Economic Piece by Josh L. Ascough

– This article is part of a larger collection of my work I hope to have available soon, titled; ‘The Social Science Of The Market’. –

It would be very easy to simply “fallacy shame” those who are inclined to believe fallacies with regard to economic science; to turn to the layman and say “you are a science denier!” without explaining why these falsehoods are not just wrong, but dangerous, as they are counter to the science of Economics.

However, an economist, and those well minded in the science without the official title, should do well to explain where these fallacies are, why they are dangerous, and what the reality is.

Throughout this article, I shall attempt to explain two important subjects that hold dangerous consequences; these are price gouging, and price controls.

Price Gouging: – Price Gouging is a non-scientific term used to define when the price of a certain, or many economic goods, sees an increase in the cost to consumers. This fallacy is often used in times of crises, such as a natural disaster, and is predominantly used to attack apparent “greedy business owners” for “taking advantage”. But the reality is the price has seen an increase because market conditions have changed; people’s use for the economic good in question has seen an increase in the quantity demanded, which is above the supply levels, and through consumer actions has seen its value increase. This is no different to when the supply of a good sees an increase, the consumer demand of specific quantity levels has stayed inelastic, and so the equilibrium of value reflected in the price decreases.

“Thanks to the pricing system being allowed to reflect value through supply and demand, Amazon was able to adjust to better bring supply to meet the consumer demand”

Price increases of this degree do not simply occur because a business became greedy overnight; an economising business does not simply look at current levels of supply and the quantities demanded, but will look at predicted future levels and value; if a disaster has occurred, causing people’s demand for a certain economic good to increase and it is predicted that consumers quantity levels demanded are likely to increase over time or stay at the current high levels, then the business will increase the cost to a higher level because (A) the value of the good has seen an increase and (B) this ensures the business can refrain from having its supply depleted causing it to be unable to meet future demand quantities, and through its predicted models will be in a position to better afford materials to meet the supply levels demanded. An example of this occurring can be seen with Amazon during the early outbreak of COVID-19: During the early period there was a spike in demand for hand sanitizer gel. This caused the dreaded “price gouging” to occur with most notably Amazon at the time selling 50ml bottles for upwards of £12; the consumer use for the economic good had seen an increase, shown through large numbers of consumers buying larger quantities than previously, causing the value to increase and the pricing system to take effect. After this period of the equilibrium of value meeting consumers quantities demanded and producer quantities suppliable, Amazon later found itself in a position to sell hand sanitizer gels of 50ml for an average price of £4.50 (subject to brand). Thanks to the pricing system being allowed to reflect value through supply and demand, Amazon was able to adjust to better bring supply to meet the consumer demand.

The scientific term used for both increases and decreases in a price, is Price Fluctuation; it is not producers who cause prices to increase or decrease, it is consumers through their choices, values and actions. Price Fluctuations (I will use the scientific term hence forth), not only play an important role in a market economy, as they help to coordinate courses, allocate resources and incentivise choices through identifying what uses and needs people are prioritising and placing higher value on, but they play a significantly high role in times of crises, as higher fluctuations in prices help to disincentivise panic buyers and hoarders taking supply quantities which go beyond their use value to them.

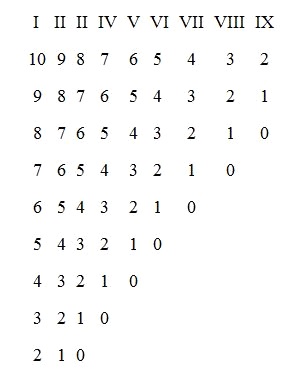

For an example, let us say during the early stages of a crisis, person A has £250 to spend on resources to satisfy his needs; he requires food for himself, his wife and baby, paracetamol, hand sanitizer, toilet roll and diesel. Let us also say that the pricing system has been allowed to take effect, and has not been tampered with to pass inaccurate signals through price controls; baby formula has seen an increase from £8.99 for 900g to £20, canned food has seen an increase from £0.79 per can to £3 per can, frozen microwave meals have seen an increase from £2.50 to £5, fresh meat has seen an increase from £3.50 to £10, paracetamol £0.50 to £3, hand sanitizer £0.99 to £12, toilet roll £3 per x4 pack to £8 per x4 pack, and diesel with an increase from £5.90 per litre to £10.60 per litre. If he is an economizing individual, he will utilize his resources the way which best allows him to satisfy the needs he deems to be a priority in relation to the use period of time they are required to serve. We can better imagine this organization through a 1 to 10 chart; 1 being the least valuable or that which serves a lesser need, and 10 being the most valuable or that which serves higher needs.

If person A is an economizing man, he will look at the price alongside his means to enact an exchange, and look to satisfy his and his family’s needs through goods which serve to satisfy said needs based on their use value, and time scale of necessity to him. Let us say he has a high use value for food for himself and his family, and wishes it to serve a long time period; the economizing man will look to primarily satisfy these needs over what he considers his second and third most important needs, say paracetamol at second and toilet roll at third. This places food at the position of 10 on the scale, paracetamol at 9 and toilet paper at 8. While he sees a need for hand sanitizer it does not serve a regular use such as food and he only finds use for it when in contact with unclean items or items he has no control over; he recognises his use will be satisfied with one drop, and so he looks to maximise its time period of use through only taking command of the good when needed; this will place the hand sanitizer at a position of 4 on the scale. Placing the sanitizer in a position of 4 allows him to have command of more of his resources, that of money, should he find an unexpected need for further food or one of the other goods of higher value than 4, but below 10. If person A continues to act in an economizing manner, and has little use for travel during the crisis, then he will look to only utilize his means of transport in order to better satisfy his needs, or future needs which may arise; placing diesel at a position of 3 on the scale.

This would mean person A would roughly spend £100 on food, £12 on paracetamol, £16 on toilet roll, £12 on sanitizer, and £42.40 on diesel, leaving the economizing individual with £67.60 for a reserve should needs of higher value require further satisfaction or a good of lower value in order to serve his needs of higher value at a higher quantity at a later period.

“This in turn disincentivises person A from hoarding and leaves resources available for other economizing individuals looking to serve their needs and, in the long term, allows businesses to adjust their supply levels”

A further, shorter example of this would be the following: if person A needs £3 worth of toilet roll per x4 pack but he wishes to purchase £16 worth which exceeds their use value to him; should the price increase to £16, he will economise by making a purchase which allows them to serve their use value in relation to the exchange value of his good without excess to ensure he can better serve and maximise the satisfaction of needs he deems to be of higher value. This in turn disincentivises person A from hoarding and leaves resources available for other economizing individuals looking to serve their needs and, in the long term, allows businesses to adjust their supply levels with the additional income so as to better meet quantities demanded in the future.

Price Controls – Continuing down the road from “Price Gouging”, as briefly mentioned in the fallacy above, one method which is often attempted during high price fluctuations is price control. This is when a high price fluctuation for an economic good is deemed “immoral” and so policy makers look to enact price controls to halt prices from rising, and decrease them to “acceptable” levels. This however, as will be explained, is a dangerous measure to take.

Price controls have been a tried and tested measure of failure, most notably within the housing market. When a price fluctuation occurs, it is not through reckless desire by the business in question, it is a reflection of consumer demands, quantities demanded, and a higher degree of value being placed on the economic good; these act as signals to producers, investors, and entrepreneurs that a high equilibrium of subjective value is being placed on an economic good; either of higher or lower order (lower order being direct consumption, higher order being economic goods such as material, labour, land, or capital; goods not designed for consumption, but for further production). Goods of both higher and lower order fall under the pricing system, which sends signals to which goods of economic qualities are in demand; if a large shift is seen in the number of those engaging in the consumption of vegan food for example, this sends signals to the sellers of the final good that consumers value the vegan products they are selling over the non-vegan products. This in turn sends signals to the industries which produce the ingredients (goods of higher order) that sellers are expected to increase their demand for stock, which engages these industries to be more competitive for resources as they have increased in value, as each party is sending signals that they place a higher value on the economic goods; from consumer to investor.

In addition, these signals of high demand assist the entrepreneur in calculating the risks of bringing new, innovative goods to the market and allows him to assess his opportunity costs*; without these signals of supply and demand representing an equilibrium of value, the entrepreneur risks his resources on outputs which hold little to no value.*

*An Opportunity Cost is the assessment of resources available to the economizing individual and what could be, or could’ve been created, consumed, invested in, or sold. As an example if I hold command over leather, I could sell this to a sofa maker, a jacket maker, or sell it on an open market directly to consumers as a material they hold use value for; if I hold command over 1000 pieces of leather, and I choose to sell 600 to sofa makers, I cannot sell 600 to jacket makers and can only sell 400 thereafter. The opportunity costs are the economic option I chose not to engage in, and is an important aspect of determining where resources go and where they are best allocated.

*This does not mean if an entrepreneur sees a high demand for a specific vegan food (such as vegan bacon) he will only look to create more vegan bacon, but that he will see an increase in value for vegan products, and look to innovate the vegan market; this could be in the form of creating new ways to produce vegan products, finding economic goods which have yet to have vegan alternatives, or find ways of enhancing the vegan goods through extracting animal DNA to grow meat products without the killing of an animal.

With all that said, let us get back to the topic of price controls.

When legislators put into action price controls, this causes the signals used to display supply and demand to be artificially altered, and send false signals to buyers and sellers that the value of the economic good in question has not changed. Price controls cease the pricing system to signal to consumers as to the change in economic value, and so the consumer is not faced with changing their consumption patterns.

This act also disincentivises investors, entrepreneurs, sellers and producers from bringing more of the economic good to the market, as the pricing system has not been allowed to reflect any equilibrium of value, and so those in these categories will not be able to meet new levels of quantities demanded, causing long term shortages; this in turn, hurts the consumer base of the economic good in the long run too, not just the suppliers, as it is not seen as a wise investment to place resources into a good which has not been permitted to reflect its overall value.

Price controls do not just occur in the form of artificially lowering the price to a “justified” level, they can also occur in the form of minimum pricing; this type of policy tends to arise if a company is suspected of “dumping” goods on to consumers, in an attempt to dismantle competition and become a monopoly; this type of price control can often be found in most Anti-Trust laws.

The minimum price form of price controls is dangerous for very similar reasons to the price controls mentioned above; in this instance though, the disincentive is with the consumer rather than the supplier.

As before, the artificial increase in a price, misinforms those engaged in the market as to the value of the economic good in question, and sends false signals to suppliers as to what consumers are in high demand of. The value of an economic good is based within the subjective values and needs the good as a subject serves; it is subject to the use value of the individual wishing to consume the economic good being higher than the individuals exchange value of the good he is to trade for the good, and the exchange value of the good to be higher to the supplier than its use value; this in turn creates an equilibrium of value, which is displayed in the pricing system and determines an economic goods overall market value.

If this system of value is not permitted to function (in this instance subject to the form of minimum pricing), then the actual value of an economic good is not being allocated; if this is above the use value the consumer places on the good, it will create disincentive for the consumption of said good; causing losses to be made on the sides of both parties, as if the consumer is forced to pay a price above the equilibrium level of value, he has less access to resources at his disposal for the consumption of economic goods he is in need of service from which can satisfy his additional needs, if the supplier is forced to charge a price above what he initially was willing to sell the good for and above what the consumer values, he will be wasting resources, and losing profits which would’ve gone to the further production of goods in demand.

Prices need to be allowed to work, not through the artificial lowering or heightening of the value, or both parties wishing to engage in mutual benefit will be faced with non-consensual losses; disincentivising further engagement. Price controls ultimately hurt the poorest by being forced out of market engagement, and hinders new, small businesses from entering engagement of the market, damages the competitive process and, in the end, slows innovation.

Monopoly And Competition – I have chosen to combine both the fallacies of monopolies and competition together, as there is a prominent, black and white view of the two as to how they correlate; there is nuance with both and not all monopolies are damaging and not all competition is beneficial.

We must first go over the subject of a monopoly. There are three forms of monopoly, which are:

- Legal Monopoly.

- Market Monopoly.

- Community Monopoly.

“the UK’s NHS holding a legal, centralised monopoly over the health industry to forcefully extract resources from citizens, irrespective of whether they value the particular good”

The legal monopoly is best described, as an institution, company or industry, which has been granted a special, legal status to protect it from competition. This can appear in the form of a copyright over a product (not a brand), power to restrict competition via methods of selective entry and through licencing laws (a case example is the American Medical Association, which up until the 1970s, lobbied to Congress to grant it special licencing powers and to restrict how many graduates could enter the market at any given time, in order to keep wages high), but is most notably found within government institutions, as these institutions do not operate under a market system through pricing based on supply and demand, but demand payment from “potential” consumers through means of assumed consent, regardless of quantities demanded (or lack thereof) from consumers; many government institutions also operate as “safeguards” of deciding who can enter the area of a market the government institution has a legal monopoly over; examples of this can be seen with the UK’s TFL (Transport For London) holding the monopoly power to issue or take away licences from private competitors, as well as with the UK’s NHS holding a legal, centralised monopoly over the health industry to forcefully extract resources from citizens, irrespective of whether they value the particular good.

This form of monopoly, the reader would be right in assuming, is damaging to not just competition, but the quality and quantity of economic goods available to the consumer. Through the means of a legal monopoly, competition becomes either too expensive to warrant investment, or illegal. Competition and the pricing system go hand in hand, and are vital to determining how to allocate resources to where they will best serve the maximum demand which serves a need individuals wish to see satisfied.

This note of competition brings us to our second form of monopoly, the market monopoly.

The market monopoly is exactly as is named; it is a monopoly which has arisen through market activity.

This form of monopoly has a tendency to attract the most suspicion; however, a market monopoly is merely created through consumers placing a higher value on the particular goods to which the company in question is selling.

Market monopolies are not created through legal means such as selective entry*, licencing laws or forcefully extracting income from consumers regardless of demand, but are created through consumer choices. If the majority of consumers choose to purchase iPhones’ over Androids’ because their use value for the economic good is higher than the exchange value of their money, the quality meets or exceeds their subjective standards or a combination of both, Apple will naturally acquire a market monopoly, because it is more efficient at serving its consumer base and the consumers use value of the item, than its competitors.

The market monopoly has often been accused of stifling competition in an attempt to restrict consumer choice, there is a major flaw with this hypothesis though; the monopoly can only occur through consumer choices within a competitive market; you cannot save all or any competitors if they are not able to perform as well at providing a service consumers value than their competition that can.

Market monopolies do not occur due to a lack of competition, they occur because the competition lacked efficiency at providing the particular economic good consumers demanded, and this lack of efficiency is reflected through the actions and choices of consumers.

“Market monopolies do not hinder consumer choice, as has been stated; it is through consumer choice this form of monopoly occurs; through consumer choice, market monopolies actually encourage innovation in being able to compete for the top position of serving consumer demand the most”

Market monopolies do not hinder consumer choice, as has been stated; it is through consumer choice this form of monopoly occurs; through consumer choice, market monopolies actually encourage innovation in being able to compete for the top position of serving consumer demand the most. Is this monopoly expected to last a long time? Yes. Is it expected to last forever? Unless the company in question is exceptionally good at predictions of future quantities and qualities demanded by consumers and adapts accordingly to change, and prices its goods to reflect demand and use value; continually meeting an equilibrium of value, no; peoples’ evaluation, values, tastes, needs and priorities change and adapt over time, an example of this change would the vegan food industry vs the meat industry; not that long ago farmers appeared to have an unending dominance over the food industry, but as peoples’ value over animal life changes and demand for alternatives arise, the meat industry’s market monopoly becomes crippled, and has to adapt to the change in value, though it is a shame the meat industry, particularly in the UK has resorted to demanding subsidies and bailouts, because it cannot grasp the change in consumer demand or competition, which isn’t a legal monopoly per say, yet it does fall into a much wider issue which we will go over later in this chapter.

All industries, under a market economy, can and will bend to creative destruction, through entrepreneurship and the private ownership of the means of production.

An example of a market monopoly would be Microsoft.

When Microsoft first began selling household computers, it provided its own internet browser for free. Before this, consumers would have to buy a browser for their home computers. This genius act of innovation for consumers gave Microsoft a market monopoly over household computers, with many of its competitors decreeing Microsoft to be “dumping” on consumers and called out for Anti-Trust to be enacted upon the company.

This brings us to our third form of monopoly, the community monopoly.

The community monopoly, could be considered a pointless subject to delve into, as it tends to be the most short lived, and very few take issue with this; however for the sake of consistency and to wrap up, I will go into this monopoly briefly.

A community monopoly occurs when there is a particular area of the market, which has yet to reach a community, regardless of size of the community or the industry itself.

If a community has no provider of pizza delivery services, yet there is ample demand for pizza delivery and I decide to open up shop, due to being the only provider for this community I have achieved a community monopoly.

This form of monopoly in previous years would never last long if there was demand for the service and demand continued or grew, as since my prices would reflect the equilibrium of value relating supply and demand, the use value and exchange value of both parties involved, other business owners would see there to be demand and money to be made in this industry within said community, and these competitors would cause me to exit the market if they were able to provide the service with more efficiency, and the consumer not only found greater value with the goods of my competitors, but could better satisfy their needs to greater quantities with an exchange more attractive to them and provided use value higher than the exchange value of their money.

The community monopoly is a rarity in the modern world, as we have become a much more global market, with a wider range of methods for individuals to acquire goods in order to satisfy their needs; this should not be seen as a good thing or a bad thing, but should be a grand example of how the organic market has created new, innovative ways of serving, satisfying, and providing to individual subjective needs and value; commerce is truly, a beautiful and exciting experience to watch expand.

I will leave the reader with a quote by the late Economist, Milton Friedman, to which I hope the reader considers when presented with future, “quick fix” and “moral” solutions:

“One of the great mistakes is to judge policies and programs by their intentions rather than their results.”

Josh L. Ascough is on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/j.l.ascough/

Image from https://pixabay.com/photos/board-chalk-finance-graphic-chart-3704096/

One thought on “Price Gouging, Price Controls & Monopolies – An Analysis of Economic Fallacies”

Comments are closed.