Sam Bidwell on how capitalism built Manchester.

“In c. 79AD, a Roman fort was constructed on the banks of the River Medlock, the first settlement in modern Manchester. The area remained largely depopulated and impoverished throughout the medieval period”

I\n 1700, Manchester was an obscure village of fewer than 10,000 people – by 1900, it was a metropolis, the world’s first industrial city. Its remarkable growth is testament to the power of trade, industry, and British ingenuity.

For most of its early history, Manchester was entirely unremarkable. In c. 79AD, a Roman fort was constructed on the banks of the River Medlock, the first settlement in modern Manchester. The area remained largely depopulated and impoverished throughout the medieval period. The one exception to this trend came in 1363, when a small community of Flemish weavers, from modern-day Belgium, settled in Manchester. These weavers helped to establish Manchester as a local centre for textile production – which would one day power the city’s growth.

Under Queen Elizabeth I (1553-1603), the Crown began supporting the English wool trade. The Queen’s support for the trade was so fervent that, from the 1570s until the 1590s, Englishmen were required to wear woollen caps to church on Sunday, in order to support the industry. With its existing tradition of textile production, Manchester benefitted from this support – and began exporting cloth to Europe, via London. Nevertheless, it was still an obscure Lancashire village – paling in comparison to its counterparts in neighbouring Yorkshire.

During the English Civil War (1642-1651), Manchester was a hotbed of support for the Parliament. On the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, Manchester lost Parliamentary representation, as a reprisal for its support for Cromwell. No MP was to sit for Manchester until 1832. And so, without any local government or representation in Parliament, Manchester looked set to fade into obscurity as a textiles-oriented market town. In the 1720s, Daniel Defoe described Manchester as “the greatest mere village in England”. But change was afoot.

“With its history of textile production, Manchester was well-placed to turn these raw imports into high-quality material exports. It also had ideal geography, with canals connecting the city”

By the early 18th century, Britain was in the midst of a revolution. Developments in agricultural technology meant that more food was being produced than ever before – with fewer people needed to work in farming. As a result, more people moved to the country’s urban centres. At the same time, Britain’s trade with the outside world was expanding rapidly – including in places such as India. This meant that the country had more access to new raw materials than ever before – and more markets for the export of consumer goods. Enter Manchester.

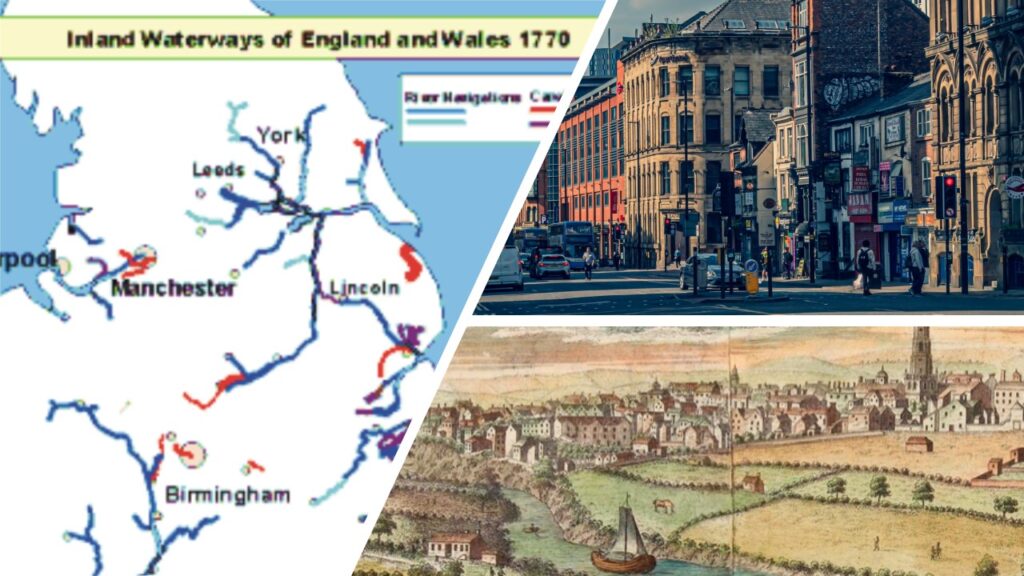

With its history of textile production, Manchester was well-placed to turn these raw imports into high-quality material exports. It also had ideal geography, with canals connecting the city to the port at Liverpool, and to the coalfields of Lancashire.

Raw goods could be imported to Manchester, processed, and then sent elsewhere for sale. The city began to boom, growing from 9,000 people in 1717 to 25,000 people in 1773. In 1781, Richard Arkwright opened the first steam-powered textile mill in the city. Throughout this period, Manchester and the surrounding towns in Lancashire were responsible for processing 32% of cotton produced globally. And the need to sell finished textile goods prompted the creation of new transport infrastructure, which connected the city to the world.

In 1761, the world’s first industrial canal opened, connecting Manchester to the coalfields at Worsley. In 1824, one of the world’s first public bus services opened in Manchester. And in 1830, the world’s first passenger railway connected Liverpool to Manchester. Canals and railways transported Manchester textiles to the port of Liverpool, allowing them to be exported. Meanwhile buses and trams enabled the city’s workforce to reach their workplaces. By 1930, Manchester Corporation Tramways operated the 3rd largest tramway in the UK.

The city also came to be known as a commercial hub, with warehouses and markets springing up across the city. In 1815, Manchester had 1,819 distinct warehouses, housing both raw materials and goods for sale. Many of these warehouses still dominate the city’s skyline today.

The jewel in Manchester’s crown was the Cotton Exchange, first opened in 1727. This vast building was the beating commercial heart of the city, a site for the sale of textiles and the financing of new industrial businesses. In 1851, it was granted the “Royal Exchange” title. In 1867, the Royal Exchange was rebuilt, with funding provided by a consortium of notable Manchester industrialists. The Exchange which still stands today began construction in 1867, and was finished in 1921 – financed, start to finish, by private donors.

“Manchester became the hub of the Anti-Corn Law League in 1839, which argued for the removal of protectionist tariffs on food”

More than almost any other city in Britain, Manchester’s urban landscape was shaped by industry, trade, and private finance. This wasn’t just the product of textile wealth. This building, on Mosley Street, was built in 1880, to house the Manchester and Salford Bank.

The city didn’t just benefit from trade liberalisation – it exported it, too. Manchester was a hub of 19th century economic liberalism. Prominent advocates of free trade, such as Richard Cobden and John Bright, were based in the city. Indeed, Manchester became the hub of the Anti-Corn Law League in 1839, which argued for the removal of protectionist tariffs on food. The Corn Laws were eventually repealed in 1846 by Conservative Prime Minister Robert Peel, partly thanks to the League’s campaigning.

“It’s also testament to the ways in which private sector growth can improve public space and enhance civil society. The city’s University, for example, was founded as a private institute”

As Manchester develops today, it’s worth remembering how the city came to exist in the first place. From obscure market town to global metropolis, Manchester’s growth was powered by building, growth, and private industry. Manchester exists because of business and capitalism. It’s also testament to the ways in which private sector growth can improve public space and enhance civil society. The city’s University, for example, was founded as a private institute in 1824, and expanded in 1846 on the basis of a bequest from textile merchant John Owens.

Rather than rejecting development, we should recognise the opportunities that change can bring. Just as our ancestors pursued growth and change, so should we. Our cities used to some of the greatest in the world – they can be again

Reproduced with kind permission of Sam Bidwell, Director of the Next Generation Centre at the Adam Smith Institute, Associate Fellow at the Henry Jackson Society, although views are his own. Sam can be found on X/Twitter, on Substack, and can be contacted at s.bidwell.gb@gmail.com. This article was originally published as a X/Twitter Thread at https://x.com/sam_bidwell/status/1869051764848373776?s=46’