, the population is of fairly recent immigrant descent and thus, regional and ethnic disputes of the nature seen in Russia and India are hardly plausible.

Federalism and The Separation of Powers.

The United States of America is a union of sovereign states and as such has at its core a federal system of government. The Electoral College is a compromise between national and state interests and therefore acts as an important balance. The Electoral College was designed to represent the states’ choice for president. However, it achieves this through the distribution of electoral votes based on representation in congress and thus guarantees a voice for the small states whilst giving weight to the more populous states. It is argued by its supporters that to abolish the Electoral College would be a breach of the crucial balance between state and national government.

As well as being part of the overall federal structure of the union it is also argued that it plays a part in the application of the doctrine of the separation of powers. This is because in the United States the separation of powers is not merely between the executive, legislature and the judiciary but also between the national and state governments. This division acts as a second level of protection against too much power being concentrated in the hands of any one group of people. Its proponents argue that to abolish the Electoral College would simply give the most populous states complete control over the appointment of the Chief Executive of the whole Union, which would give those states undue influence over others, and would be a breach of the very essence of federalism. John C. Eastman of the Claremont Institute states the federalist argument as follows:

“Congress, for example, is divided between two branches, only one of which is apportioned by population while the other, the Senate, is constituted by the distinctly non-majoritarian allotment of seats to States of vastly different populations. This, the founders believed, served to check the raw passions of a majority that might gain sway in the House of Representatives and use its majority power to trample the rights of minorities. And it served to protect the States as a fundamental component of our constitutional system, able to check the power of the national government and thereby help ensure liberty.

The same concern with raw power underlies the constitutional doctrines of enumerated powers, of federalism, of an independent, non-elected judiciary, and yes, of the Electoral College. Indeed, the Electoral College is part and parcel of the entire constitutional structure.” (15)

“In the 2000 election the Green Party candidate Ralph Nader obtained 2.74% of the popular vote and yet received no Electoral College votes. He may well have achieved more popular votes if people actually believed that he could obtain electoral votes”

Political Stability.

Supporters of the Electoral College point to the relative political stability that the United States has enjoyed compared to other “democracies”. They argue that this stability is aided by the Electoral Colleges tendency to exacerbate the two party system. They point to the fact that minor parties have very little chance of obtaining any electoral votes, as a deterrent to extremist parties. They suggest that this leads to interest groups having to bring themselves under the umbrella of one of the major parties. Whilst their views are then heard, they have to abandon their more extreme views and most radical policies in favour of more practical consensual policies. According to the argument, what the United States has in the shape of the Democrats and the Republicans are two practical coalitions, who essentially share the same ideology and aims only differing through methodology. Therefore, the argument goes, the two party system avoids major changes in policy whenever there is a change of government, thus leading to greater continuity.

Whilst it is true that the United States is a relatively stable democracy, the two party system as exacerbated by the Electoral College does however limit voter choice. In effect anyone who does not agree with either of the two major candidates has no way of gaining representation through the ballot box. In the 2000 election the Green Party candidate Ralph Nader obtained 2.74% of the popular vote and yet received no Electoral College votes. He may well have achieved more popular votes if people actually believed that he could obtain electoral votes. It would appear that the political stability, allegedly achieved through the Electoral College, is achieved at the expense of effective electoral choice.

The Electoral College Webzine, a website espousing the benefits of the College states that:

“Whilst the Electoral College tends to produce candidates that look like Tweedledum and Tweedledee, direct election would produce a choice between Pat Buchanan and Pat Robertson or Jesse Ventura and Jesse Jackson.” (16)

Notwithstanding the adversarial nature of some of the aforementioned, it could be argued that at least these characters might raise the level of interest in political life in the United States and lift the poor voter turnout figures.

Minority Interests.

Whilst its detractors argue that the lack of equal protection and the winner takes all system of selecting electors damages minority interests, supporters of the college argue that that very unit voting system actually promotes the interests of minorities.

The Electoral College’s supporters argue that in swing states in which every vote counts, the minority can vote en bloc and therefore increases the importance of their vote. This political leverage means that Presidential candidates have to be receptive to minority views if they want to win such crucial states. If the Electoral College were abolished in favour of direct popular election, then small minorities would be swamped by the majority in a national vote and candidates it is argued would have little to gain from appealing to such groups.

An example of the leverage effect could be that candidates may very well come out with pro-Israel policies in order to win the Jewish vote in a state like New York which has a sizeable Jewish minority. A similar example would be Cuban policy being decided by the need to obtain Hispanic votes in Florida.

This minority bloc voting is further enhanced by the fact that ethnic minorities have tended to congregate in large cities in the most populous states, and therefore they live in the states of greatest electoral vote value and of most interest to presidential candidates. Hence, the Electoral College actually increases the importance of minority views to presidential candidates and thus serves them better than would direct election.

Extensive Recounts.

Following the recounts in Florida which re-ignited the issue of he Electoral College, its supporters have actually turned an apparent negative to a positive in favour of retaining the College. They argue that if the United States were to adopt national direct election that if an election were close that a national recount would be necessary rather than just a state-wide tallying of votes. Such a procedure would be time consuming and extremely costly.

Limits Election Fraud.

It is further argued by supporters of the Electoral College that should the College be abolished in favour of direct election that this would increase the likelihood of fraud. The argument asserts that whilst at present the College states the value of any particular states votes no matter what the turnout, there is no incentive for governing parties in one party states to fraudulently create inflated voting figures as it will have no effect on the overall result. This may be true but in such states as the winner of that states electoral votes can easily be predicted before the election day the system actually disenfranchises supporters of the opposition and would thus restrict participation.

These main arguments in favour of the retention of the Electoral College are well summarised by John C. Eastman:

“The Electoral College does more than just serve as check on tyrannical majority power. It helps channel the popular vote into a constitutional rather than just a numerical, majority, ensuring that the successful candidate has a level of popular support that is dispersed both geographically and ideologically and that, as a result, the electoral winner will be able to govern. The Electoral College also ensure that every region of the country, and indeed every State in every region, has a voice in the election of the President and therefore a part in the successful functioning of the national government.” (17)

It can therefore be seen that there is a real academic, constitutional and political argument over the issue of the Electoral College. Both sides in the debate have cogent arguments in support of their claims. However, the debate need not and is not simply between those in favour of retention or abolition. There is the possibility of reform. In the next chapter I will assess the current proposals for reforming the electoral process, both abolitionist and reforming.

Notes

- 343 US 214 (1952)

- Ibid at 232

- U.S. Electoral College Webzine.

- www.avagara.com/e_c/ec_unfaithful.htm

- CRS REPORT for CONGRESS RL 30804 p9

- 343 US 214 (1952)

- Baker v Carr 369 US 186 (1962)

- 377 US 533 (1964)

- Ibid at p567.

- Hoffman, Matthew M. The Illegitimate President: Minority Vote dilution and the Electoral College. Yale Law Journal Jan 1996 105 n4 p935

- Williams, V. MacDonald, Alison M. Rethinking article II, Section 1 and its Twelfth Amendment Restatement: Challenging Our Nations Malapportioned, Undemocratic Presidential Election Systems. Marquette Law Review Winter 1994 Vol 77 n2 p201 at p249.

- www.fairvote.org/turnout/intturnout.htm

- 343 US 214 (1952) at 234

- Samples, John. “In Defense of the Electoral College.” November 10, 2000 available at www.cato.org/dailys/11-10-00html

- Eastman, John C. “In Defense of the Electoral College” Claremont Institute Center For Constitutional Jurisprudence available at www.claremont.org/publications/eastman001120.cfm

- Electoral College Webzine, www.avagara.com/e_c/ec_directdanger.htm

- Eastman, John C. “ In Defense of the Electoral College” Available at www.claremont.org/publications/eastman001120.cfm

United States Electoral College