Reforming Healthcare against NHS Propaganda

Economic Piece by Josh L. Ascough

No subject could be more controversial to discuss in the UK more than reforming; or abolishing the NHS. The NHS has existed for over 70 years, and over that time the British people have insisted in telling themselves that, they have ‘the best healthcare system’, and that the NHS is ‘the envy of the world’.

The only problem is…none of this is even close to being true.

“The idea that the organised working classes were demanding a government takeover of healthcare is a post-hoc rationalisation, which projects the fondness for the NHS, which the public subsequently developed, back into the period of its creation”

We continue to tell ourselves that the NHS was the great achievement of the working classes; rising up and demanding national healthcare, in which free access would give power to the people. But, as Kristian Niemietz of the Institute of Economic Affairs points out:

“The creation of the NHS had little to do with pressure from below; it was not a change that ordinary people had fought for. Far from being People Power in action, the NHS was a brainchild of social elites, to which the general public just passively acquiesced. The idea that the organised working classes were demanding a government takeover of healthcare is a post-hoc rationalisation, which projects the fondness for the NHS, which the public subsequently developed, back into the period of its creation.” (Kristian Niemietz. Universal Healthcare Without the NHS. p. 19)

Nick Hayes has reiterated this ex-post rationalisation; explaining that huge support for a nationalised health system was merely a pipe dream piece of propaganda:

“The evidence before us seems to indicate a fairly large amount of resistance to State interference in the field of medicine […] roughly half the population was opposed to any major change on the health front, a quarter disinterested and a quarter in favour of State intervention.” (Nick Hayes. English Historical Review. p. 659)

Evidence in our modern times, gives an interesting expansion on this. The British Social Attitudes Survey (2015) reveals when members of the public, are asked if they would hold a preference for being treated by an NHS-based provider of healthcare, a private profit driven, or a private non-profit provider, 43% state no general preference. A further 18% provide an explicit preference for independent, non-state-based providers of healthcare.

The phony info from NHS propagandists’ continues. The system prior to the creation of the NHS was not a bleak world where people died in the streets; desperately searching for a doctor only to find none exist. Before 1948, the health system operating in the UK was well developed. The system was rooted in the mutualism of the 19th century. The creation of the NHS was not the development of a new system; it was simply a government takeover.

Let’s get back to the common phrase mentioned earlier: the NHS is the envy of the world. The argument is that the NHS is the envy of the world, due to instituting a system, which does not base its service on an individual’s ability to pay for said service. This is treated as an outstanding achievement, yet the vast majority of the developed world has universal access to healthcare (the US is the exception, but we will come to that later). Are we not begging the question of how the NHS is the envy of the world, when the reality of the developed world’s health systems indicates otherwise? Your neighbour can hardly envy you for what you have, if he already has it.

“if the NHS is the envy of the world, then why is it, after over 70 years no developed nation has copied the structure the UK has; why does it refuse to copy the system it apparently envies so much?”

Furthermore, if the NHS is the envy of the world, then why is it, after over 70 years no developed nation has copied the structure the UK has; why does it refuse to copy the system it apparently envies so much? The answer comes in two:

(1) Other developed nations understand there is a difference between universal access as a standard, and the nationalisation of healthcare.

(2) The NHS is not the envy of the world; nor has it ever been.

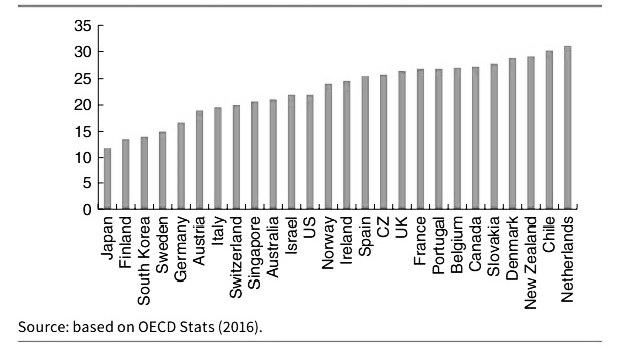

The NHS is not just far from the envy of the world when looking at the universal healthcare status of other developed nations, but according to the OECD, the UK has one of the worst healthcare systems within the developed world. When the report was first published, The Independent stated:

“The quality of care in the UK is “poor to mediocre” across several key health areas […] and the NHS struggles to get even the “basics” right […] Britain was placed on a par with Chile and Poland.”

The Financial Times in addition reported on the findings; stating the following:

“Britons are less likely to survive a heart attack, stroke and leading cancers than people in many other developed nations, according to an assessment of international health systems”

Many apologists for the NHS, would be quick to point to the Commonwealth Fund Study; proclaiming that the CFS “proved” that the NHS is the best system in the world, because it was ranked 1st.

This completely ignores that the CFS looked at inputs, not outcomes. When it came to the one category which looked at outcomes, the UK came out second to last, only slightly above the US. In addition the Commonwealth Fund Study was designed to systematically favour healthcare systems which are tax-funded. The CFS asked patients if their insurer ever declined payment for treatment, and whether they have ever incurred out of pocket payments in excess of over £1,000. These declining of payments and out of pocket payments, would not only be almost impossible under the NHS, but under the systems of Sweden and Norway also. Looking to the CFS for neutrality is like looking to the Central Bank of England for financial stability; you have to lie and make assumptions that fit the outcome you want. The CFS held a category for cost issues titled ‘Cost-Related Access Problems’; this however is based on price limitations with regards to consumers, and mentions nothing on the matter of non-cost based restrictions, such as state rationing.

Many proponents of the current system, when presented with this information, would be quick to state: “okay sure, the NHS has some problems, but that’s just because of underfunding and the spending being cut.”

“In 2018, spending on the NHS was £214 billion; an increase in spending of 296% over a 20 year period. If there has been a cut in spending on the NHS, I’m failing to see where it is”

Well, reality paints a different picture.

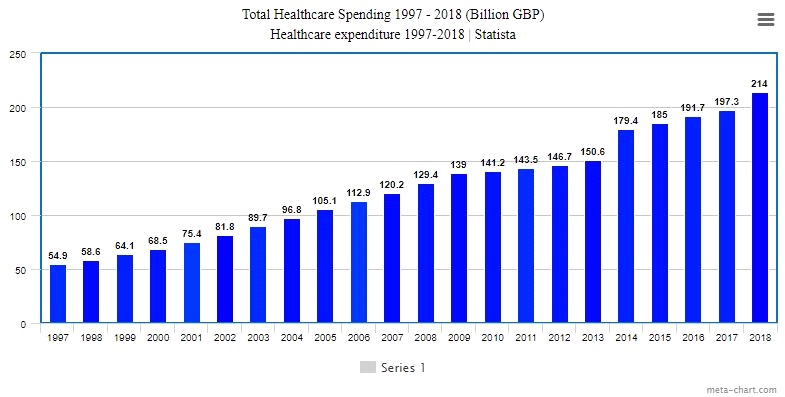

According to data from Statista, from the period of 1997 to 2018, spending on the NHS has been on a continuous increase, as shown below:

As shown in the data, in 1997, spending on the NHS was at roughly £54.9 billion, and has been on a consistent rise. In 2018, spending on the NHS was £214 billion; an increase in spending of 296% over a 20 year period. If there has been a cut in spending on the NHS, I’m failing to see where it is.

Before we touch on the US healthcare system, and the myth of it being a free market system, I think the reader would agree it is important to “put my money where my mouth is”, and provide examples of how the NHS fares compared to other developed nations.

The next few sections will look at the following:

- NHS Outcomes Compared to Other Developed Nations.

- The Universal Systems of Other Developed Nations

After we’ve discussed the US healthcare system, we will go over potential reforms and alternative means of providing healthcare, while keeping the essence of universality.

NHS Outcomes Compared to Other Developed Nations

Let’s take a look at performance rates of the NHS and other systems.

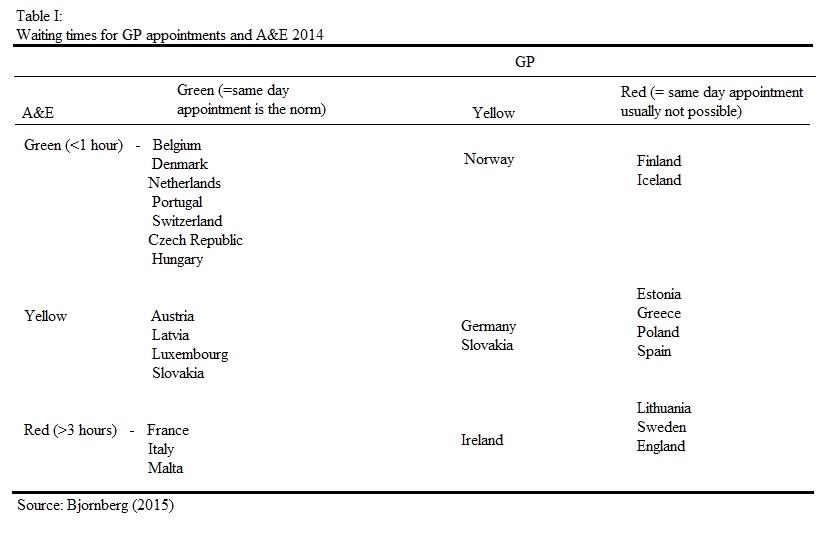

The above table showcases how countries’ healthcare systems compare when it comes to waiting times for GP appointments and A&E.

Nations marked as green indicate an average waiting time of less than 1 hour, yellow in between 1 – 3 hours, and red over 3 hours.

As we can see, the top performers are Belgium, Denmark, Portugal, Switzerland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary. The worst performers include Lithuania, Sweden, and England. Under the NHS, obtaining a same day appointment to see a GP is close to impossible, and waiting times in A&E on average are over 3 hours.

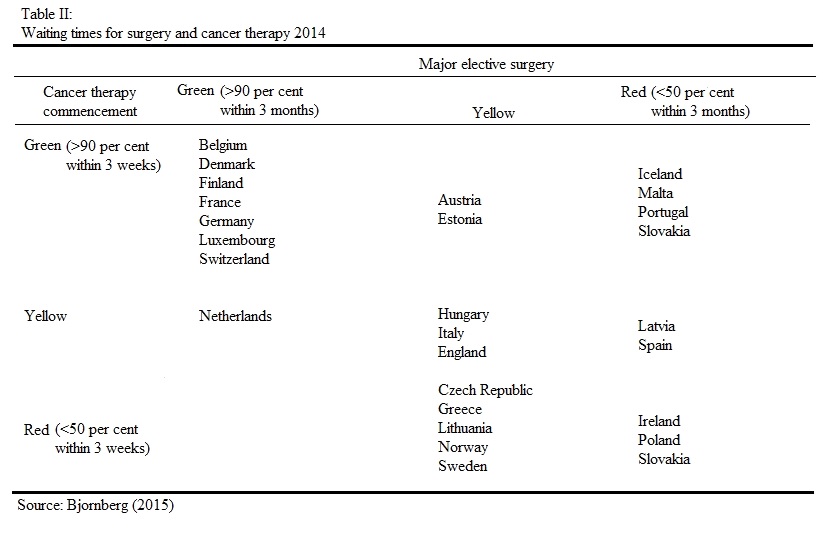

In the second table we look at the waiting times for surgeries and cancer therapies. The top performers here are: Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany and others. The worst performers include Ireland, Poland, and Slovakia. The NHS rates yellow, meaning roughly 50% can be conducted within 3 months.

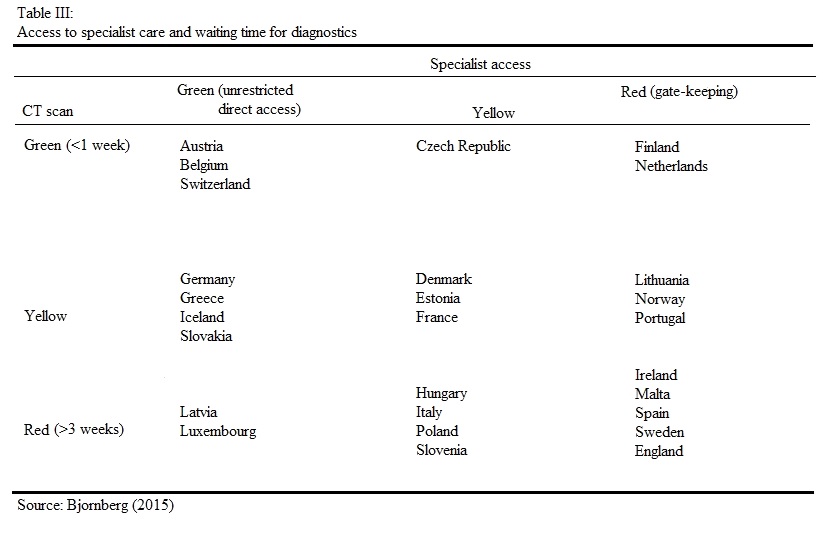

The third table looks at the waiting time for diagnostics, and how easy it is to receive specialist care; if a patient can access such care directly, or if there is gate-keeping in place such as going through a GP.

The top systems in this regard are Austria, Belgium and Switzerland. The longest waiting times for diagnostics and restrictions in place for accessing specialist care occur in Ireland, Malta, Spain, Sweden and England.

Throughout all of these areas, many systems dip between green and yellow, some more than others consistently keeping in the green. The NHS on the other hand, the majority of the time remains in the red, with only one example of being in the middle (yellow).

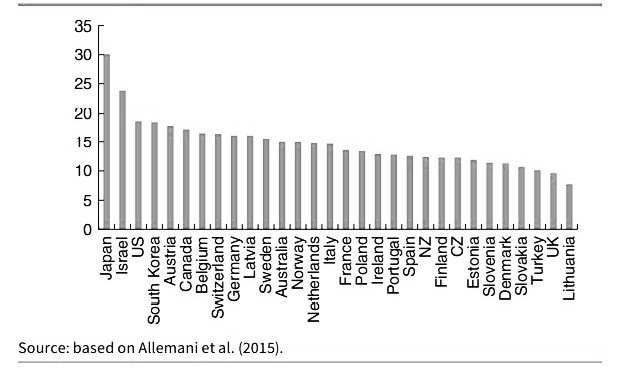

We’ve taken a look at waiting times, what about survival rates? Let’s take a look at cancers first.

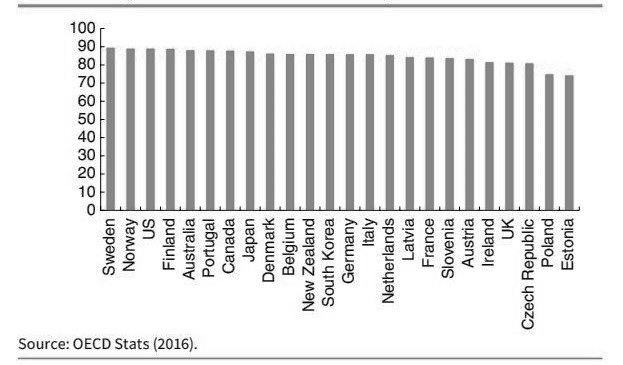

In the UK the most common form of cancer is breast cancer. The diagram above shows the 5 year survival rate for breast cancer patients. The UK’s survival rate is 81.1%; roughly 5% behind South Korea, and roughly 2% behind Austria; if NHS patients had been treated under the South Korean system, we can speculate roughly 2,500 lives could have been saved, and extended every year.

The second diagram shows the five year survival rate for prostate cancer. Under the NHS system, the survival rate is 83%, which is lower than most of the developed world. For patients in Sweden which ranks 12th in the diagram, the survival rate is roughly 6% higher. We can estimate that if NHS patients were treated there, a further 2,800 could have survived.

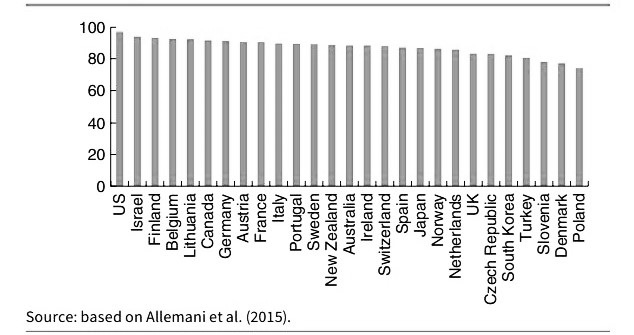

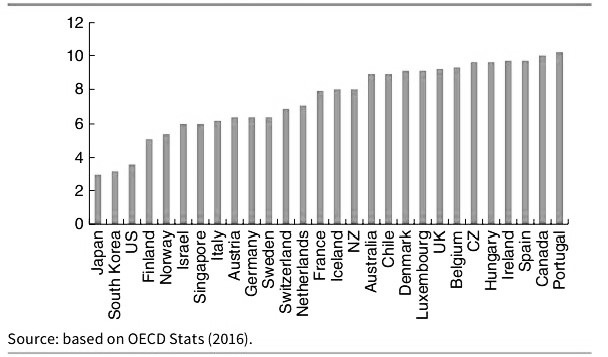

Lung cancer is next on the list. The UK has a survival rate of less than 10%, making it the worst performing compared to all high income, developed nations. Roughly 2,400 additional lives could have been saved under the Australian system, which is 5% higher than the UK.

Let us take a look at stroke mortality rates:

Ischaemic strokes are one of the most common types of stroke in the UK, with roughly 150,000 cases per year (Stroke Association 2016). The UK has a survival rate of 9%. Again, if NHS patients were treated in Sweden, around 3,000 extra lives could have survived an Ischaemic stroke.

Finally, we look at the mortality rate for Haemorrhagic strokes. The UK, once again, is a poor performer for survival. The UK has a mortality rate of 26.5%, which is over 4% higher than the US; translating to roughly 1,000 excess deaths.

“The systems of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany and Belgium, can be described under a broad term of operating under Social Health Insurance systems. In the rankings previously shown, these countries have consistently outperformed the NHS”

The Universal Systems of Other Developed Nations

We’ve looked at survival rates and mortality under the NHS system, and so we shall now go over what the universal character of other developed nations looks like.

The systems of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany and Belgium, can be described under a broad term of operating under Social Health Insurance systems. In the rankings previously shown, these countries have consistently outperformed the NHS.

How Does Social Health Insurance Work?

Social Health Insurance works a similar way to standard insurance. There are however a few unique qualities which are:

- Community Rating: Under a SHI system, insurance companies cannot raise premiums based on an individual’s health risks.

- Obligation to Accept: SHI systems prohibit insurers from rejecting coverage based on an individual’s medical history.

- No Exclusion: Pre-existing conditions cannot be denied for coverage under a system of SHI.

- Individual Mandate: Under a SHI system, it is compulsory for all individuals to purchase SHI, and is mandated by the state. If an individual does not purchase SHI, then they are put on one automatically; even against their will.

- Premium Subsidies: Due to the point of mandates, the government subsidises the SHI of people on low incomes. For some nations this is a means-tested based subsidy, in others it is income dependent.

Under the Swiss system of SHI, it could be argued there is a higher degree of freedom of choice for patients than in other SHI systems, including a cost-sharing measure worth looking into. Out-of-pocket payments under the Swiss SHI, account for roughly a quarter of total healthcare spending (according to W.H.O 2015: 132-133). This system has two distinct components: deductible and proportional co-payments. Deductible works similar to most insurance systems with excess; there is a minimum cost threshold which, once costs exceed this, the insurance covers the excess costs. People can freely have a higher minimum threshold set, in return for premium rebates.

Co-Payments are capped at a certain amount per year. Once a patient’s collective medical bills reach said amount, then they face no further expenses.

“In order to prevent the cost of healthcare rising exponentially during old age, German PKV insurers are required to smooth premiums over people’s lifetime. This “pre-funding” mechanism works in a similar way to a pension”

The German health system has two types of healthcare coverage. These are the standard type of Social Health Insurance; known as GKV, with the community rated premiums and other qualities mentioned above, and a conventional, private health insurance; known as PKV, with varying premiums, and no risk compensation.

Additionally, the German system has a quality that many nations could learn from: an accumulation of old-age reserves. We understand that healthcare costs are flat for the majority of life (not including exceptions), and then rise with age. In order to prevent the cost of healthcare rising exponentially during old age, German PKV insurers are required to smooth premiums over people’s lifetime. This “pre-funding” mechanism works in a similar way to a pension; insurance companies build up an old-age fund on behalf of their clients during their working life, and later draw on this fund for care during old age.

Before we go into the US, I want to briefly talk about the South Korean system.

South Korea has a universal health insurance system, similar to that of SHI; the difference being though, is that the state is unable to set market prices. Many Koreans seek additional private coverage due to the state-based insurance being insufficient to cover all the costs; around 8 out of 10 Koreans take out private coverage, with an average cost of 120,000 Won (£75) a month.

Care in South Korea is provided by hospitals which are 94% private, a fee-for-service model and no direct subsidies. This private system is not purely for-profit, the Korean system has a mix between for-profit, non-profit and charity foundations. The presence of private hospitals expanded in the early 2000s; from 2002 to 2012, private hospitals rose from 1,185 to 3,048. Further information on the South Korean system with a comparison to Italy, and a look at how it handled the outbreak of Covid-19, can be found here:

- https://mises.org/wire/markets-vs-socialism-why-south-korean-healthcare-outperforming-italy-covid-19

- https://www.bma.org.uk/news-and-opinion/prepared-for-the-worst-how-south-korea-fought-off-covid-19

The USA: Free Market Healthcare?

Most of the time NHS propagandists will point to the US and decree: “See! That’s free market healthcare for you! If we didn’t have the NHS (praise be upon it) then we’d have a US system!”

There are two problems. firstly, NHS propagandists intentionally ignore the vast majority of other SHI systems which outperform the UK; relying on the publics ignorance of other systems outside the UK and US. Secondly, the US has not had anything close to a free market in healthcare for at least 100 years. It has become an interventionist, heavily regulated system with positions on competition similar to that (which I’ve discussed a fair number of times) of Neo-Classical General Equilibrium Theory and Perfect Competition. I won’t go into the subject in order to save the reader time, but if you’re interested in understanding what I’m referring to, you can check out my article where I discuss it in detail here – https://croydonconstitutionalists.uk/marshallian-curve/

As was mentioned above, the United States has not held a free market in healthcare since 100 years ago. Jacob Hornberger, the founder and president of the Future of Freedom Foundation, gives a mention to this in his book, The Dangers of Socialized Medicine:

“For over one hundred years, the American people said no to governmental intervention into health care. Americans did not permit their respective states to licence physicians and other health-care providers. They did not permit government to provide health care to the poor and needy. No one was required to purchase health insurance.” (Jacob Hornberger. The Dangers of Socialized Medicine. p. 15)

The government has always attempted to interfere in healthcare, including various lobby groups and unions wishing to curtail care with the use of government power, however it could be argued the defining moment American healthcare changed for the worst forever was the successful lobbying done by the American Medical Association. To further quote Mr Hornberger, he goes into great detail on the impact the AMA had on healthcare in the US:

“The American Medical Association is perhaps the strongest trade union in the United States. The essence of the power of a trade union is its power to restrict the number who may engage in a particular occupation. This restriction may be exercised indirectly by being able to enforce a wage rate higher than would otherwise prevail. If such a wage rate can be enforced, it will reduce the number of people who can get jobs and thus indirectly the number of people pursuing the occupation. This technique of restriction has disadvantages. There is always a dissatisfied fringe of people who are trying to get into the occupation. A trade union is much better off if it can limit directly the number of people who enter the occupation-who ever try to get jobs in it. The disgruntled and dissatisfied are excluded at the outset, and the union does not have to worry about them” (Jacob Hornberger. The Dangers of Socialized Medicine. p. 65)

“the number of medical schools in the US, from the period of 1910 to 1920 dropped from 131 to 85. This cut in medical schools not only had; and continues to have, a supply-side effect by causing prices to artificially be forced up”

The AMA’s successful lobbying campaign, was to restrict the number of doctors who could enter the medical profession by drastically reducing the number of medical schools in the country, and enforcing mandatory licencing into the nation. After the successful lobbying for accreditation was granted, the number of medical schools in the US, from the period of 1910 to 1920 dropped from 131 to 85. This cut in medical schools not only had; and continues to have, a supply-side effect by causing prices to artificially be forced up, it had a huge impact on women and African Americans entering the medical profession. By the time of 1944, the total number of medical schools which admitted black people was cut from 7 to 2.

Many may argue that licencing is good particularly for healthcare. But a licence does nothing to prove a doctor is competent. A doctor could have been in the medical profession for 30 years and be completely incompetent. Two types of objections can be made against licencing:

Economic Objections | Licencing puts a gap between patients and healthcare providers. By restricting the trade of healthcare through additional costs for licencing, it reduces the supply; by reducing the supply this, as stated previously, artificially forces the price up. This added cost is passed on to the consumers of healthcare services. This barrier to entry goes completely against the freedom of entry required for a competitive market to function, under entrepreneurial discovery.

Social Objections | Licencing gives a false sense of security to patients that lead to unfulfilled expectations of doctors being medical automatons; incapable of making human errors and bringing nothing but unnatural perfection to the table. This can harm the relationship between the doctor and patient; causing high dependency and resentment. Furthermore licencing as indicated above, discriminates against not only African Americans and women, but poor people too. While it has been used to keep women and minorities out of the medical profession in the past, the continued effect it has on the poor, is to force them out of the market through disincentives; via expensive education and other requirements for licencing.

Licencing, to some up, is designed to keep doctors free from competition, and increase their wages, through the means of the government giving out privileges and putting up barriers to entry. It is a throwback to the old, European Guild system, and has made the healthcare market aristocratic.

To quote Hornberger once more:

“Licencing is a special-interest legislation for the benefit of physicians and other medical personnel. Its primary purpose and effect are to limit entry into the medical profession in order to protect medical people from competition. Does licencing ensure competent doctors and nurses? If it does, then why do we continue to have so many malpractice judgments against doctors and other medical personnel? And one problem with licencing is that it seduces the public into believing that because a person has been licenced by the state, he must be competent. What would happen if licencing were repealed? Well, no one would run out into the street looking for a quack to perform heart surgery on him. […] What if someone needed a new doctor? The likelihood is the person would rely on the recommendation of his current physician. Moreover, well-established and well-known physicians in the community would band together to publish a list of recommended doctors in the area; private certifying agencies (i.e., Consumer Reports or Good Housekeeping) would do the same.” (Jacob Hornberger. The Dangers of Socialized Medicine. p. 22)

“the government pays for roughly half of all healthcare purchased in the US. Since Medicare and Medicaid patients pay little or nothing, it creates an incentive to consume more than one would value if they incurred the costs”

Medicare and Medicaid

What are the interventionist effects of Medicare and Medicaid? Aside from the extortion of resources, the two forms of medical welfare have negative effects on the demand-side of the equation.

The way it is affected is, the government pays for roughly half of all healthcare purchased in the US. Since Medicare and Medicaid patients pay little or nothing, it creates an incentive to consume more than one would value if they incurred the costs, which if the costs were internalised, it would create incentives to shop around for care. Up until the 1980s, Medicare and Medicaid reimbursed providers, meaning neither patient nor doctor had any incentive to keep either costs down. This lead to a sharp upward movement in prices for insurance and healthcare in general. As a result, many people and small businesses were and are, priced out of the insurance market.

The FDA, patents and insurance regulations also play a huge role in the high expense American’s pay for healthcare.

Insurance

Employer-Provided Health Insurance (1943) – While not mandatory in all states, Employer-Provided Health Insurance requires an employer to pay for the coverage of their employees. Since the individual patient is not facing the costs of said coverage, this leads to people not being as fiscally responsible as they would be; leading to higher risks and higher costs. This also plays a role in why low-pay workers find it hard to leave their job; if they did they would be at risk of not being covered should they face medical needs, leading to employees in states where it is mandatory being dependent on their employer.

Mandated Coverage – The state of California since 2011 has made it mandatory for insurance providers to cover maternity leave (legislation SB 299, AB 592, SB 222 and AB210) This means that even if a woman does not want children, or cannot have children for medical reasons; or because of age, she still has to pay for the coverage of something she will either never want, or never be able to have. This waste not only affects the insurer, but the policy holder, by forcing them to pay a higher price.

Mandatory Insurance – The Obamacare Individual Mandate, made it mandatory on the federal level for all American’s to purchase health insurance. This has the obvious effect of artificially forcing up the quantities being purchased and the demand, leading to higher prices for insurance and medical care. As of 2019 the mandate was no longer required on the federal level, however at least 5 states and the District of Columbia have maintained the mandate for purchasing health insurance.

FDA

Slow-Testing and Approval Process – The FDA’s process of approval times and testing has gone through a very regressive motion. Before 1962 the FDA was required to approve a drug within 180 days unless the new drug was proved to not be safe; meaning there was a time constraint on the FDA, and new drugs could get into the medical market faster. After 1962, said time constraint was removed, and since then the drug approval process has lengthened exponentially. To give a bit of context, prior to 1962 the time between filing and approval was an average of 7 months, after 1967 that time rose to 30 months, and by the late 1980s the time between filing and approval shot up to 8 – 10 years. This excessively lengthened process has seen the cost of testing new drugs rise to around $800 million per drug, and due to the lack of viable substitutes for patients has caused the price of drugs already on the market to rise.

Anti-Advertisement – Advertisement of approved drugs for newly discovered uses, which may be more beneficial than it’s conventional use, is prohibited under FDA rules. This leads to many companies not finding it worthwhile to re-evaluate an approved drug for alternative uses. This restriction has created a barrier to entry in the drug market; not only blocking entrepreneurial innovators from advertising their discoveries, in the attempt to alert consumers of what they may hold an absence of information over, but is designed to protect already existing drug companies from competition.

Patents

IP the Restrictor of Competition

IP is designed to protect the producer of a drug from competitors who wish to reverse engineer their drug, in order to sell similar drugs on the market. IP is not simply the protection of a brand, it restricts who can produce and sell what. It is IP which has led to the rising costs of epipens and insulin. An example of drugs without IP and drugs with, are painkillers and Epipens. In 2020 the average cost of a two-pack of Epipens was $699.82. Pain Relievers with no IP can be purchased at a low price of $3.88 for a 24 pack. If IP was removed from all drugs and reverse engineering by competitors was allowed, dominant drug companies would have to find new ways to innovate their drugs, lower their prices to withhold and stall competition, or be priced out of the drug market.

“Mandates and freedom are opposites. If a person is free, then that means he is not mandated to buy anything. If a person is mandated to buy something, then he is not free. Mandates are not a free-market alternative, because mandates violate free-market principles.” (Jacob Hornberger. The Dangers of Socialized Medicine. p. 14)

“Private doesn’t simply mean “for-profit”, private means there is no government intervention, micro-management, protections, controls or ownerships”

An Alternative to the NHS

Keeping in mind everything we’ve gone over, is it possible to have universal access to healthcare within a free market in healthcare? Yes; if you allow for variety in the means of acquiring medical care, and the ways to provide it.

What do I mean by this? Private doesn’t simply mean “for-profit”, private means there is no government intervention, micro-management, protections, controls or ownerships.

Assuming the reader understands how a for-profit provider would operate (like any other service provider), in order to save time we’ll simply look at what alternatives could exist alongside for-profit providers.

Limited Local Government Display

The British people are a very charitable people, and Britain has had a culture that values empathy and charity for centuries. The difficulty that comes with seeking help, is an absence of information, with regards to the existence of charities that can help people. Local councils can play a very limited role, in advertising all health-based charities that operate within their borough, or that operate nationwide, but which have easy access facilities within the borough. These advertisements could be in the form of notice boards in the council buildings, as well as mailing lists to communities the councils’ understand to have poor demographics.

This would not only expose large numbers of charities to potential donors who did not know these charities existed, but also to the poor who may not know where or who they can turn to.

To put my thoughts into actions, I recommend donating to BenendenHealth. They are a non-profit, affordable care provider that was established in 1905, with the purpose of joining people together to help with medical care when they need it. You can make a donation at https://www.benenden.co.uk/about-benenden/charitable-trust/donations/

Subscription Institutions

This one may seem a bit strange to the reader, so I’ll need to take some time to explain what I mean. The Subscription Institution proposal I’m making, is based on the structure and methods of provision of the Mises Institute. The Mises Institute is a non-profit organisation dedicated to spreading the economic theories of the Austrian School.

The Mises Institute, generates its funds via donations, but also raises funds through a subscription basis; where subscribers pay a monthly fee, and receive benefits such as discounts, newsletters, magazines, and updates on events for members. An additional means of raising funds is by selling products both to members and non-members. As of late, due to charitable donations the institute has begun its own Master Degree in Economics for a lower price than other universities; the average cost for a Masters course ranges from $20,000 – $60,000, whereas the Mises Institute charges around $4,000.

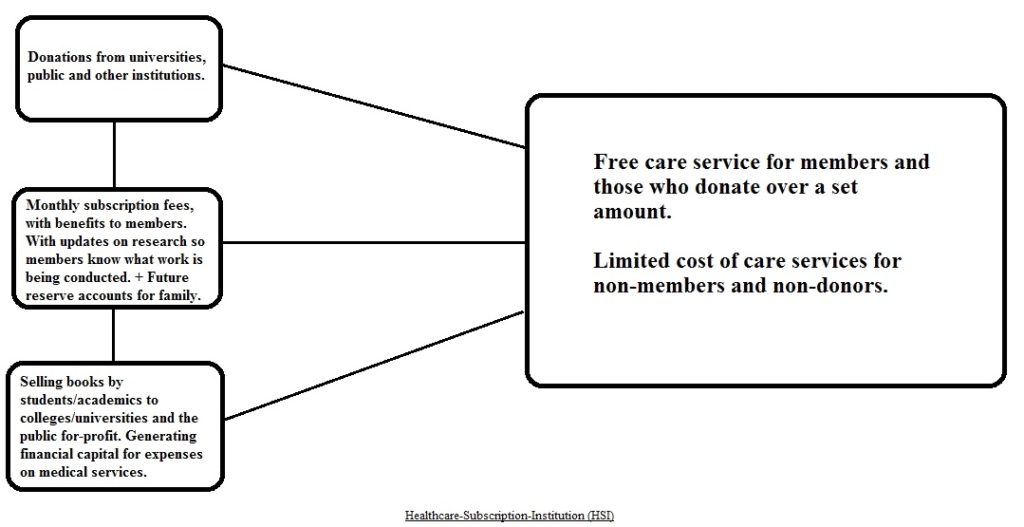

A similar format could be imagined for private, subscription-based healthcare institutions. We can refer to these as Healthcare-Subscription-Institutions (HSI).

Above we see a basic outline of how such an institution could function. They would receive donations from members of the public on a voluntary basis, as well as universities and other institutions who would mutually benefit from research being conducted.

Secondly, the option of a monthly subscription, would allow members of the public to receive certain benefits; such as free care services, newsletters on developments and research being conducted with/without collaboration with other institutions, and discounts on products such as books, human anatomy models, and health conferences.

Thirdly, the Healthcare-Subscription-Institution (HSI) would generate additional financial capital by selling books by academics, doctors and recently graduated students. This would benefit the producers of these books by expanding the access to their work, as well as assisting to build up a resume for recently graduated students.

Finally, Future-Reserve-Accounts would allow individuals to set up what could be likened to a savings account for their children or grandchildren. They would pay a monthly deposit, to which the HSI would use a fraction for further investments, branching out, diversifying their capital stock and creating additional research and services. At the payee’s end of life, the collected funds would be transferred to the declared recipient; either child or grandchild, with added interest.

This would result in a care service which would be free for members; due to continued commitment to their subscription payments, and a limited fee for non-members.

Healthcare in the UK is in desperate need of reform. We continue to not help our national situation by being in a state of denial and nostalgia for days and standards to which never even existed. One type of private healthcare would be as effective as a nationalised system; it cannot meet the demands of all. If universality is the principle which British people refuse to budge on, then a private system with a diverse way of providing care has a greater chance; allowing a wide variety of methods for providing care, would ensure a greater degree of people have access to care; we have a variety of methods for providing other products, so why not healthcare? Rather than an ultimatum between ‘for-profit or nothing’, or ‘nationalised or nothing’, let’s try a decentralised, denationalised variety of choice.

For-Profit, Non-Profit, Charities, One-to-One Personal Family Doctors, Healthcare-Subscription-Institutions; whichever you subjectively prefer, choice is the best cure for healthcare.

Sources:

- Kristian Niemietz: Universal Healthcare Without the NHS (pp. 19-21)

- Nick Hayes: English Historical Review (p. 659)

- Kristian Niemietz: Universal Healthcare Without the NHS (pp. 24-25)

- http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/health-news/nhs-uk-now-has-one-of-the-worst-healthcare-systems-in-the-developed-world-according-to-oecd-report-a6721401.html

- http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/8d3cc7e8-8267-11e5-a01c-8650859a4767.html

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/317669/healthcare-expenditure-in-the-united-kingdom/

- Kristian Niemietz: Universal Healthcare Without the NHS (pp. 36-41)

- Kristian Niemietz: Universal Healthcare Without the NHS (pp. 28-29)

- Kristian Niemietz: Universal Healthcare Without the NHS (pp. 32-33)

- Kristian Niemietz: Universal Healthcare Without the NHS (pp. 93-94)

- Kristian Niemietz: Universal Healthcare Without the NHS (pp. 107-108)

- Kristian Niemietz: Universal Healthcare Without the NHS (pp. 112-113)

- Jacob Hornberger: The Dangers of Socialised Medicine (p. 15)

- Jacob Hornberger: The Dangers of Socialised Medicine (p. 65)

- Jacob Hornberger: The Dangers of Socialised Medicine (p. 61)

- Jacob Hornberger: The Dangers of Socialised Medicine (p. 18)

- Jacob Hornberger: The Dangers of Socialised Medicine (p. 22)

- Jacob Hornberger: The Dangers of Socialised Medicine (pp. 40-41)

- Free-Market Medical Care | Timothy D. Terrell (2018) YouTube video, added by misesmedia [online]

- https://www.littler.com/stork-has-landed-california-employers-must-maintain-and-insurers-must-provide-pregnancy-benefits

- https://www.ehealthinsurance.com/resources/individual-and-family/does-your-state-require-you-to-have-health-insurance

- Miller, Benjamin, and North: The Economics of Public Issues (pp. 4-5)

- Issues in the Economics of Medical Care | Timothy D. Terrell (2014) YouTube video, added by misesmedia [online]

- Jacob Hornberger: The Dangers of Socialised Medicine (p. 14)

https://pixabay.com/photos/ecg-electrocardiogram-stethoscope-1953179/