“Ships with goods from around the world, particularly from across the British Empire, were onshored and processed here. By 1900, London’s docks were the busiest in the world”

Once home to the largest port in the world, London’s Docklands had fallen into disrepair by the 1970s. Today, the Docklands is one of London’s most modern, attractive areas, home to a leading financial district and even an airport.

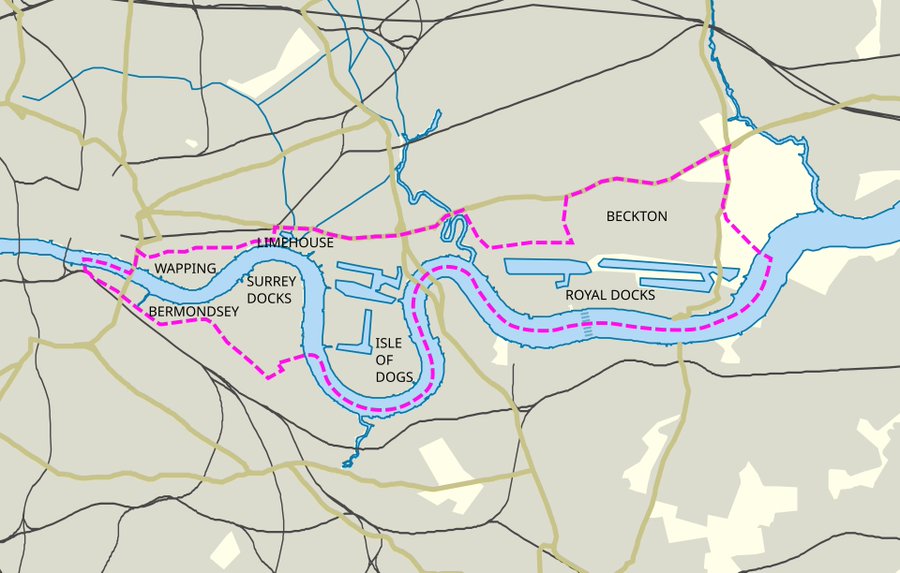

Throughout the 19th century, London’s Docklands grew rapidly, starting with West India Docks in 1802. Ships with goods from around the world, particularly from across the British Empire, were onshored and processed here. By 1900, London’s docks were the busiest in the world.

In March 1909, the separate docks were consolidated under the control of the Port of London Authority, which was responsible for management of the docks. Tens of thousands of people were employed here, and at nearby mills and factories which depended on the Docklands.

During the Second World War, the Docklands were heavily bombed in an effort to cripple Britain’s international supply chains. Much of the area’s infrastructure was destroyed, including almost 1/3 of the area’s housing. Still, the Docklands saw a brief resurgence in the 1950s.

“London’s docks were unable to accommodate the larger vessels needed for modern container shipping, and the shipping industry moved to deep-water ports like Tilbury”

Then came the shipping containers.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, shipping companies came to rely on a standardised system of shipping containers, which could be loaded and unloaded at most major global ports. This new system relied on larger vessels, and fewer human labourers.

While containerisation made international shipping cheaper and more efficient, it was terrible for the Docklands. London’s docks were unable to accommodate the larger vessels needed for modern container shipping, and the shipping industry moved to deep-water ports like Tilbury.

Between 1961 and 1971, almost 83,000 jobs were lost in the Docklands. By 1980, all of London’s docks had finally closed, leaving behind about 8 square miles of derelict land in East London. Almost all housing in the area was council owned, and crime grew rapidly.

“Ward claimed not to have a master plan – “instead, we have gone for an organic, market-driven approach, responding pragmatically to each situation.”

In 1979, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher came to power. She charged her Environment Secretary, Michael Heseltine, with addressing the decline of Britain’s post-industrial urban areas, including Docklands. Some members of her cabinet proposed to abandon the Docklands entirely.

Instead, Heseltine pursued a radically different approach. In 1981, he created the London Docklands Development Corporation, charged with spearheading a market-led revival of the Docklands. All local planning powers were handed to LDDC, despite protests from local councillors.

Planning decisions in the area would be made by LDDC. It received an initial grant of £80 million p/a, and in 1982, Heseltine created the Isle of Dogs Enterprise Zone, with no land tax, no planning restrictions, a 100% tax write-off on capital costs and a 10-year tax holiday.

The man in charge was Reg Ward, who was appointed CEO by Heseltine. The supremely pragmatic Ward claimed not to have a master plan – “instead, we have gone for an organic, market-driven approach, responding pragmatically to each situation.”

The first few years of LDDC were spent attracting investment for new riverside housing, bringing in small-scale industry (like Billingsgate Market in 1982), and opening up new office space. The proximity of Docklands to the City made it an attractive second site for businesses.

Derelict land was cleaned up and sold to developers, while the absence of local planning hurdles made the area attractive for private businesses looking to invest. By 1986, the LDDC had spent around £300m of public money, but had attracted £1.4 billion in private investment.

“DLR opened in 1987, under-budget and ahead of schedule, with subsequent expansions between 1991 and 1994”

In 1982, Ward commissioned the new Docklands Light Railway (DLR), which would make it easy to get from Docklands to central London. Running mostly on disused railway lines, DLR opened in 1987, under-budget and ahead of schedule, with subsequent expansions between 1991 and 1994.

In 1983, Ward began pushing for an airport on one of the old quays, which would cater to business travellers looking to make short-haul flights between London and Europe. Operations at London City Airport would begin in 1987.

Ward’s greatest success came in 1985, when Ward met for lunch with American-Swiss financier Michael von Clemm. Von Clemm was interested in opening a restaurant in the area – but upon visiting, realised that Docklands would be a prime location for office space.

“Canary Wharf accounts for 67,000 finance sector jobs, putting it ahead of Frankfurt as a banking centre”

Ward worked with Von Clemm to draft a proposal for a new business district, taking advantage of the area’s lack of red tape. In 1988, the project was sold to Canadian developers Olympia & York, with the first buildings finished in 1991. This development is known as Canary Wharf.

Canary Wharf accounts for 67,000 finance sector jobs, putting it ahead of Frankfurt as a banking centre – and it’s no longer an office monoculture. Count in the hotels, shops and restaurants, and Canary Wharf employed around 120,000 people, pre-pandemic.

The LDDC began a staged withdrawal in 1994, and was formally wound up in 1998. Planning powers were handed back to local councils, and the area’s special tax incentives were gradually rolled back. But what Heseltine, Ward, and others had achieved was incredible.

Once-derelict Dockland had been revitalised, with attractive riverside housing, a shining new financial district, an airport, and a local transport system. For most of its history, LDDC managed to do this almost entirely by attracting private investment.

LDDC even managed to reverse a population slump in the area that had begun in the early 1900s, encouraging upwardly mobile ‘yuppies’ to take their first step on the property ladder in the attractive riverside communities of the Docklands.

“decline is not inevitable – with ambitious, pro-growth policies, we can achieve incredible things”

What can we learn from Docklands?

- First, that decline is not inevitable – with ambitious, pro-growth policies, we can achieve incredible things.

- Second, that areas perform best when govts allow their natural strengths to flourish – such as Docklands’ proximity to London.

- Third, LDDC shows us the limits of localism. Local government figures, including Greater London Council Leader Ken Livingstone, hated Docklands. Critics said that LDDC was elitist and undemocratic – after all, it had the power to ignore local wishes entirely.

While the localism of the 1960s and 1970s had created poverty and decline, the efficiency and ambition of LDDC turned Docklands into one of Europe’s leading financial centres. Clean, modern, and full of potential. A sparkling sign of what is possible if we dare to dream.

Reproduced with kind permission of Sam Bidwell, Director of the Next Generation Centre at the Adam Smith Institute, Associate Fellow at the Henry Jackson Society, although views are his own. Sam can be found on X/Twitter, on Substack, and can be contacted at s.bidwell.gb@gmail.com. This article was originally published as a X/Twitter Thread at https://x.com/sam_bidwell/status/1815055102702498300?s=46