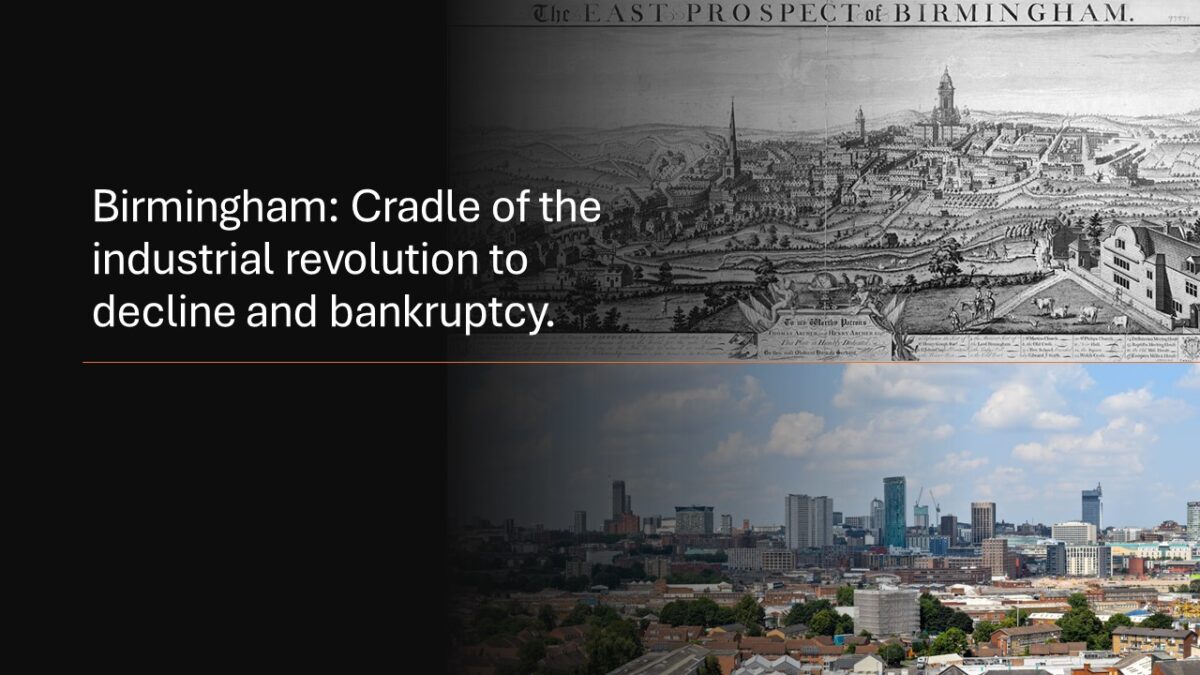

Birmingham used to be one of the world’s greatest cities. From 1954-64, service businesses around Birmingham grew faster than any other part of the country. In 1961, West Midlands households earned more on average than any other British region. This is how we ruined it…

“By 1900, Birmingham had more miles of canal than Venice. Between 1923 and 1937, the city’s population grew nearly twice as fast as the national average”

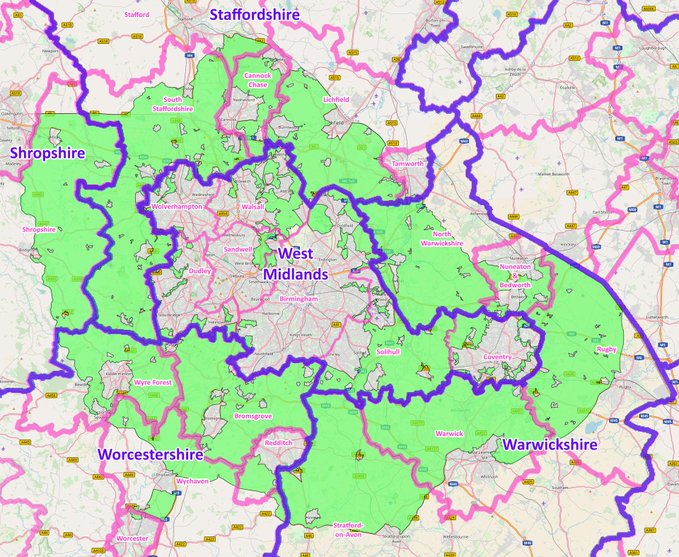

The West Midlands was one of the cradles of the Industrial Revolution. The region was the birthplace of the steam engine, while Birmingham itself was regarded as one of the world’s foremost cities. In 1890 it was described by Harper’s as “the Best-Governed City in the World”. By 1900, Birmingham had more miles of canal than Venice. Between 1923 and 1937, the city’s population grew nearly twice as fast as the national average. The compact cavity magnetron, indispensable for radar, was invented there in 1940.

But Westminster viewed this growth as a threat to other regions. The Distribution of Industry Act 1945 sought to slow industrial growth in ‘congested’ areas like the Midlands, and push it towards declining industrial cities in Northern England, Wales, and Scotland. The Act gave the Board of Trade veto power over planning applications for factories of a certain size, and created “development areas” in which the Government was charged with managing industrial estates. Walter Higgs MP, speaking during the debate:

“local government was obliged to achieve a target population of 990,000, lower than its actual 1951 population of 1,113,000”

In 1946, the Government commissioned the West Midlands Plan, which attempted to constrain Birmingham’s growth – local government was obliged to achieve a target population of 990,000, lower than its actual 1951 population of 1,113,000.

The Government wanted Birmingham to shrink.

In 1947, the Town and Country Planning Act created Industrial Development Certificates (IDC). A company had to obtain an IDC if it wanted to expand an industrial plant beyond 5,000sq ft. This gave Government control over where industry could and could not be built.

“From 1951-61, Birmingham created more jobs than any city but London, with average unemployment less than 1%”

These restrictions constrained the city’s industrial growth – but despite these controls on heavy industry, there was relatively little regulation of service businesses. From 1951-61, Birmingham created more jobs than any city but London, with average unemployment less than 1%.

“in 1964, the incoming Labour government declared Birmingham’s growth “threatening”

However, in 1964, the incoming Labour government declared Birmingham’s growth “threatening”. It restricted the development of new office space for almost two decades through the Control of Office Development (Designation of Areas) Order 1965.

And in 1975, plans for a West Midlands Green Belt were finalised, stifling the city’s housing growth. After decades of success, the Government had made it harder than ever to build new factories, new housing, and new offices in Birmingham.

The result? In the 1980s, Birmingham’s economy collapsed, with unprecedented levels of unemployment and outbreaks of social unrest. This wasn’t the result of neoliberalism – anti-growth regulation left the city vulnerable to global economic shocks.

“We have a tendency to describe fast-growing regions as “overheated” (see: modern London) – this is a dreadful instinct”

What can we learn from Birmingham?

1. We have a tendency to describe fast-growing regions as “overheated” (see: modern London) – this is a dreadful instinct. Where a local economy works, Government should enable it to flourish, rather than seeking to spread that growth thinly.

2. Britain’s regional inequality is a product of regulation, not big business. Without the above regulations, Birmingham would likely still be a thriving second city. If we want to “level up” the rest of the country, we should liberalise planning and provide cheap energy.

3. Industrial strategies don’t work. For every good example of industrial strategy, there are five examples of expensive failure. Instead of trying to direct growth, Government should be aiming to create conditions in which growth can occur naturally.

Reproduced with kind permission of Sam Bidwell, Director of the Next Generation Centre at the Adam Smith Institute, Associate Fellow at the Henry Jackson Society, although views are his own. Sam can be found on X/Twitter, on Substack, and can be contacted at s.bidwell.gb@gmail.com. This article was originally published as a X/Twitter Thread at https://x.com/sam_bidwell/status/1812177506822144055.

Main images includes a ‘View across Birmingham’. Source Smileyface on 20 July 2021, at https://www.flickr.com/photos/whataloadofmoo/51323892597/.