Image: https://pixabay.com/photos/lake-sunset-duck-pear-light-bulb-2592276/

Economic Piece by Josh L. Ascough

The market economy and the environment are often seen as at complete odds with one another; with pollution, deforestation, animal extinction, and a whole host of other issues, the easy option is to blame profit seekers and other apparent villains in the world.

The go-to argument for environmentalists; or rather, watermelon environmentalists (green on the outside, red on the inside), is to tax, regulate, ban, and in some instances nationalise, because the market has failed us. On the contrary however, the market hasn’t failed us, because one of the key aspects of a market system has been failed by governments refusal to protect it; namely the institution of private property rights.

I wish to present to the reader the concept of Free Market Environmentalism. This concept decrees that protection of the environment is a losing battle without the acknowledgement, the expansion and the upholding of private property.

Throughout this article we will go over a few key areas; these include:

- The One-Dimensional Scarcity View of Environmentalists.

- Time Fallacy of Market Short-Sightedness.

- Consumer Choice.

- Negative Feedback Mechanism.

- Relative Prices vs Absolute Prices.

- Substitutions/Back-Stops.

- The Kuznets Curve.

After these key areas have been covered, we will go into a few primary areas of environmental concern; these are:

- Pollution.

- Deforestation

- Recycling.

- Animal Extinction.

One-Dimensional Scarcity

The Environmentalists seem to have a One-Dimensional view of scarcity, with regards to non-renewable resources. The argument being that the more and more non-renewable resources we use, the more we leave drastically fewer; if not zero, for future generations. This has tended to be one of the arguments for recycling. However, there are serious issues with this theory.

The use of natural resources or non-renewable resources in the current time frame does not mean we risk reducing the options for future generations in future time frames; instead, it provides future generations with a whole host of different options. This does not mean that there is no argument for recycling however, there is an argument in favour of recycling for the purposes of reallocating how we dispose of non-biodegradable resources, so as to pollute as little as possible; what is not an argument for recycling is the One-Dimensional Scarcity view, which runs contrast to Back-Stops and the fact of capital goods being Multi-Specific.

Back-Stops refer to a close substitute resource which can be utilised for a particular price. The ability and options for the substitute or “back-stop” to be swapped in, places a limit on the price increase of said given resource. If the back-stop is competitive and has multi opportunities for use, the original scarce resource it is a substitute to will eventually leave the market. However, if the back-stop is competitive in only a limited number of uses; or in solely one, then the price of the original scarce resource will continue to rise. (This ties into the Multi-Specific quality of capital goods.) The use of the original scarce resource will be allocated to those purposes that the substitute is a less effective replacement. Some may argue that this only encourages us to squander resources until we can no longer meet traditional demands; an alternative argument however, would be that this adjustment has allowed us to incorporate a cheaper substitute, that is just as effective; if not more, for meeting demands.

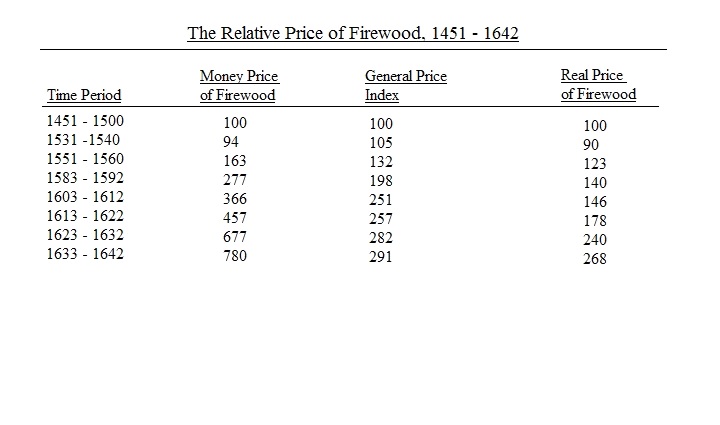

A historical example would be the substitution of coal for firewood in England during the period of 1450 to the 1700s. Around 1500 a shortage of firewood had occurred. John U. Nef in his book, The Rise of the British Coal Industry, noted that:

“All the evidence suggests that between the accession of Elizabeth and the Civil War, England, Wales, and Scotland faced an acute shortage of wood, which was common to most parts of the island” – page 158-161.

As expected, the substitution of coal proceeded at different rates for different industries due to time patterns; Nef further notes that:

“There were a large number of industrial situations in which coal could not be substituted at all until some technical alteration had been made in the process of manufacture. It was necessary either to free the coal from its damaging properties or to invent a device to protect the raw material from the flames and fumes” – page 215.

Relative Prices vs Absolute Prices

This type of change in market activity cannot be expected to occur however in a situation of absolute changes in prices. Confusion or misunderstanding in the real price can occur if absolute prices; due to an overall inflation, are not seen as separate to relative prices.

As stated above, an overall price increase occurs due to inflation, we can predict the effects on energy use or the use of another good or service based on relative price changes against other market prices. Only when the prices are relative, will they have an effect on how consumers utilise these resources, how much they take in, and how much are saved for future consumption based within an allocated time preference. However, when the price of energy, wood, water; or any other consumption good or capital good, sees an increase that is due to a general increase in prices, the incentive to economise on resources is no different than if prices had not been effected and a reflection of inflation. Thus, the argument mentioned above with regards to substitution, must be based in changes to the price of the particular good or service, relative to other prices.

This talk of relative and absolute prices brings us on to the subject of the Negative Feedback Mechanism.

Negative Feedback Mechanism

One of the ways Economics shares similarities with Ecology, is with regards to the negative feedback mechanism found in nature; which works on a similar basis in economics.

In nature, a negative feedback mechanism occurs within an eco-system when a stimulus provokes an offsetting response; a similar mechanism exists in the market, and ensures that the market can operate as a conserving system. For example, let us suppose new information is discovered which indicates previously perceived stock ‘x’ resource is incorrect and overestimated. Resource owners will react to this by adjusting their prices upward to meet expected demand in relation to the new understanding of the supply levels. This adjustment to an expected higher future price will create a time preference for future consumption as opposed to current consumption. The reduced supply of ‘x’ resource will hold consequences for the present. Prices for current consumption will be forced to rise in order to meet equilibrium. In addition on the demand side, users of ‘x’ resource and its by-products will be incentivised to limit their consumption of the resource or to find substitutes which can satisfy their marginal utility. The incentive to develop techniques that economise on the use of ‘x’ resource will be increased. Similar will occur with regards to the supply side. The search for new deposits will intensify and lower-grade sources will become profitable to use. This is a core aspect of the pricing system. It acts as a measuring line of value and a feedback mechanism for achieving many of the responses desired by the environmentalists. Consumers are faced with incentives to limit their consumption, and producers are faced with incentives to limit their use or; due to the multi-specific nature of capital goods, find substitutes or back-stops to meet production requirements of inputs; so long as the marginal costs do not outweigh the returns.

This pricing system we talk about; if allowed to operate and not face intervention from busy bodies and self-declared angels which skew market signals and give us false information, ensures that the market system can work perfectly, as it is able to calculate the marginal values of the consumers, against the marginal costs of the producers; or in other words, the costs/risks verses the profits/benefits; so long as the price paid by users reflects all benefits derived, including aesthetic and other benefits.

This price system and the negative feedback mechanism, ensures that decision makers are faced with prices for resources at all times in the future. Any resource owner is able to sell his resources at the times that are to his greatest benefit. Resource owners must decide how much to use today and how much to save for the future. If the resource owner is economically rational, he will look to gain the most he can for his resources by comparing current prices with prices he expects in the future and plans his use of the resource accordingly. The higher the price he expects in the future, the more the owner will conserve his resource so as to increase profits.

Time Fallacy of Market Short-Sightedness

There is an assumption among environmentalists that the market system, business owners and other property owners are short-sighted and only look to short term gains, this however could not be further from the truth.

The private ownership of property and the means of production incentivises people to maximise the value of their property, and in so doing, look to analyse the cost and benefits of their market activity. The private ownership allows the owner(s) to understand their opportunity costs for and against current consumption, plus for and against future consumption.

It should be stated however, that even in the event of selling a resource at a current time frame for current use, this does not mean this is the only available alternative as opposed to the resource being saved for the future. If the original resource owner sells his property to a willing buyer, and said buyer expects prices to be higher; at least enough to cover the costs, the buyer who plans to buy the resource will be willing to not only pay more than the present users, but will have an incentive to conserve his new property, in relation to the time preference of interest. Therefore, even though the time frame for one particular owner may be short-sighted, the preservation of the resource will be achieved by the transfer to different investors, and to those entrepreneurs who see an untapped area of the market, to which there is disequilibrium.

Time frames over resources are not simply seen directly, they are also shown in the indirect holding of resources; particularly non-renewable resources. Institutions such as the stock market, stock exchange and mutual funds, ensure and allow for the continual buying and selling of resources, and claims to ownership. These play an important role in how we incorporate the future preferences into current decision making.

While the market system allows for the values of future generations and future time frames to hold an influence, the link between future scarcity and the preservation of resources can be broken; and often is broken. For example, the mechanism cannot be expected to function when ownership rights to a resource are limited. The temporary owner of the resource will not gain from any future value that the resource may hold, nor from the higher prices of consumer future time preferences for consumption. Due to this limited tenure, there is less emphasis on preservation of the resources and a stronger incentive to sell the resource at a current time frame. As an example of this, if there was a regulation in place over a natural resource; such as a forest, to which if an owner had a fixed time period they were permitted to sell this resource, after which it would go into public ownership, the incentive to preserve the resource for future consumption based on expected higher prices, would be in the negative.

This link can also be broken under permanent ownership, if current resource owners believe the rules are about to change, such as the nationalisation of resources presently owned by private bodies. The threat of nationalisation creates the same short-term incentives for current time frames as that of the limited mentioned above. The soon to be former owner faces no advantage from the higher prices or marginal values of future time frames that occur after the nationalisation, and so faces no opportunity cost in selling his resources all at once; it very much makes the term “use it or lose it” a reality, and a dangerous one at that.

Consumer Choice

Within the market system, we must understand that the individual consumer is sovereign. This consumer sovereignty refers to the uncoerced freedom for consumers to choose goods and services from a wide host of sellers and producers; competing with each other who in addition provide information about their output, to best serve the satisfaction of their customers. The sovereignty of the consumer is limited however, as a producer will not allow himself to sell goods and services at a price that does not cover the costs; just as a consumer will not pay a price higher than his marginal value of the good or service. What is to be produced is determined by the money votes of consumers; not every 2-4 years at the polls but every day in their decisions to purchase this item or not that item.

Note: consumer votes themselves do not on their own determine what goods are produced. Demand has to meet supply of goods; so business cost and supply decisions alongside consumer demand, assist each other in determining what is produced.

“as we get richer, we place a higher value on this good and are more willing and able to keep it clean. So humans; as their incomes increase, have a better environment overall”

The Kuznets Curve

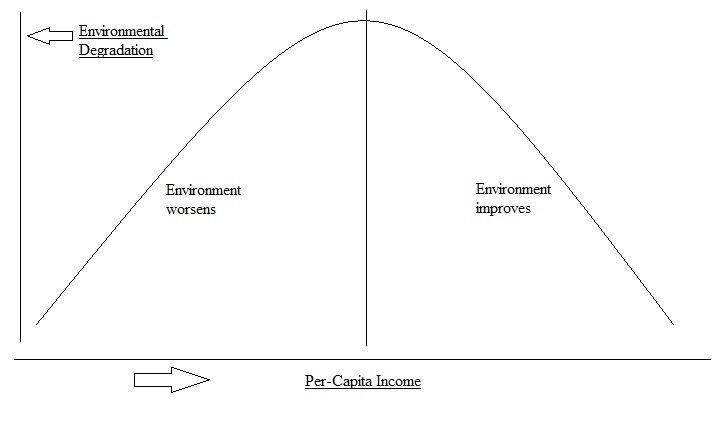

The Kuznets Curve is a relationship between environmental quality and economic output; measured by per-capita income.

What the curve shows is that when economic activity first starts to develop and wealth begins to develop, the environmental quality; for a period, becomes worse off, because now activities are being enacted which impact the environment, but there is not enough wealth or monetary productivity to incentivise the maintenance and clean-up of the environment.

As a country becomes richer; or on a micro level as a household becomes richer, the costs of maintenance in proportion to income becomes so that, maintenance becomes a desired activity as the environment becomes what is known as a normal good in economics; as we get richer, we place a higher value on this good and are more willing and able to keep it clean. So humans; as their incomes increase, have a better environment overall.

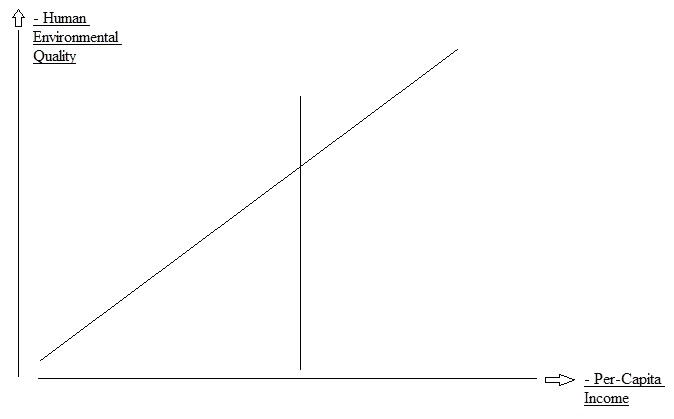

However, if we were to measure the environment purely from how humans experience it, then rather than being a curve, it would be a line continuously going up:

“all human activities have trade-offs, and one of the core differences between humans and other animals; being that other animals must adapt themselves to their environment, whereas humans must adapt their environment to them”

The reason for mentioning the second is that, prior to industrialisation, the environment for humans was of low quality. As an example anyone who has ever gone camping knows that they will get the smoke all over them; that’s air quality. What the Kuznets Curve is making look like a worse environment; when looking at it from an external perspective at the beginning, is really a better human environment than the previous point as it continues.

This in no way discredits the Kuznets Curve; merely it gives a more internal human perspective as to how humans experience the environment around them, rather than solely the external environmental perspective. If we take into consideration that all human activities have trade-offs, and one of the core differences between humans and other animals; being that other animals must adapt themselves to their environment, whereas humans must adapt their environment to them, we realise that both the curve and the line need to be taken into consideration, when considering the trade-offs of economic and environmental activity.

Now that these key areas have been looked into, let us delve into a few core environmental issues that tend to be high up on the list of concerns. While all of these will have some degrees of difference when it comes to the problems and the solutions, they all share two traits for solutions in common:

Privatisation and Property Rights.

We will delve into how each will be benefitted by these institutions as we go into them.

Pollution.

You cannot possibly talk about environmental issues without getting into the topic of pollution; you could say it pollutes the discussion…get it? Anyway my dry humour aside.

Pollution occurs as a by-product of producing goods and services that satisfy consumer wants-needs. When we talk about pollution we are primarily taking into consideration spraying fumes into the air, dumping garbage into the ocean, and throwing items such as empty plastic bottles on to the ground. Many nations have tried to solve these problems by issuing fines, enacting regulations, banning certain products and a whole host of other solutions; the problem is these solutions aim their sights on the approximate cause rather than the ultimate cause.

The activities themselves are the approximate cause; or they could be seen as negative incentives; the ultimate causation comes down to the following:

- The Tragedy of the Commons.

- “The Public Good”.

- Lack of Private Property Rights.

The Tragedy of the Commons refers to when everybody or nobody has a claim of ownership to a resource, which leads to a lack of opportunity cost; for example if I have no claim to ownership over a piece of land where lots of herbs grow, since I nor anybody else has a claim of ownership there is no opportunity cost for extracting all of the herbs for myself, because if I didn’t I wouldn’t have them anyway, and so resources under The Tragedy of the Commons are at risk of becoming depleted or damaged.

Many governments have tried to solve this problem by telling private firms they’re only allowed to take a certain percentage of the resource; such as cutting down a certain number of trees. The issue here is that the problem of the commons still persists; because the private firm has no incentive based on an opportunity costs (due to there not being one), it will simply take the maximum of what it is permitted to take.

To put this into a bit more of a perspective, suppose you have a garden as part of your private home, because of the private ownership there is a high incentive to keep the garden clean in order to maintain the value of the home; however if the garden, and the entirety of the home were to have no claim of private ownership, there would be no manner to measure the cost and benefits of maintenance due to there being no opportunity cost. This would lead to (A) the occupant facing no incentive to keep the home clean, and (B) his community as a whole misusing the resource and using it as a dumping ground. If we then magnify that, it reflects the problem we have with the pollution of oceans, air and land.

Another area mentioned above is the concept of “the public good”. The problem with the public good concept, is that if a particular industry is seen (by government) to offer a large enough social/public benefit, any pollution it brings about is fair game; regardless of any private property rights being infringed. A modern day example of this concept manifested into political policy would be HS2 and the policy of Eminent Domain.

Eminent Domain provides the government with the power to seize the private property of citizens, or demolish landscapes in order for the enactment of projects seen to be within the public interest. These political powers can also been given to private companies if their endeavours are seen to have a high net public benefit. Under the law of Eminent Domain, if the firm or government department running the operations requires land that private property is situated on, the property owner is legally required to participate in compulsory purchase; where in most cases they are given a set amount of “compensation”; usually below the value of the property, and are required to accept the set amount; if the property owner should attempt to refuse, they will either have their property demolished without payment, or they will be taken to court.

In addition, another issue with the concept of “public good” is that it creates negative incentives, as if you are an environmentally friendly business owner and you want to produce goods that are ecologically safer, under the guise of public good you’ll be at a competitive disadvantage; your competitors don’t face any injunctions for damaging private property if their endeavours are seen to be in the public interest, so overall it costs you more to be environmentally friendly than it does for your competitors to damage property and infringe on property rights.

Both of these areas culminate under the issue of a lack of private property rights, and a lack of property rights being upheld.

So we have a basic premise of the problem, so what is the solution?

While there are certain degrees of difference with the solutions, they all would fall under the promotion of privatisation and private property rights.

We can give a historical example of how private property rights would work for the environment.

In the 1830s and 1840s, there were a number of lawsuits in the United Kingdom, the US and Canada against pollution from coal factories, by property owners who had received damages. Typically a woman would go to court under the common law of nuisance and complain that a coal factory was spewing smoke soot and dust particles over her property, resulting in her laundry being dirty and damaged. Or in other instances a farmer would complain about a rail train that would pass by and sparks would fly from the tracks, resulting in his haystacks catching on fire. The individual in question in other words would allege that their property rights were being violated, and would appeal to the courts for payment to cover damages and for an injunction to stop the polluter. In most cases, especially in cases where the property owner had homesteaded, the courts would rule in favour of the accuser.

If taking into consideration the historical example, the issue of pollution could be solved, if we were to privatise land and uphold the protection of private property rights.

The way in which to do this would be to first conclude who holds a claim to what. This feat would be achieved by using the Lockean theory of Homesteading. The theory of homesteading states that he who uses the land first for his labour is the one with a legitimate claim of ownership. Heathrow airport as an example has consistently come under criticism for expansion after expansion, and for continuously looking to expand further. However, many communities have existed in the area long before expansions were sought after, and so under the Lockean theory of Homesteading, if eminent domain laws were abolished, the rightful owners of the land would be the home owners and Heathrow airport would have to either set up a contract with the community detailing what they’re permitted to do in terms of air/noise pollution levels, buy out the land from the home owners, or they would have to find alternative ways to expand without expanding on noise pollution or air pollution, keeping within the vicinity of the area they themselves have homesteaded; i.e. encouraging innovation. If they failed to do this and they were found to have damaged private property, the property owners would be able to bring Heathrow to court for an injunction and to cover damages.

Many may say that such privatisation wouldn’t work when it comes to roads; that you couldn’t bring every car owner to court if they polluted over a certain amount that would damage others property.

It is true that it would be unfeasible to sue each and every car owner, however if we had private roads, then in the case where a car owner’s car was spewing dust and soot to the point that it brought damages to another’s private property, then the owner of the road would face an injunction to cut down on the pollution and be faced with paying for damages. The private road owner would also face incentives to reduce the pollution on his road, due to wanting to maximise the value of his property, in order to gain long term value; as stated previously, if a private owner faces not being able to reap the benefits and the full value of his property, he will not look to maintaining it due to the fact he is unable to benefit from it; if we had private ownership of roads, then the owner would look to maintain the value of his property for the long term and therefore would add into the costs of using his road the costs of maintaining the road. This would ultimately be reflected in the prices drivers face; for example it could be seen that the price for using the road would be 50p per mile for hybrids, £1 per mile for cars, £3 per mile for lorries, and £5 per mile for vehicles over a certain age that were more at risk of producing higher levels of toxicity.

In addition this would ensure that, costs known as negative externalities would have a way of being measured into the marginal costs, so as to better communicate into the pricing system.

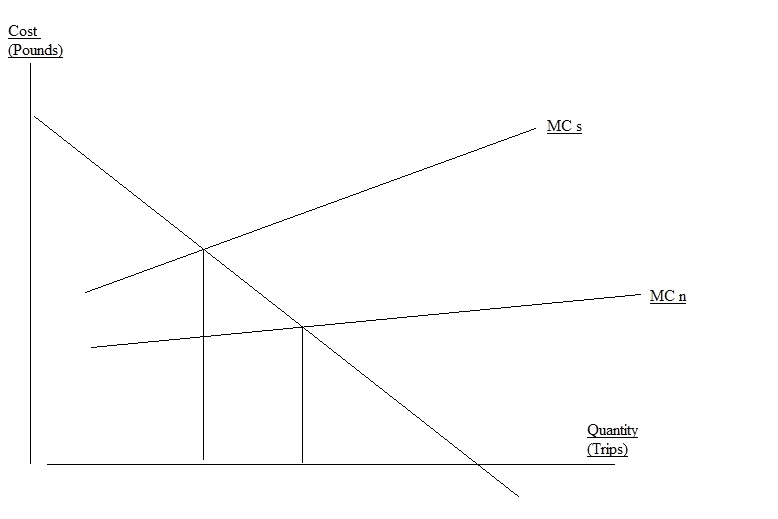

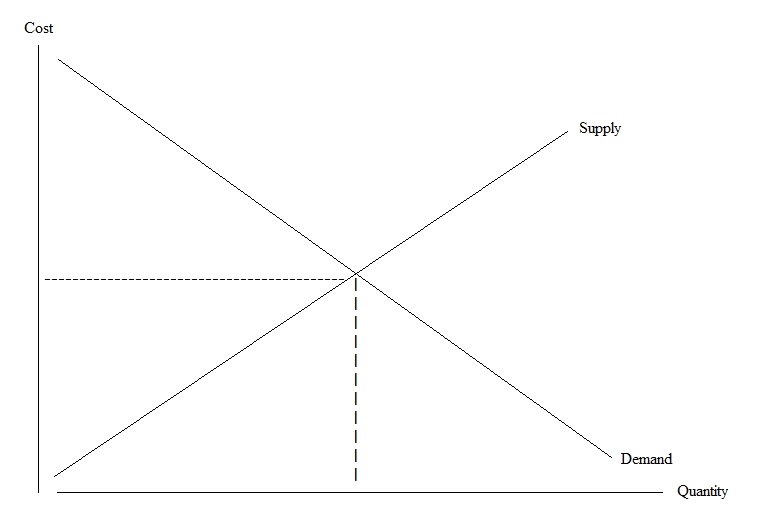

The figure above shows the costs of negative externalities added into the equation of road use. The congestion costs reflect the type of external effects of using said road. For motorway congestion, the costs to the individual driver are the time costs of travel, plus vehicle operation costs (quantity of petrol used). The costs to all drivers will increase with the number of drivers making the trip; in other words the total cost to the road owner will be the cost of holding the car on his road, plus the congestion cost this imposes on his road, external property owners and other drivers. The costs are shown diagrammatically.

In the diagram above there is a clear distinction between the costs to an individual driver (MC n) and the costs to the road owner and other drivers (MC s). We understand negative externalities when it comes to human activity, if the privatisation of roads was brought about, owners of the roads would reflect these “unseen” costs in their prices; the issue is not “market failure”, because there has never been a market for road ownership.

Another simpler way of explaining this would be as follows.

Most people understand the standard supply and demand curve, and both meeting in equilibrium.

Suppose we were to take our example of a privatised road, private property rights and external diseconomy (negative externalities) into account. The private road owner, due to him being able to reap the benefits from returns, would be looking to the long term and be seeking to maximise the value of his road. Let us assume at peak periods, he has a lot of gas guzzling lorries on his road; the excess fumes from these lorries will produce a lot more damage to his road as well as potential damages to property owners nearby. Our road owner; ceteris paribus, will include the cost of using more resources to maintain his road, that could’ve gone into other ventures into the total cost to the drivers; taking into account the scarce supply of road space during this peak time.

The additional charge for potential damages to property owners nearby, will be taking into account because if he hosts too many gas guzzlers on his road and the fumes damage their property, the road owner is the one who will receive an injunction from the courts and have to pay for damages; and so the road owner will be looking to minimise as much excess fumes produced on his road as possible, while seeking the highest profit from the use of his services (providing a road).

Okay, so how would private ownership of the ocean work?

That I must admit is far beyond my understanding. Certain private ownership is easy to comprehend; ponds and lakes as an example would be owned by those who own private parks, and they would face an incentive to maintain these ponds and lakes in order to reap the long term benefits if there were a high enough consumer value for recreational use; oceans however is where I have to put my hands up and say “it’s beyond me”.

This however does not mean that we should just leave the oceans at the mercy of the tragedy of the commons and ignore the ultimate cause because it’s hard to comprehend; property rights and what they entail evolve; the farming industry is a perfect example of how property rights evolve and become better at adapting to distinguish between different claims. It is entirely feasible to have private ownership of what is “in” the ocean while we learn how to hold private ownership over bodies of the ocean itself. Private ownership and private property rights over coral, seabeds and creatures living “in” the ocean would not just allow for the domestication of these resources, it would also incentivise the maintenance of them and create market incentives to restrict pollution so as to avoid injunctions. I will go over further details of this in the section on animal extinction.

Recycling

I talked about recycling to an extent in a previous section of this piece, explaining how recycling for the purposes of preserving resources so they don’t run out falls into the one-dimensional scarcity trap, as it ignores substitutes and the multi-specific nature of capital goods. However, as stated there is absolutely an argument to be made for recycling for the purposes of reducing pollution; particularly from non-bio-degradable materials.

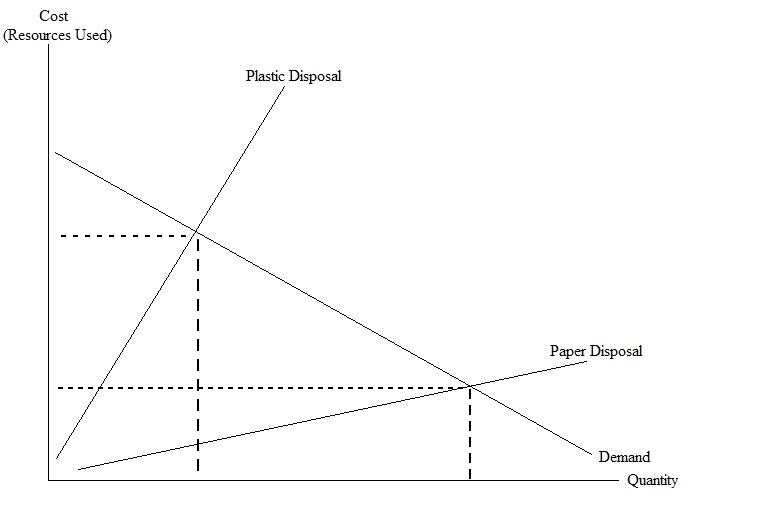

Let us take the example of paper bags vs plastic bags. Now unlike a plastic bag this should be something fun to wrap your head around (excuse my awful sense of humour).

If we were to have private rubbish collection and private rubbish dumps, then an owner of a private dump would be looking to maintain and maximise the value of his land. In order to properly dispose of a plastic bag, it takes a lot more time and resources than it does for paper. By allowing for a private market of waste disposal, the private owner would calculate the cost of disposing of the plastic into the price. This is because this creates an opportunity cost for the owner; if he uses the extra resources for disposing of a plastic bag, these are resources that could have gone into other avenues of production, and so he must reduce or remove those endeavours; in addition the extra cost for disposing of the plastic bag, is to ensure the owner can maintain the value of his land, as since the plastic bag is not bio-degradable, the pollution from it would bring greater harm to his land, and thereby reduce the value if not disposed of properly.

These factors would be expressed and signalled in the pricing mechanism. If the total cost was able to be reflected in the pricing mechanism, then instead of 1p for paper and 10p for plastic, if the total cost for disposing of the plastic was £5, then it would be reflected in the price the consumer pays as being 1p vs £5. This example is shown in the higher cost of disposing of the plastic bag and the last opportunity for the used resources reflects in a higher price to consumers, whereas the lower cost of disposing of paper and the fewer resources needed for the disposal; resulting in a reduced opportunity cost for the resources alternative uses, results in a lower price for consumers.

This cost will incentivise consumers to purchase the paper bag if their marginal utility and time frame for using the bag is expected to diminish very quickly. If however, the individual consumer values the plastic bag more than the £5, and seeks to utilise it over an extended time frame, they will be more inclined; ceteris paribus, to purchase the plastic, as it takes longer for its utility to diminish and so is able to better satisfy the consumers multiple uses.

If consumers hold long term value for the plastic bag and the majority of consumers continue to buy them, then this will create an incentive to innovate new, less costly ways of disposing of plastic bags, so the land owner does not have the expense of using multiple resources for the disposal of one plastic bag; as opposed to fewer resources for multiple paper bags, which will reduce his opportunity cost, thereby freeing up his resources to be used in more long term, profitable endeavours.

Animal Extinction

The next topic to discuss is animal extinction and how to solve it. How can the market solve the problem of animal extinction? Not all animals can be saved, as some will go extinct not by human hands but by natural selection, and it could be highly counterproductive to tamper with nature in such a way, as to play the role of mother nature; the only way to supress natural selection in the animal kingdom to avoid extinction, would be to supress dietary needs and could spell disaster for different habitats in different ways; ask yourself the question: what would the impact on habitats and food chains in the animal kingdom be, if say the dodo survived? For the sake of the topic at hand, we’ll only be discussing human impact.

Let’s ask the question: why is it the buffalo came dangerously close to extinction, yet the cow has not only never come close, but is more prosperous than ever?

The reason is the tragedy of the commons. Because nobody could own buffalo the opportunity cost of shooting one was zero, because if they didn’t kill it someone else would come along and shoot it. On the other hand for the farmer, the opportunity cost of shooting a cow is extremely high; namely he doesn’t have a cow tomorrow. This is especially true if the cow is pregnant, as then he not only doesn’t have a cow for more current productions of milk and cheese, but the killing of the baby also means he has few resources for future productions of milk.

If we were able to privately own and domesticate all animals, the opportunity cost for killing too many would be much higher to the private owner. This doesn’t mean private ownership can only fall under owning say a tiger as a pet instead of a cat, or a great white shark instead of a gold fish however; over the last few years we’ve seen a large expansion in animal conservation, where private organisations own certain animals and put them under their care; privatisation of animals would allow not just this industry to expand further, but would allow others to develop.

In a previous section I spoke about privatising creatures in the ocean; having private ownership of sharks, jellyfish and other creatures would not only remove the tragedy of the commons so as to better maintain them, but also ensure that injunctions could be brought against polluters who’s chemicals reached the privately owned creatures.

Suppose I own a factory that has an external diseconomy of spewing chemicals into the ocean, and you happen to own a square of 100 metres x 100 metres of seabed, where within this space you have coral and a host of different species of fish. If my chemicals spread into your space; thereby damaging the environment your fish and coral reside in, you’ll be able to bring me to court and seek an injunction and receive payment for damages. The risk of this; especially if I’ve already been brought to court by you, will incentive me to either spray my chemicals into an unowned area; thereby homesteading it, to cease dumping chemicals, or to invest in a filter that will ensure my chemicals can’t reach your owned space. Even in the case where I choose to homestead an unowned area, I would still have to find ways of restricting my chemicals to my homesteaded area, or risk other injunctions from my chemicals reaching other seabed owners.

“The profit motive and the incentive to maximise the value for long term, will create jobs to guard the land from those littering or damaging the land that would disturb the species located within its vicinity”

Deforestation

Trying to wrap up this piece as it is already longer than intended, we come to the final topic, that being deforestation. There are other areas to go into, however just like pollution, you can’t really talk about environmental issues without talking about deforestation; the one that always comes to mind when the word comes up, is the rainforest.

The thing to note about trees is that they fall under what is known as, renewable resource; the more demand there is for the particular resource, the more there will be of said resource; if forests were privatised, this would be fully realised.

So why is it we continue to hear about deforestation? The Tragedy of the Commons.

It is for the same reason as to why there are many species of animal that are at risk of extinction; due to there being no private owner(s), there is zero opportunity cost to be recognised from cutting down a whole forest, and no long term benefits to be reaped as returns.

Governments around the world may try to combat this by implementing a maximum amount that a company may cut down, but due to the tragedy of the commons persisting, no subjective valuations taking place, and no market pricing mechanism signalling supply and demand, companies simply take the maximum; the very essence of the tragedy of the commons is, “if I don’t take it, someone else will, so I better take all of it.”

How would the privatisation of forests work? Let us suppose that an environmentalist organisation purchases a large area of land; say 10 square miles. In order to maximise the value of its land, it will open the land up for recreational use by tourists who will pay to use the recreational facilities of the land. The profits from this venture will signal to the owners that consumers value the use of the land for recreation, and so will seek to expand the land they own, or invest in capital goods to make the trees healthier and live much longer.

If we take our private ownership of animals into account as well, the owners of the land could see profits to be made from privately owning wild animals, and so could purchase a variety of endangered animals to attract more customers for recreational use; such as red squirrels, owls, foxes etc. The profit motive and the incentive to maximise the value for long term, will create jobs to guard the land from those littering or damaging the land that would disturb the species located within its vicinity, and market arrangements with vets in order to maintain the health of the animals.

Let us then suppose I work for a factory that needs wood and I come to the land owner seeking to buy a large stock of the trees they grow and maintain.

The owner could decide to sell me stocks of trees that are away from the section of land where the animals are located. If they do this, they have fewer trees as part of their land; however the additional financial capital could go towards incorporating more animals under private ownership if consumer demand and long term gains are seen to be higher for viewing the animals. Another outcome could be the owner, with the additional financial capital could use the money to invest in a larger amount of tree seeds, so as to have a much higher return in the long term; which outcome the owner chooses will demand on their subjective value of the land and how long into the future their time preference is, with regards to the reproduction of their capital goods.

Could they sell land which occupies animals? Yes, the owner certainly could, but if the cost of rehoming the animals is great, the owner is likely to charge a lot more; a whole lot more, for trees that are based in land where the owner’s animals occupy.

I have attempted to give the reader a short (not so short) introduction to Market Environmentalism with examples of where the watermelons go wrong, and what market measures could, and should be taken. There are many other pieces of literature on the subject from economists and environmental researchers such as Professor Walter Block and Terry Lee Anderson.

In order to properly protect the environment, we require a mass privatisation of land and resources so as to remove the tragedy of the commons, and we need to relearn that private property rights; for the poor and the rich, must be protected, and not seen as petty complaining; treating property rights as “petty” or “selfish” is what has allowed horrendous laws such as eminent domain to come into existence, and they will not go until someone says the uncanny phrase, with all seriousness:

“Get off my land!”