In the second part of Dan Heaton’s thesis discussing the United States Electoral College, he looks at the Origins & History of the Electoral College.

CHAPTER 1. ORIGINS & HISTORY OF THE ELECTORAL COLLEGE.

The Presidential Electoral College system is not laid down in any federal statute but is enshrined within the Constitution of the United States of America of 1787. Article II of the Constitution as modified by the 12th Amendment has been in existence as long as the United States itself, and thus in order to examine the origins of the Electoral College it is essential to study how the Constitution of 1787 came into being in the form that it did.

The Road to Philadelphia.

July 4th 1776 saw the Continental Congress issue the Declaration of Independence. The ensuing war evoked nationalist sentiments in American political thought, however, during this period many of the colonies enacted their own constitutions and in effect became states in their own right, with their own governments and thus their own interests to protect. Thus when the great and the good discussed the enacting of the Articles of Confederation the opposing viewpoints of nationalism and localism met head on. In the end the small states with their local interests won the battle as James Wilson a Congressman at the time stated later when addressing the Constitutional Convention in 1787:

“Among the first sentiments expressed in the first Congress, one was that Virginia is no more that Massachusetts is no more that Pennsylvania is no more and Connecticut. We are now one nation of brethren. We must bury all local interests and distinctions. This language continued for some time. The tables at length began to turn. No sooner were the State Governments formed than their jealousy and ambition began to display themselves. Each endevoured to cut a slice from the common loaf; to add to its own morsel, till at length the Confederation became frittered down to the impotent condition in which it now stands. Review the progress of the Articles of Confederation through Congress and compare the first and last draught of it.” (1)

Once the watered down Articles of Confederation had been approved by Congress in 1777 the states had all the rights. The larger states who had previously wanted a strong national Government became more localist in outlook. They had no interest in moving power to the centre as the new Congress was based upon the equal rights of states and could thus be controlled by the smaller less populous states therefore any national power would be of no use to the larger states.

Essentially, in terms of internal affairs, the states acted totally in their own interests and against any notion of the common good, threatening the very existence of the fledgling union itself, Leonard W Levy sums up the situation thus:

“Congress, representing the United States, authorized the creation of the states and ended up, as it had begun, as their creature. It possessed expressly delegated powers with no means of enforcing them. That Congress lacked commerce and tax powers was a serious deficiency, but not nearly as crippling as its lack of sanctions and the failure of the states to abide by the Articles. Congress simply could not make anyone, except soldiers, do anything. It acted on the states, not on people. Only a national government that could execute its laws independently of the states could have survived. The states flouted their constitutional obligations. The Articles obliged the states to “abide by the determinations of the United States, in Congress assembled,” but there was no way to force the states to comply.” (2)

The problems encountered by the Confederation led in September 1786 to a convention in Annapolis, Maryland at which representatives from Virginia, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York agreed that a Constitutional Convention made up of delegates from all the states should meet in Philadelphia in May 1787: “…to take into consideration the situation of the United States, to devise such further provisions as shall appear to them necessary to render the constitution of the federal government adequate to the exigencies of the Union, and to report such an act for that purpose to the United States in Congress assembled….” (3)

Thus delegates from the former colonies met in Philadelphia on may 25th 1787 in order to revise the Articles of Confederation and fashion the Constitution of The United States. Against this backdrop the delegates set about the creation of an independent and permanent executive, the position of President of the United States and a system for appointment to what is now the most powerful political position in the world.

“it was suggested that the states should decide who should be President. However, following the blatant flouting of the Articles of Confederation and the overtly localist tendencies of some of the states, it was feared that this system would allow the President to become the lackey of the states”

The Convention.

In Philadelphia the founding fathers met to revise the constitution, they agreed that there should be a president, but they were undecided as to how this most illustrious position should be filled? The Presidency could not be hereditary as this went totally against the republican form of government envisaged and the anti-monarchist post War of Independence feeling.

There were three main proposals for the appointment procedure. Firstly, it was mooted that Congress should elect the President whether from amongst its own numbers or from elsewhere. This proposal was attacked as it might lead to corruption with the President being beholden to the Congressmen. It was also felt that such a system would cause division in Congress over the selection and that this would be bad for the Union and that such infighting may lead to corruption or political payoffs in order to obtain votes. Just as important at this time though was that such a system allowing Congress to appoint the executive would be an affront to the doctrine of the separation of powers and would have disturbed the balance between the executive and legislative branches of the Government. Thus this suggestion was rejected by the convention.

Secondly, it was suggested that the states should decide who should be President. However, following the blatant flouting of the Articles of Confederation and the overtly localist tendencies of some of the states, it was feared that this system would allow the President to become the lackey of the states and that this would dilute the newly created federation leaving it as impotent as the previous confederation.

The third of the main proposals was that the President should be directly elected by the people of the Union, or at least all those men entitled to vote. However, at the time due to the sheer size of the country and the state of technology during that period it would have been difficult to launch a national campaign accessible to all the people. It was also feared that to do so would favour the most populous states and thus little time would be given by the President to the needs of the people in the smaller less populous states. Given the environment of localism at the time it was also feared that each state would simply vote for their own man the so called “favourite son”, and thus the new head of state would in fact have very little national support at a time when the delegates were looking to create a feeling of a nation rather than fostering allegiance to individual states which could lead to the break up of the Union.

There thus came the great compromise known today as the Electoral College. The College was a compromise between state power and federal authority, between small and large states and according to Victor Williams and Alison M MacDonald (4) a compromise between the northern states and the southern slave owning states.

The Original Design of the Electoral College.

The system laid down Article II of the document which became the Constitution of the United States of America is as follows:

“…Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States shall be appointed an Elector.

The Electors shall meet in their respective States, and vote by Ballot for two persons, of whom one at least shall not be an Inhabitant of the same State with themselves. And they shall make a List of all the Persons voted for, and of the Number of Votes for each; which List they shall sign and certify, and transmit sealed to the President of the Senate. The President of the Senate shall, in the Presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the Certificates, and the votes shall then be counted. The person having the greatest Number of Votes shall be the President, if such Number be a Majority of the whole Number of Electors appointed: and if there be more than one who have such Majority, and have an equal Number of Votes, then the House of Representatives shall immediately chuse by Ballot one of them for President: and if no Person have a Majority, then from the five highest on the List the said House shall in like Manner chuse the President. But in chusing the President, the Votes shall be taken by States, the Representation from each State having one Vote; A quorum for this Purpose shall consist of a Member or Members from two thirds of the States, and a Majority of all the Senates shall be necessary to a Choice. In every Case, after the Choice of the President, the Person having the greatest Number of Votes of the Electors shall be the Vice-President. But if there should remain two or more who have equal Votes, the Senate shall chuse from them by Ballot the Vice-President.”

There are thus three parts to the process; the selection of electors, the process by which electors vote and the contingency election used in situations where no candidate achieves a majority.

Each state is entitled to a number of electors equal to their representation in Congress, Thus, no matter what their population, they are guaranteed at least three electoral votes, two for the two Senators that each state is entitled to under Article I Section 3 of the Constitution and at least one for the one member of the House of Representatives which each state has guaranteed under Article I Section 2. Thus small states gained a proportionally greater representation in the election of the President. Victor Williams and Alison M MacDonald have gone further and assert that the smaller states at this time tended to be the southern slave owning states and that despite their low voting populations for the House of Representatives they benefitted from Article I Section 2 which details how a states representation in congress is to be assessed. Article I Section 2 states that in this calculation “three fifths of all other persons” are to be counted. Thus slaves who had no right to vote could be counted as three fifths of a person thus giving the southern slave owning states a larger proportion of Congressmen than states which only counted free men. With a larger representation in Congress went a larger representation in the Electoral College.

The actual process for choosing electors was left open to the individual state legislatures to decide upon. This was again a compromise between state and federal power. The only prohibition placed on electors was that they could not be Members of Congress or employees of the United States. This was to ensure that the choice of President as the executive branch of government was kept separate from the legislature, and was enacted so as to embody the doctrine of the separation of powers.

Once selected the electors would meet in their own states in order to make corruption more difficult due to the vast geography of the country. The electors would then cast two votes for people they thought fit to be President. In order that the “favourite son” scenario could be avoided, it was enshrined that at least one of the votes cast had to be for someone from another state.

When the voting was completed the votes were sent to Congress were the President of the Senate (a position actually held by the incumbent Vice-President) would declare the results. If one person had a majority of the votes then that person is declared President and the runner up became Vice-President. However, if there was a tie, or if no candidate obtained a majority of the electoral votes then the House of Representatives was to select the President from those with the top five number of votes. This was to be done by the state representation voting as a state not as individual representatives, thus even in the contingency election the smaller states benefit as they become equal to the more populous states each receiving one vote each. Once a President is selected the candidate with the highest number of Electoral College votes would be declared Vice-President, however, should there be a tie then the Senate would vote for the Vice-President.

Alexander Hamilton, writing in the Federalist said of the system: “…[T]hat if the manner of it be not perfect, it is at least excellent. It unites in an eminent degree all the advantages the Union of which was to be wished for.” (5)

Hamilton particularly praised the use of the office of Elector:

“No Senator, representative, or other person holding a place of trust or profit under the United States, can be of the number of the electors. Thus, without corrupting the body of the people, the immediate agents in the election will at least enter upon their task, free from any sinister bias. Their transient existence, and their detached situation, already noticed, afford a satisfactory prospect of their continuing so, to the conclusion of it. The business of corruption, when it is to embrace so considerable a number of men, requires time, as well as means, nor would it be found easy suddenly to embark them dispersed, as they would be over thirteen states,….” (6)

Hamilton also believed that the system would find superior and unifying Presidents rather than merely the favourite son of a populous state:

“This process of election affords a moral certainty that the office of president will seldom fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications. Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity, may alone suffice to elevate a man to the first honours, of a single state; but it will require other talents, and a different kind of merit, to establish him in the esteem and confidence of the whole union, or of so considerable a portion of it, as would be necessary to make him a successful candidate for the distinguished office of President of the United States.” (7)

It was with these persuasive writings from Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay writing under the pseudonym Pubilus in articles collectively known as the Federalist that the argument was waged over ratification of the document drafted at the Philadelphia Convention. The federalists won the day and the Constitution of the United States of America, including the presidential electoral system that has become known as the Electoral College was ratified by the required nine states by June 1788.

“The practice of electors casting two votes for presidential candidates became seen as redundant because the rise of political parties had created what we now know as Presidential and Vice Presidential running mates”

The Early Years of the Constitution.

The early years of the new union saw the rise of political parties. This meant that electors of a given persuasion were likely to give their two electoral votes to like minded individuals thus the likelihood of a tie increased dramatically. This in fact occurred in the 1800 election when electors for the Democratic-Republican party [not the current Republican Party] awarded their votes equally to Aaron Burr and Thomas Jefferson. The decision on who should be President was thus placed in the hands of the House of Representatives, who eventually decided in favour of Thomas Jefferson.

The practice of electors casting two votes for presidential candidates became seen as redundant because the rise of political parties had created what we now know as Presidential and Vice Presidential running mates. The political parties had also started to breakdown the boundaries between state orientated candidates a nd were creating a greater national forum. The election of 1800 was a watershed for the Electoral College. It was its fourth Presidential election and it was to be its last in its present form. The fact that parties had become so prominent in United States politics and that there had been all kinds of political dealings in the House of Representatives in order to get Jefferson elected, including some thirty-six ballots, created the environment from which the 12th Amendment was proposed and ratified.

The 12th Amendment ratified in 1804 stated:

“”The electors shall meet in their respective states and vote by ballot for President and Vice-President, one of whom, at least, shall not be an inhabitant of the same state with themselves, they shall name in their ballots the person voted for as President, and in distinct ballots the person voted for as Vice-President, and they shall make distinct lists of all persons voted for as President, and of all persons voted for as Vice-President, and of the number of votes for each,…. The person having the greatest number of votes for President, shall be the President, if such number be a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed; and if no person have such majority, then from the persons having the highest numbers not exceeding three on the list of those voted for as President, the House of Representatives shall choose immediately, by ballot, the President. But in choosing the President, the votes shall be taken by states, the representation from each state having one vote; a quorum for this purpose shall consist of a member or members from two-thirds of the states, and a majority of all the states shall be necessary to a choice….The person having the greatest number of votes as Vice-President, shall be Vice-President, if such number be a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed, and if no person have a majority, then from the two highest numbers on the list, the Senate shall choose the Vice-President; a quorum for this purpose shall consist of two-thirds of the whole number of Senators, and a majority of the whole number shall be necessary to a choice….”

The 12th Amendment implicitly recognises the prominence of political parties through its requirement that electors vote for separate candidates specifically for the posts of President and Vice President as this facilitates “running mates” to exist and avoids the confusion amongst electors which resulted in the tied election of 1800.

The Amendment also affected the Contingent Election process for the two posts. The procedure by which the House of Representatives selects the President was altered, so that should no candidate receive a majority of the electoral vote the House would now select the President only from those with the three largest number of electoral votes rather than the top five candidates. The Senate was also given the power to select the Vice-President, in cases were no majority of electoral votes exist for that post. They could now select from the top two ranked candidates based on the electoral vote for that position.

Thus, whilst the College system had been altered significantly in the case of voting for separate Presidential and Vice Presidential candidates, the essential formula of votes being split amongst the various states in a somewhat disproportionate manner remained the same. Despite the mood of change the powers that be decided not to overhaul the system and introduce direct election, even though the party system had eroded some of the state allegiances. Tadahisa Kuroda asserts that Thomas Jefferson had previously been an advocate of abolishing the electors and replacing the system with direct election but that he now “chose the option that most advantaged his party, hurt his rivals and simplified the choices to be given to state legislatures.” (8)

“In an attempt to guarantee a Whig Party President, the Whigs nominated three different candidates for separate parts of the country. The Party hoped to use the local candidate’s popularity to obtain an Electoral College majority for the Party and then and only then decide which candidate should be President”

Turbulent Elections.

The elections of 1800 and 2000 are not the only controversial Presidential elections to occur in the history of the electoral college. There have been numerous occasions when the result of an election has been disputed or unusual because of the nuances of the electoral system.

1824.

In 1824 the dominant Democratic-Republican Party had four candidates in; William Crawford, Henry Clay, John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. Andrew Jackson won the electoral vote but was unable to win a majority. The decision was thus passed to the House of Representatives, who under the rules laid down in the 12th Amendment selected John Quincy Adams as President of the United States. This decision was completely within the constitutional remit of the House but not surprisingly caused uproar with Andrew Jackson and his supporters who claimed that the House of Representatives had thwarted the popular will as he had obtained the largest share of the popular vote as well as coming top of the electoral college vote. However, at the time of this election, of the twenty-four states of the Union six did not use popular ballots to appoint electors, with the choice of electors being left to the state legislature. Such states including the populous New York along with South Carolina, Georgia, Vermont, Louisiana and Delaware. New York had 36 electoral votes and South Carolina had 11 but neither of these states sought to know the will of their inhabitants. Thus, the popular will of the people could not be assessed at the time. The election by the contingent process was not unconstitutional but merely highlighted the shortcomings of several states selection policies and was a stepping stone in the democratisation of that process nationally.

1836.

In an attempt to guarantee a Whig Party President, the Whigs nominated three different candidates for separate parts of the country. The Party hoped to use the local candidate’s popularity to obtain an Electoral College majority for the Party and then and only then decide which candidate should be President. However, the plan backfired and the Democratic-Republican Martin Van Buren obtain an Electoral College majority.

1876.

In 1876 the United States was still recovering from the civil war and was entering an economic depression. The country and indeed the political parties were divided over the post-war settlements and tariff policy. This division could not have been better emphasised than in the electoral results of Florida (not for the last time!}, South Carolina and Louisiana. The states were so divided that they all sent two conflicting sets of electoral votes, one set in favour of the Democrat Samuel J. Tilden, the Mayor of New York and one set in favour of the Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes, the Governor of Ohio. In the circumstances Congress set-up an Electoral Commission to decide the outcome of the election in those states. Not surprisingly the Republican Congress awarded the states to Rutherford B. Hayes and he became President.

Whilst most attention with regard to the 1876 election goes to the disputed vote counts in the above states, it is interesting to note the role that Colorado had on the election. The United States Electoral College Webzine makes an interesting point:

“There was also the situation in Colorado where Hayes won with 0 votes.. Colorado was admitted to the Union in August 1876. The state legislature, to save money decided not hold a presidential election…. They simply appointed electors who voted for Hayes. So what put Hayes over the top were 3 electors not by [sic] the public. This was all perfectly constitutional, and did not figure in the controversy over disputed votes.

Was it a coincidence that Colorado was admitted to the Union right before the closest electoral vote in history? Probably not. Colorado was the only state admitted to the Union between 1867 and 1889. The Republican Congress was unwilling to give up the patronage jobs in the territories. So admitting a state to the Union was quite an extraordinary event. Perhaps the expectation of three additional Republican electors was a motivating factor.” (9)

1888.

In 1888 the incumbent President Grover Cleveland of the Democratic Party lost under the Electoral College to Republican Party candidate Benjamin Harrison despite winning the popular vote. By now all states were using popular election to decide upon their electors so it really was a case of the winner of the popular vote losing the electoral vote. According to the Electoral College Webzine (10) Grover Cleveland managed to lose the election by making tariff reform an issue. This made him very popular in the south but lost him votes in the north, thus whilst he won large majorities of the popular vote in the south he lost narrowly in the northern states to Harrison. The election of 1888 is a classic example of the Electoral College working in favour of a candidate with national support rather than one with large support but whose support is regional. Thus, whilst the election result of 1888 has often been used in the past as an example of the flaws of the Electoral College by its opponents, it is also used by its supporters as a sign of the system working as the founding fathers envisaged.

The Electoral College Today.

Allocation of Electoral Vote.

The number of electors allocated to each state is equal to that states representation in Congress, thus it is equal to 2 Senators plus that states number of Representatives which must be at least 1 (Article I US Constitution) The number of electors allocated to each state varies with the changes in their apportionment of Representatives after every decennial census. Whilst the original Constitution allocated each state at least 3 electors, the 23rd Amendment ratified in 1961 awarded 3 electors to the District of Columbia. There are therefore now electors from all 50 states of the Union and the seat of the United States Government. However, American dependencies such as the U. S. Virgin Islands and American Samoa do not receive any electoral votes and so do not play any part in the election of the President.

The Electors.

The vital link between the people and the winning candidate are technically the electors. They are usually loyal local party supporters or activists chosen because they can be trusted to cast their vote for their declared favourite candidate. The process of formal nomination of electors varies from state to state, but they are usually nominated either by the local branch of a political party, by party convention or they are selected by the Presidential and Vice Presidential candidates themselves. The only people prohibited from being electors are members of Congress and employees of the Federal Government. [Article II Section 1 US Constitution.]

Appointment of Electors.

Article II of the Constitution states that “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature may direct, a Number of Electors….” The decision of how to select electors was therefore left to the state legislatures, therefore some legislatures appointed the electors themselves.. However, over the years the states moved towards popular statewide election by ballot. Indeed, since 1836 only South Carolina maintained that policy and they moved to popular ballot following the civil war. The date of appointment which now essentially means Presidential Election Day has now become uniform under federal law. The date for elections being the Tuesday after the first Monday in November in every Presidential Election year. In some states the names actually appear on the ballot paper but in most cases the ballot papers simply read “Electors for…”

Allocation of Electoral Votes.

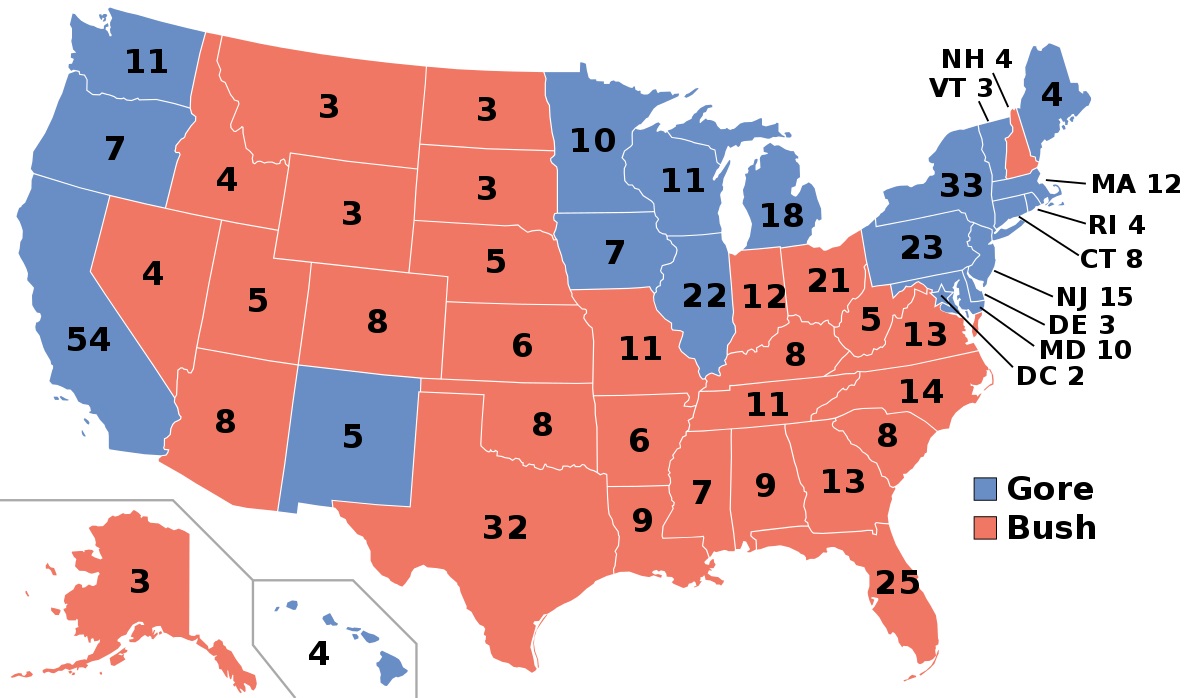

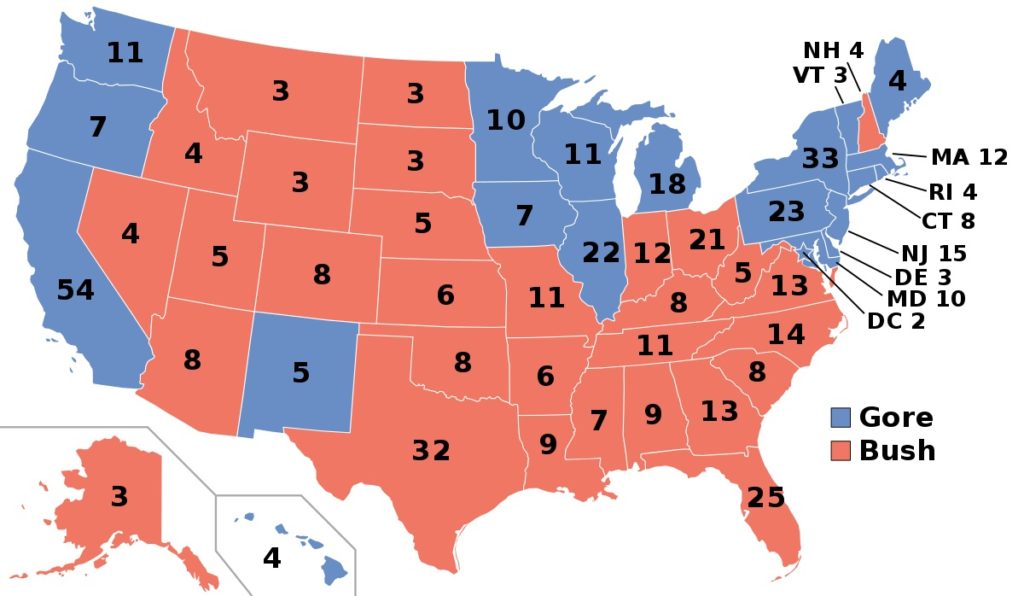

Article II Section 1 of the Constitution states that electors are appointed “…as Legislature thereof may direct…2 and the Supreme Court in the case of McPherson v Blacker (1892) [{1892} 146 US 1] deemed that this power extended to the allocation of electoral votes after any ballot. Through time the system known as “The General Ticket” or “The Winner Takes All” system has developed whereby the candidate who finishes top of the statewide poll receives all of that states allocation of electors. Thus, in Florida in 2000, after the final court ruling, the official result gave George W. Bush 2912790 votes compared to Al Gore’s 2912253, yet George W. Bush was awarded all of Florida’s Electoral College votes. Therefore, with a difference in the Florida poll of just 0.01% George W. Bush was able to become President of the United States. The winner takes all system is used in 48 of the 50 states and in the District of Columbia, however, the states of Maine and Nebraska use what is called the Congressional District method of allocating their electoral vote. This system involves the allocating of the two electors representing the states Senatorial seats to the overall statewide winner, but then allocating the remainder of the electoral votes to the candidates who receive the most votes in the states Congressional Districts. However, given that following the 2000 Census, in the 2004 and 2008 presidential elections, Maine will only have an allocation of 4 Electoral College votes and Nebraska will only have 5, the winner takes all system is by far the most dominant and is a much criticised facet of the modern Electoral College.

Meeting of Electors.

The electors now meet in their state capitals on the Monday following the second Wednesday in December to cat their votes for President and Vice-President.

Counting of the Electoral Votes.

The electoral votes are counted in front of a joint session of Congress on the January 6th following the election, by the President of the Senate who then declares the winners or announces a contingent election.

The system was a controversial compromise at the time of its inception. In the next chapter I examine the arguments against the College and those in favour of its retention. (11)

The founding fathers had to design a system which reflected the federal nature of the new nation and that federal nature still exists today. However, the application of the winner takes all system and the problems with voting machines and counting procedures bring the system into disrepute. Nonetheless the actual Electoral College is a compromise which for the most part has worked well. In the words of Alexander Hamilton:

“[T]hat if the manner of it be not perfect, it is at least excellent.” (12)

Notes

- Farrand, Max editor. Records 1 166-67, The Framing of the Constitution, 1913, New Haven Conn. In Levy, Leonard W. Essays on the Making of the Constitution 2nd edition, 1987 Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Levy, Leonard W. Essays on the Making of the Constitution 2nd edition, 1987, Oxford University Press at pXVII.

- Beloff, Max. Editor. The Federalist 2nd edition, 1987, Basil Blackwell Ltd, Oxford at p463.

- [1] Williams V, MacDonald A, Rethinking Article II Section 1 & Its Twelfth amendment Restatement: Challenging Our Nations Malapportioned, Undemocratic Presidential Election System, Marquette Law Review, Winter 1994 Vol 77 n2 p201-264.

- Beloff, Max editor. The Federalist 2nd Edition, 1987, Basil Blackwell Ltd, Oxford at p348

- Ibid at p369

- Ibid at p350.

- Kuroda, Tadahisa. The Origins of the Twelfth Amendment: The Electoral College in the Early Republic 1787-1804, Contributions in Political Science, Number 344, Westport Conn, Greenwood Publishing 1984 xii 235 as reviewed by Onuf, Peter S, of The University of Virginia Journal of Legal History April 1995 39 n2 p277-278.

- www.avagara.com/e_c/ec_1876.htm.

- www.avagara.com/e_c/ec_1888.htm.

- Farrand, Max editor. Records 1 166-67, The Framing of the Constitution, 1913, New Haven Conn. In Levy, Leonard W. Essays on the Making of the Constitution 2nd edition, 1987 Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Federalist no 64. See Beloff, Max editor. The Federalist 2nd edition. 1987, Basil Blackwell Ltd, Oxford.

United States Electoral College