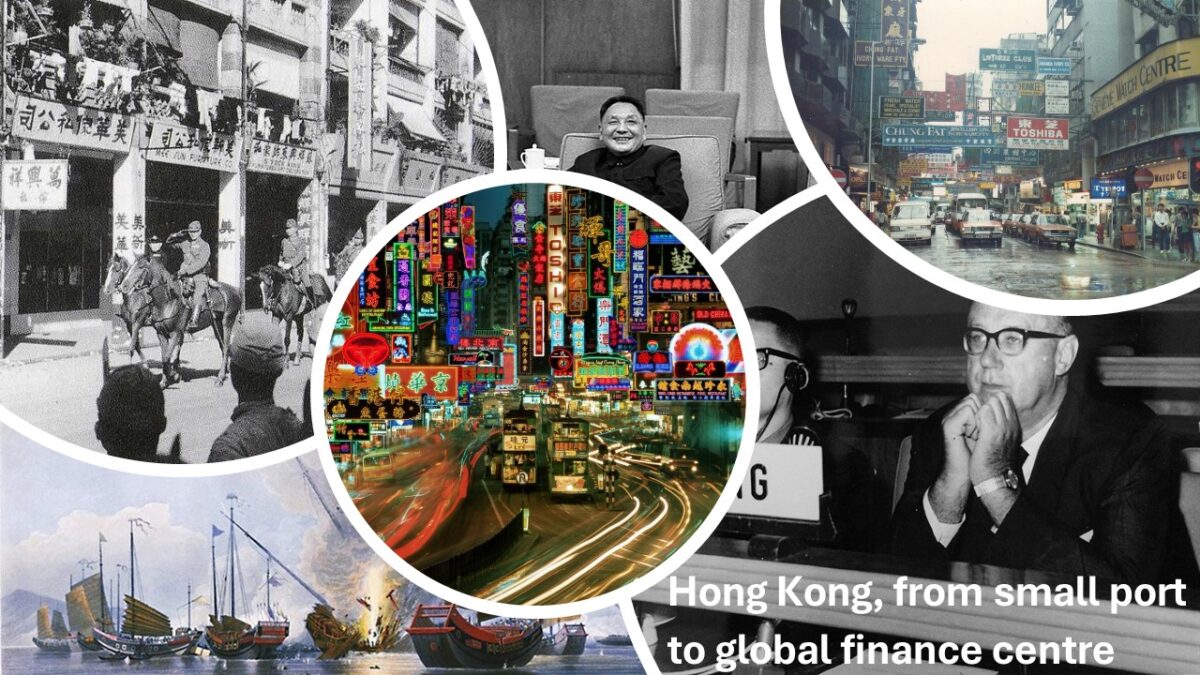

“Hong Kong transformed from a second-rate port city into a global centre of finance and commerce. But how did it achieve this?”

In the 20th century, Hong Kong transformed from a second-rate port city into a global centre of finance and commerce. But how did it achieve this? An overview of the use of ‘positive non-interventionism’, the economic philosophy which powered Hong Kong’s rise to greatness.

Hong Kong Island was ceded to Britain in 1842, in the wake of the First Opium War. Its strategic location was ideal for projecting British military and economic power into south China. At the time, it was home to around 5,000 people, spread across several small fishing villages.

The city grew quickly, powered by trade with China and British financial interests in East Asia. By 1859, the island was home to some 85,000 Chinese residents, alongside 1,600 foreigners. In 1865, the now world-famous HSBC was founded in Hong Kong.

The Kowloon Peninsula was added to the territory in 1860, and the so-called ‘New Territories’ were obtained in 1898 under a 99-year lease. Thanks to the legal and political stability offered by the British, Hong Kong’s role as a trade entrepot continued to grow.

By the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, Hong Kong was central to British interests in East Asia. The territory operated as a free port, with no tariffs on imports, which attracted merchants from China and Europe alike. And then came the Japanese.

In 1941, Hong Kong was occupied by the Japanese after eighteen days of fierce fighting. Japanese occupation was brutal. Civilians were regularly targeted for mass execution, banking assets and factories were seized, and a harsh rationing regime was imposed on the territory.

“he ensured that Hong Kong was granted financial autonomy from the UK, giving HK more freedom to make its own policy. He also resisted calls for a centrally planned industrial strategy”

On August 30th 1945, Hong Kong was liberated, and British control was restored. This is where Hong Kong’s remarkable rise really begins. In 1946, Sir Geoffrey Follows was appointed as the territory’s Financial Secretary and charged with recovering from the occupation.

Follows oversaw a rapid short-term recovery of Hong Kong’s fortunes. In October 1948, he ensured that Hong Kong was granted financial autonomy from the UK, giving HK more freedom to make its own policy. He also resisted calls for a centrally planned industrial strategy.

In 1949, the Communist Party of China emerged victorious from the Chinese Civil War. Capitalists, Chinese nationalists, and political dissidents who feared communist rule fled to Hong Kong. From 1945 to 1951, the territory’s population increased from 600,000 to 2.1 million. Follows’ emphasis on free trade and stability, alongside the cheap labour and expertise of these new migrants, laid the groundwork for Hong Kong’s economic miracle.

What was the ‘positive non-interventionism’ which shaped the approach of the next three Financial Secretaries? In short, ‘positive non-interventionism’ starts from the observation that Government efforts to shape resource allocation are usually damaging to growth, particularly in the private sector.

That’s the ‘non-interventionism’ – but what about the ‘positive’? Successive Hong Kong Governments recognised that the state can take positive steps to ensure improved market function – such as investing in infrastructure, maintaining law and order, and providing legal and political stability. That’s the ‘positive’ part.

“The territory had no income tax, and instead raised revenue through land value capture”

What did this look like in practice?

The territory’s next Financial Secretary was Arthur Grenfell Clarke (1952-61). Clarke refused to introduce regulation of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, and the territory operated without a central bank or monetary policy.

The territory had no income tax, and instead raised revenue through land value capture.

At the same time, Clarke worked with his colleagues in Government to expand Kai Tak Airport, improve the Hong Kong Police Force, and crack down on triad-led gang crime.

“From 1961 to 1971, Government spending as a percentage of GDP fell from 7.5% to 6.5%. At the same time, real wages rose by 50% and acute poverty fell from 50% to 15%”

Yet the real star of the show is John James Cowperthwaite, the city’s Financial Secretary from 1961 to 1971. From 1961 to 1971, Government spending as a percentage of GDP fell from 7.5% to 6.5%. At the same time, real wages rose by 50% and acute poverty fell from 50% to 15%.

Under Cowperthwaite, the territory imposed no controls at all on international capital flows. He refused to collect GDP statistics, fearing that these would only be used to enable economic planning. Taxes were kept low, and Government focused on basic infrastructure delivery.

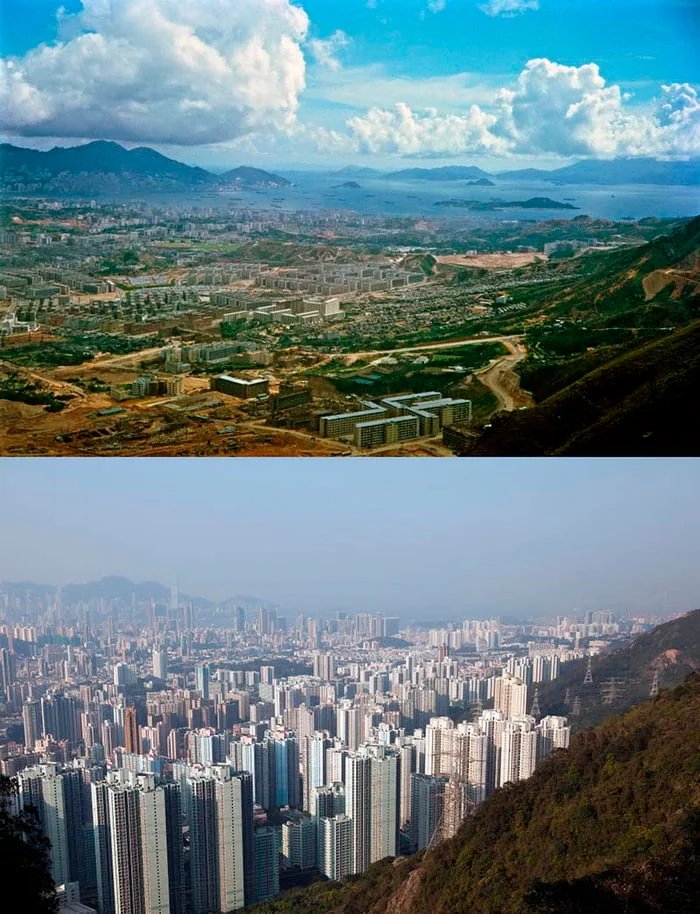

Hong Kong grew rapidly, powered by manufacturing, shipping, finance, and construction. The number of factories in the territory increased from 3,000 to 10,000 over Cowperthwaite’s tenure, while the number of foreign companies registered in HK almost doubled.

This approach was continued by Cowperthwaite’s successor, Philip Haddon-Cave. Indeed, Haddon-Cave coined the term ‘positive non-interventionism’ in 1980. In 1975, Hong Kong emerged as the world’s freest economy, a position that it held continually in 2019.

Haddon-Cave worked with Governor Murray MacLehose to improve services without increasing taxes, tariffs, or regulation. The pair agreed that Government should focus on delivering a few basic services, and should draw on private sector expertise for delivery of major projects.

With this approach, the duo clamped down on corruption and launched the famous Mass Transit Railway. They also managed Hong Kong’s rapid transition from a manufacturing economy to a services economy – prompted, in large part, by a major change just over the border.

In 1978, Chinese premier Deng Xiaoping launched the Open Door Policy, which saw China open up to foreign businesses. In 1980, Deng designated the small city of Shenzhen, just across the border from Hong Kong, as a ‘Special Economic Zone’, in order to encourage foreign trade. Like Hong Kong, Shenzhen would boom in the coming decades.

“Rather than damaging Hong Kong, the growth of cheap manufacturing in China allowed the territory to transform into a hub for financial and legal services”

In the 1980s, its growth was powered by manufacturing. The city’s low labour costs and high regulatory flexibility made it attractive for businesses looking to reduce their costs – including firms in Hong Kong.

Rather than damaging Hong Kong, the growth of cheap manufacturing in China allowed the territory to transform into a hub for financial and legal services, with immediate access to cheap goods and cheap labour from China. Costs remained low and growth remained steady.

“Hong Kong’s remarkable growth continued throughout the 1980s and 1990s, guided by positive non-interventionism”

For those wanting to access the lucrative Chinese market, Hong Kong was a perfect entry-point. The stability of Britain’s common law system and HK’s light touch regulation gave foreign businesses confidence that their investments would be protected.

Hong Kong’s remarkable growth continued throughout the 1980s and 1990s, guided by positive non-interventionism. In 1997, HK was returned to China, after more than 150 years of British rule. Nevertheless, positive non-interventionism has continued to shape HK’s economic policies.

Though HK faces challenges today, it continues to stand as a global hub for financial and legal services. Its remarkable story is testament to the power of free markets – but also to the importance of limited, effective government which focuses on stability and order.

Reproduced with kind permission of Sam Bidwell, Director of the Next Generation Centre at the Adam Smith Institute, Associate Fellow at the Henry Jackson Society, although views are his own. Sam can be found on X/Twitter, on Substack, and can be contacted at s.bidwell.gb@gmail.com. This article was originally published as a X/Twitter Thread at https://x.com/sam_bidwell/status/1817279031345352801