A State of Affairs vs A Process of Discovery

Image source: AmosWEB is Economics: Encyclonomic WEB*pedia

Economics Piece by Josh L. Ascough

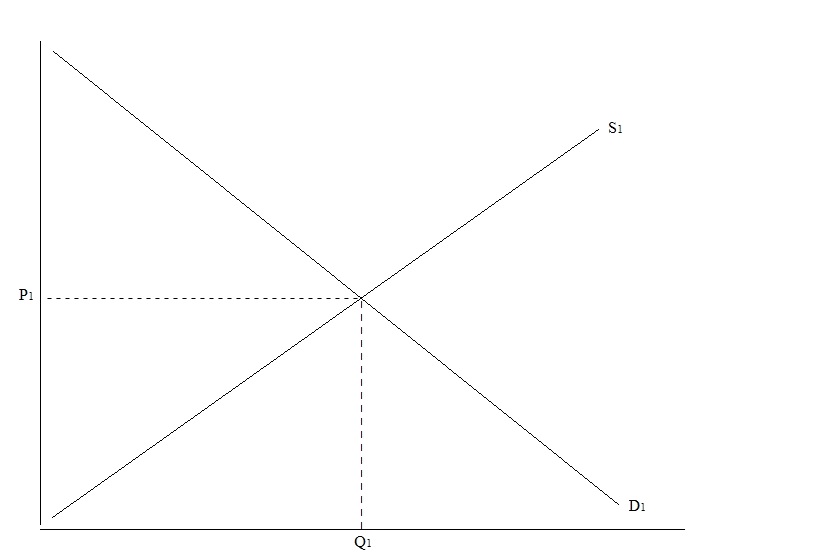

The standard theory of the market as it is expressed in the classic supply and demand curve, also known as the Marshallian curve or cross, notes that the price gravitates towards the quantity supplied by the quantity demanded, and that this ensure a state of equilibrium.

Figure 1

This is undeniably a very useful tool for giving a 30 minute talk on economics for a short and sweet answer; but it’s all wrong.

The claim that the Marshallian Cross is wrong does not invalidate the value in the basic demonstration it provides; nor the utility gotten out of a short answer to a question of market activity, but it is very much like taking a photo of a couple at point A, then a few minutes later at point B. We are skipping the market process and assuming perfect states of equilibrium. In fact, further analysis of the cross allows us to realise, that we violate the possibility of disequilibrium, and in so doing, the entrepreneur.

Let us examine this in more detail in the next few diagrams:

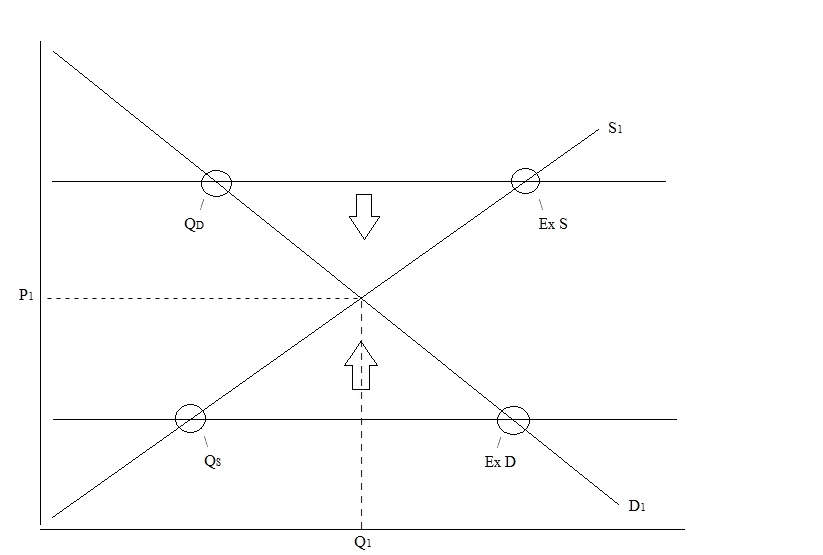

Figure 2

In our diagram we suppose, firstly, that the price is above equilibrium, where there is excess supply (Ex S) over the quantity demanded (QD). What does this do to the price? – It forces it down.

In our second point, we suppose that there is an excess demand (Ex D) over the quantity supplied (QS) this has the same effect but in reverse by forcing the price up.

Notice how under the curve, we assume two things:

- That we are consistently in equilibrium.

- That there is always a single price.

Under the Neo-Classical view, everything that is to be known is already known; man is omniscient. He has access to perfect knowledge and he need merely to analyse the data he already knows; there is no room for discovery of unknowns, nor room for the entrepreneur. The entrepreneur to our curve is an analytical pest.

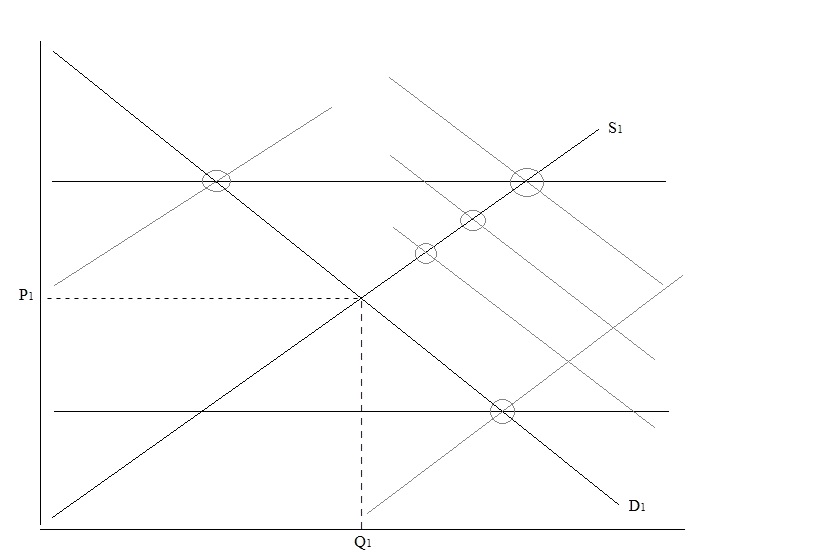

I mentioned above the assumption of there always being a single price, below we can see a quite comical examination of what is meant by this:

Figure 3

Under the equilibrium model and the Marshallian Cross, we are hypothetically assuming that with each supply curve, there is an equal demand curve running parallel to it. In fact every demand curve assumes an equal supply curve running parallel to it also; thereby consistently assuming the hypothetical to reality, that being only a single price is constant, and there is no possibility of two or more prices existing for the same product.

“It is a fundamental law of Economics that there is a single price for a product. However, this is a tendency. The reason to say it is a tendency is due to the fact that at any time, the market can be filled with ignorance”

It is a fundamental law of Economics that there is a single price for a product. However, this is a tendency. The reason to say it is a tendency is due to the fact that at any time, the market can be filled with ignorance; either optimal ignorance, whereby you know you lack information but the cost outweighs the benefit of acquiring said information, or further, the ignorance may be based in the absence of information (not knowing what you don’t know).

If there is no optimal ignorance, nor absence of information for a particular consumer good, input or resource, then the tendency for pricing signal’s to converge to a single price occurs.

To give an example, I am optimally ignorant of how to speak Korean. I would like to know how to speak and understand it, but I have analysed the cost in terms of resources and time are too great, and would be better spent on ventures I value more highly.

I would give an example of where I personally have an absence of information…but I don’t know what it is.

Further examination of this gap to which is ignored and incompatible with the equilibrium state of affairs is detailed below:

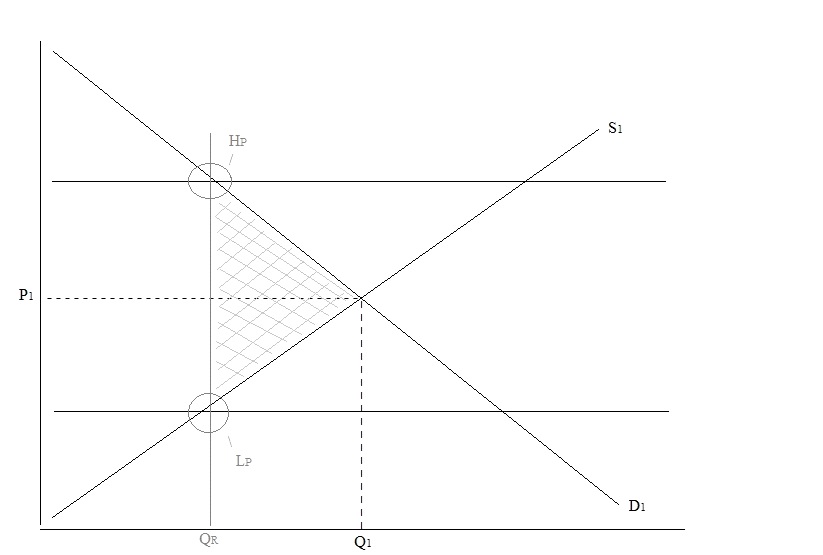

Figure 4

In the diagram shown above, under the Neo-Classical equilibrium context, we assume a quantity of QR. The question is what is the highest price that is low enough, to get consumers to buy this quantity? The answer is the top left noted as HP. Following this, what is the lowest price which is high enough to get suppliers to offer this quantity? The answer is the bottom left LP. This indicates; under an Austrian perspective rather than a Neo-Classical perspective, as shown in the greyed out section, that there is a gap.

A wider examination of this gap can be explained before moving on further:

We suppose two examples: Sellers selling a good; let’s say shoes, for £10 at the LP quadrant. Buyers who are late to the market, or hold a high marginal utility for shoes find they cannot acquire shoes, but would be more than willing to pay £17 for shoes. The second example, being that sellers selling shoes in the HP quadrant, are selling shoes for £20. Buyers with lower expendable income, or whose marginal utility is lower, cannot afford the shoes at £20, but would be willing and able to buy at £16. There is an absence of information for both buyers of the HP and LP, and sellers of the LP and HP. Sellers (buyers) of the LP are unaware they can sell (buy) at a higher price, and buyers (sellers) are unaware they can buy (sell) at a lower price.

We have a situation where two prices for the same good prevails because of ignorance.

“This is where the entrepreneur comes in. A sharp individual sees there is an unexploited opportunity by seeing the price difference. If they are sharp; as we have assumed, they will see there is opportunity for pure entrepreneurial profit”

This is where the entrepreneur comes in. A sharp individual sees there is an unexploited opportunity by seeing the price difference. If they are sharp; as we have assumed, they will see there is opportunity for pure entrepreneurial profit. The entrepreneur will buy shoes from LP for £10, and sell to buyers from both HP and LP for £15. Buyers from LP who were willing to pay £17 will gladly pay the £15, and buyers from HP who could not afford £20, but were willing to pay £16, will be able to satisfy their needs/wants by purchasing the shoes for £15. Additionally, sellers from LP will see they made a critical error as they could have sold for a higher price, and sellers from HP will see they could have sold more for a lower price; ergo, the market through entrepreneurial alertness has moved from disequilibrium to a position closer to equilibrium.

The market is in positions closer to disequilibrium positions, and the entrepreneur through the incentive for profit, discovers these gaps and brings prices closer to that of the tendency of a single price.

The market process is one of discovery; rather than an equilibrium state of affairs.

Competition Under The Market Process

Taking into consideration our examination of Neo-Classical Equilibrium, and the market as a process of discovery, what does the equilibrium state of affairs and the market process of discovery have to say about competition?

The Neo-Classical has a stark difference in terms with regards to competition as compared to the layman, and that of the process of discovery.

Under the equilibrium theory of the market as a state of affairs, the definition is classed as Perfect Competition. Perfect competition is a state of affairs, where we have an unlimited number of buyers and sellers; all sellers are selling at the exact same price, and all buyers are buying at the exact same quantities. All decisions, quantities, and production methods are known, and so everyone is constrained into this state of affairs, due to nothing else to discover.

Under perfect competition, no seller attempts to sell for a higher price, because a single market price is established and it would be suicide, and no seller equally attempts to sell for a lower price, because he knows for the set single price he can sell the exact same quantity. Furthermore, buyers do not attempt to bid a higher price because they know they can purchase the same quantity for the single price, and buyers do not attempt to acquire a lower price, because they will not acquire the products they desire.

Under the equilibrium theory of the market as a state of affairs, all quantities demanded and quantities sold are perfectly inelastic; they are static.

This theory of competition, ironically, has no semblance of any form of competition; under the layman sense or that of the market as a process of discovery.

Under the equilibrium state of affairs, everything is already known, and nobody can buy or seller at higher or lower prices, and so there is no competition.

Additionally, this state leaves no room for the entrepreneur.

I have mentioned the market as a process of discovery several times; what is it that is meant by this with regards to competition?

Competition under the market as a process, is simply freedom of entry.

“Under freedom of entry, there are no privileges in the form of institutional blockage into the market. A man can be a very successful entrepreneurial producer, but is constantly looking over his shoulder because at any point, another could enter the market”

Under freedom of entry, there are no privileges in the form of institutional blockage into the market. A man can be a very successful entrepreneurial producer, but is constantly looking over his shoulder because at any point, another could enter the market and undermine his product by selling at a price, quantity, or quality that is more appealing to consumers.

If we look back at our example of the entrepreneur buying shoes for £10 and selling for £15, because other sellers held an absence of information, and had not seen an opportunity for profit, we can understand the role competition plays in the market as a process of discovery. The market is flooded with ignorance from various economic actors, who overlook opportunities due to an absence of information and a lack of omniscience. These unseen opportunities; if our entrepreneur is sharp, are discovered, either through active search for opportunities or through a sharp eye where no search was active, and merely saw what was unseen by others.

What is required for the market to operate as a process, is decentralised discovery. What is required for competition within the market process, is freedom of entry.

Sources:

- Israel Kirzner: Competition and Entrepreneurship (pp. 10-11, 13, 20, 26, 28, 37-40.)

- Israel Kirzner: Discovery, Capitalism and Distributive Justice (pp. 8, 23-31.)

- Israel Kirzner: Competition, Economic Planning and the Knowledge Problem (pp. 9-10.)

- Entrepreneurship and the Market Process with Israel Kirzner (2011) YouTube video, added by Foundation for Economic Education [Online]

3 thoughts on “A Critique of the Marshallian Curve and Perfect Competition”

Comments are closed.