Image: https://pixabay.com/photos/wallet-credit-card-cash-investment-2292428/

Economic Opinion Piece by Josh L. Ascough

At the beginning of March, Rishi Sunak; Chancellor of the Exchequer, announced the first budget since the pandemic was declared.

As part of the budget and this “recovery” plan, two specific changes to taxes were announced: Corporation Tax is set to rise on large companies from 19% to 25%, and a freeze on Income Tax thresholds; bringing roughly 1 million more people into paying Income Tax, and a million more into paying at the higher rate.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies reported it is set to raise an extra £29 billion by 2025-26.

But this is fallacious at best and bad economics at worst.

One thing to note of before continuing; which will help in explaining the problems with these hikes, is that Governments’ don’t control taxes, they control tax rates. Taxes are what happen when you combine tax rates with economic behaviour. In addition corporations don’t “pay” taxes, they collect taxes; taxes to a corporation are simply an additional cost, and an increase to costs will create differing economic behaviour.

With these in mind it should become obvious at merely a glace that the tax hikes are not going to have the perceived effects the Chancellor thinks they will.

Let us address these in separate sections; from the simplest to most complex, starting with the new Income Tax thresholds.

“Most jobs paying these rates are part-time or sales assistant retail work, therefore it will have a negative financial effect on these demographics; such as single parents looking to work part time and students. Further, this will cause a hit to high-street businesses struggling to find employees”

Freezing the Income Tax thresholds will force those earning £12,500 and below to start paying Income Tax. This will inevitably lead to low income individuals to see their living standards drop further, due to the forced decrease in expendable income, many will find it more difficult to satisfy their wants/needs and see their marginal utility of goods drop. As a result a few things will happen:

- More people with no work experience or qualifications will remain and enter the benefit trap, since the credits and additional welfare assistances will be not necessarily more appealing, but more manageable for meeting expenses than the large cost to incomes, due to welfare acting as a substitute to income, rather than a supplement, which means the government will not be getting as many additional receipts as they imagine.

- Due to those earning £12,500 or lower paying Income Tax, spending by those demographics will see a decrease, which means there will be less revenue generated via the Sales Tax, and this decrease in consumption could further hurt small businesses already on the margin.

- There will be a further disincentive to work in these positions. Most jobs paying these rates are part-time or sales assistant retail work, therefore it will have a negative financial effect on these demographics; such as single parents looking to work part time and students. Further, this will cause a hit to high-street businesses struggling to find employees, and as mentioned above, will mean the government will not get as many additional receipts as they imagine.

- There will be mounted pressure to raise the minimum wage in an attempt to counteract the introduced taxes. If this occurred those unable to produce at the new rates, would find themselves laid off and unemployed; essentially making it impossible for them to find employment; increasing the unemployment rate, and, once again, decreasing the degree of receipts the government is expecting to gain.

But that is just the lower income thresholds, as mentioned above millions are expected to be pushed into the higher Income Tax rate of 40%. What can we expect the results of this will be?

Similar as mentioned above, the push up to a higher tax threshold will mean those previously paying 20% will find due to the decrease in expendable income that their living standards will decline do being able to satisfy less needs/wants, and will find their marginal utility of goods and services decrease.

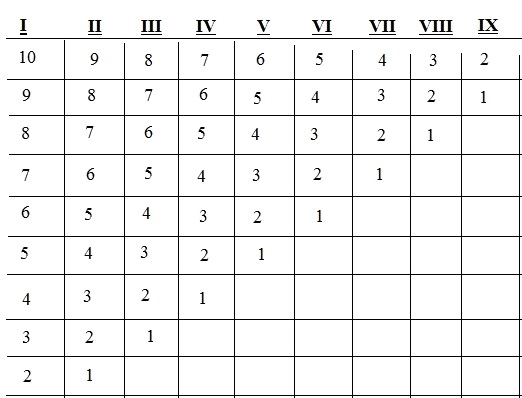

I’ve gone over this a few times in previous pieces but to reiterate, let’s illustrate what is meant.

If we look at the Mangerian representation of marginal utility we get a much clearer picture of this:

Suppose ‘A’ has an annual income of £30,000; after a progressive income tax of 20%, ‘A’ is left with £24,000. Additionally suppose ‘A’ has 9 needs/wants in order of importance for satisfaction. These are:

- Food.

- Bills.

- Clothing.

- Travel.

- Owning a Pet.

- Pet Food.

- Leisure.

- Saving.

- Holidays.

Suppose ‘A’ is only able to satisfy six of these needs/wants. Because marginal utility is based on the level of satisfaction = utility, and the lowest want = marginal, ‘A’ would do without the 9th, 8th, and 7th. Under the pushed up threshold of 40%, ‘A’ would be left with £18,000, and would have to do without the 6th, 5th, and 4th.

Now these needs/wants illustrated are not determined and can be interchanged with each other or different goods and services based the subjective values of the individual, but it still stands that the new threshold will force median earners to restrict themselves further.

This in turn has a negative feedback to the industries which provide those goods and services done without. Those industries, to which consumers pushed into higher tax thresholds have done without, will in due course see a drop in sales; not just meaning they are making fewer or no profits, but are not covering their costs, which will in turn cause further unemployment, closing of shops in locations hit hardest, and possibly lead to bad deflation; the kind of deflation which occurs due to economic downturns in production and productivity.

There are also the effects on savings and investment.

If people are leaving consumption needs/wants unsatisfied in order to satisfy those needs/wants that hold a higher marginal value, then we can expect those median earners to reduce the amount they are saving; since current consumption is more intense than ability and/or desire to save for future consumption, once pushed into an Income Tax threshold of 40%

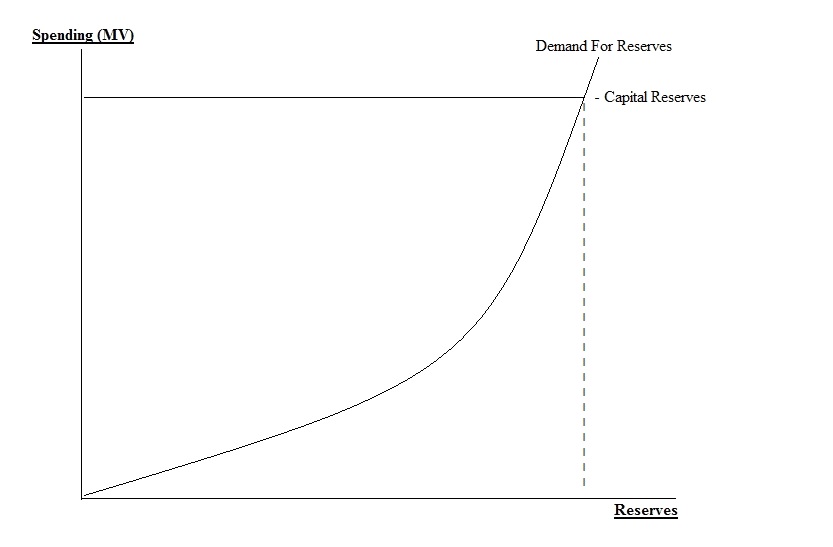

In such an instance MV (money velocity) would be at a high, indicating people’s time preference for current consumption. This would mean the banks would not be able to lend as much, and the interest rate would have to rise; signalling to businesses and entrepreneurs that now is a bad time to expand their capital goods or bring new markets to consumers.

This would mean fewer businesses will be able to diversify themselves through expansion, leading to a slower growth in production and job creation.

“Does it sound like a bad budget? …The Corporate Tax is scheduled to rise from 19% to 25%, making it the highest rate of Corporate Tax since 1982 when the rate was roughly 30%”

Does it sound like a bad budget? Well we haven’t even gotten into the Corporate Tax and things are about to get a lot worse with even more negative feedbacks.

The Corporate Tax is scheduled to rise from 19% to 25%, making it the highest rate of Corporate Tax since 1982 when the rate was roughly 30%.

This will have a variety of negative effects, depending on how businesses respond to the rise in corporate tax; a combination of behaviours could be expected, considering the harm to which the economy has been subject to due to the lockdown and other government policies.

While the budget states that it is only large corporations that will see their tax rate increase, it is still to have a negative effect on small businesses; but we’ll get to that as we go along.

As stated earlier, not only are taxes what happen when combining tax rates with economic behaviour, but corporations don’t “pay” taxes, they collect them. What should be heard when “we’re raising taxes on corporations” is uttered, is:

“We’re going to use corporations as a funnel for higher rates of collection”.

With this in mind what behaviours are to be expected from the funnelling of taxes via corporations?

Let’s talk about consumer prices first, because this links closest to what was mentioned with regards to Income Tax.

One way economic behaviour can respond to an additional cost is to see an increase in consumer prices. This would mean alongside the new Income Tax thresholds, many consumers will find their cost of living rising sharply, and have to readjust their optimal ranking of goods and services they hold a utility for, to which would mean there would be additional needs/wants left unsatisfied.

This, similar to what was stated earlier, would mean businesses would not see as high profits as the government is counting on, and government receipts via the Corporate Tax would see a decrease, because people are seldom able or willing to spend as much.

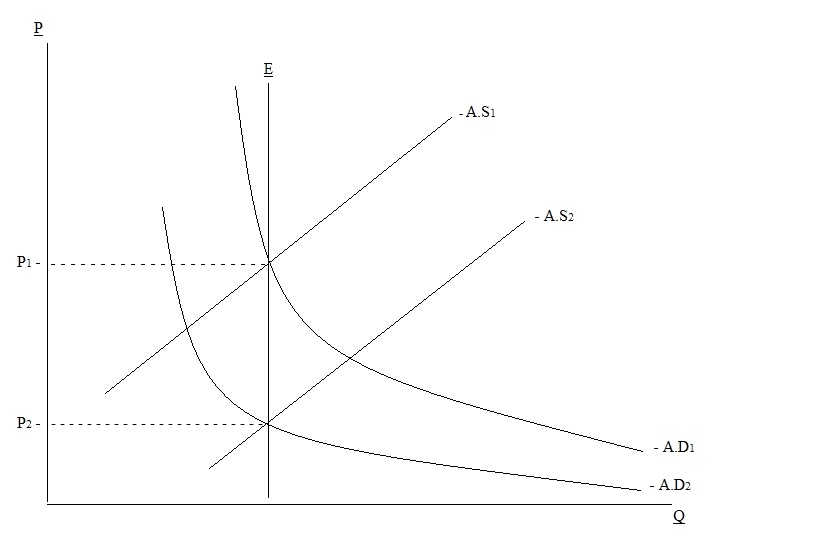

This large reduction in spending, alongside a possible withholding from investment into expansion, is what could lead to the bad kind of deflation. A basic outline can be seen below.

In the illustration shown above we see a basic example of a fall in spending. Aggregate Demand (A.D1) shifts downwards to the curve of A.D2. This causes output to fall also, as displayed by Aggregate Supply (A.S1) shifting downwards to A.S2. This leads to the price of goods in turn falling from P1 to P2.

It must be stressed that to class this fall as a good thing would be in the negative. Remember, these falls in prices and demand aren’t because an optimal quantity of goods have satisfied consumer wants/needs for the complete period in which they wish to utilise them; it is because overall spending has fallen, and because output has shrunk. Which means there are expansions of capital goods that have been abandoned, and in order to offset the cost, wages have to be cut, workers laid off and prices have to fall.

It is a somewhat similar story with regards to other behaviours that can be an outcome of the tax hikes.

A rise in tax rates on profits would mean in order to offset the additional cost, wages could see a decline. This brings us back to what was mentioned earlier about lower expendable income in a cycle:

Income Tax Rate Rises – Less Expendable Income – People Spend Less – Corporate Tax Rate Rises – Wages Fall/Prices Rise – Cost of Living Rises – People Spend Less – Cost to Businesses Rise/Revenue Falls – Outputs/Wages Fall.

Leading to, as mentioned before, the government finding its receipts are not as plentiful as they anticipated; fewer receipts via the Sales Tax, Corporate Tax, and, if workers are laid off, Income Tax.

Another Area to talk about is the process of production and entrepreneurship.

Capital and production are forward-looking, multi-period processes. The process of production is not a simple, pre-determined static motion; entrepreneurial producers set plans in motion during set periods and can have these changed, moved forward as they originally anticipated, or at worst abandoned at the difference stages of completion.

To go into more detail, let us suppose the following:

Suppose I hold a claim to wheat seeds. I wish to plant the seeds and grow wheat in order to make bread, so I search to purchase land that is suitable for my purposes. I find a landowner and agree to pay him with a portion of the funds I receive from selling the wheat, plus interest.

After time has passed and the wheat is fully grown, the first period of my plan is complete. I discover there is a high demand for vodka, and so must make the choice whether to continue with the production of bread, produce vodka, or sell my wheat to those who produce vodka. I finally decide on the selling of the raw wheat itself.

After selling my wheat to bread makers and vodka producers, I pay the land owner and must make the following decision:

Do I continue to pay him for the use of this land; or, with my revenue, do I buy the land outright, and rent it to producers looking to produce wheat for bread and vodka, knowing that this is an industry in high demand. Or, alternatively, do I buy the land outright, and continue to produce wheat for high demand industries without needing to pay rent?

Ultimately I decide to buy the land outright; initially to produce wheat for bread and vodka. However, I see consumers are favouring a competitor for bread, and demand for vodka is not being met due to most wheat producers selling to this bread maker for possible higher returns. Finally I decide to dedicate my wheat production to the manufacturing of vodka alone; specialising in one particular area of the market.

The point of this long winded story, is to illustrate that at any time, initially perceived long-run plans for the market can change. That the market process is not an indefinite, unchanging plan, but that the plans producers make are multiple; in varying periods of production and can change from initial desired outcomes.

Because the process of production is a long-run, multi-period one, added externally imposed costs do not merely effect the outputs by seeing a smaller scale of outputs, they can and will effect different periods of production; which can in turn, effect the employment of those in the production of goods of higher order. The market is interdependent, and so negative shocks to one period of the process can and will send negative feedback to earlier stages of production.

I gave mention earlier to how the rise in Corporate Tax rates would have an effect on small businesses and not just larger businesses; this, like most of what we’ve talked about here, would be a knock on effect.

How so?

Small businesses unlike larger, more international businesses don’t have the ability to branch out; nor large stocks of capital to diversify themselves and rely on other companies to provide products for them to line the shelves with. Small businesses don’t have the means to produce output, nor do they have large quantities of capital goods to utilise input materials should a supply run short. If the higher rate of Corporate Tax causes a reduction in outputs, or, at the least, a slower expansion of production, then small businesses; particularly small, family owned retail shops, will find the already produced, output stock they can store for sale will be heavily reduced or have a higher cost.

A higher Corporate Tax rate may not hurt small businesses directly, but it hurts them indirectly by reducing the amount of outsourced goods they can afford; requiring them to lower their stock or increase their prices, making them more at risk of shutting down.

“The Laffer Curve theorises that there are two peak points of a tax rate, at which the government would receive 0 revenue. At the top is a 100% tax rate, at which the government would receive zero revenue due to driving out any and all investments, wages, savings and other means of generating wealth”

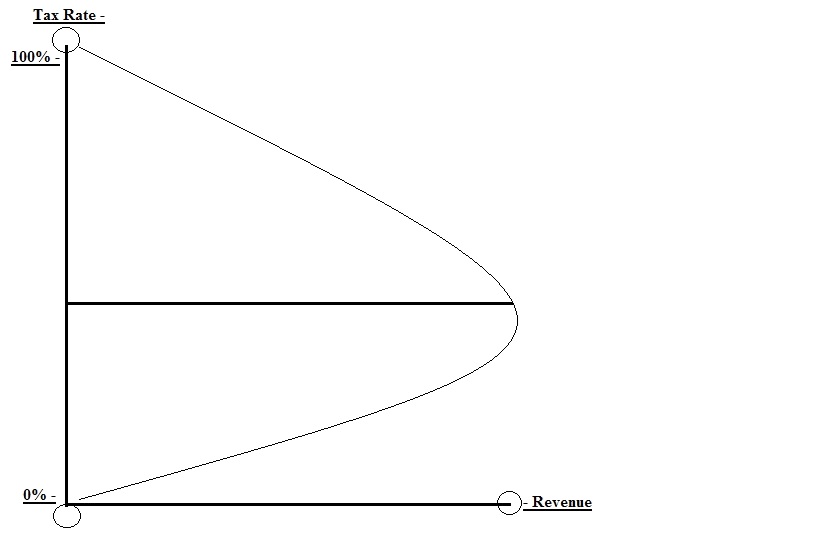

Before concluding I want to briefly talk about the Laffer Curve.

The Laffer Curve theorises that there are two peak points of a tax rate, at which the government would receive 0 revenue. At the top is a 100% tax rate, at which the government would receive zero revenue due to driving out any and all investments, wages, savings and other means of generating wealth. At the bottom is 0% tax rate, at this point the government receives zero revenue because it places no rate of tax on its citizens and their activities.

While it shows at both these points the government receives 0 revenue, each peak point has different effects on citizens. At the top point the citizens’ economic activity would be non-existent and be put into positions of poverty, while at the bottom point the citizens economic activity, productivity and accumulation of wealth would be at its maximum optimal level; higher tax rates slow economic activity, lower tax rates accelerate economic activity.

So why, even if we believe what has been discussed here to be the worst of a worst case scenario, hasn’t the government seen these issues?

Well the shortest answer I can give without taking too much more of the readers time, is that it is a theoretical error with Mainstream Economics, viewing the economy as a static period; merely a mathematical formula not affected by human choice, values, ambitions and action. It is viewing economic activity as if it is not affected by externally imposed costs; that the economic actors will bring about a certain level of activity regardless of how high a tax rate is increased. It is seeing you have 12 eggs to make a large cake, taking 8 and believing you can make the exact same sized cake with 4 as you could with 12.

There is little excuse for a fallacious budget. Even if taking the assumption that such a bad budget was desperately brought in, in order to expand the governments revenue there are two problems with this:

- Taking a larger amount from a small pie is not the same as taking a smaller amount from a large pie. Or, in money terms: There’s a difference between taking, say, 5% of £300 million, and 20% of £3 million.

- The government already has a large revenue stream. Revenue isn’t the government’s problem, and I’m going to show this briefly before concluding:

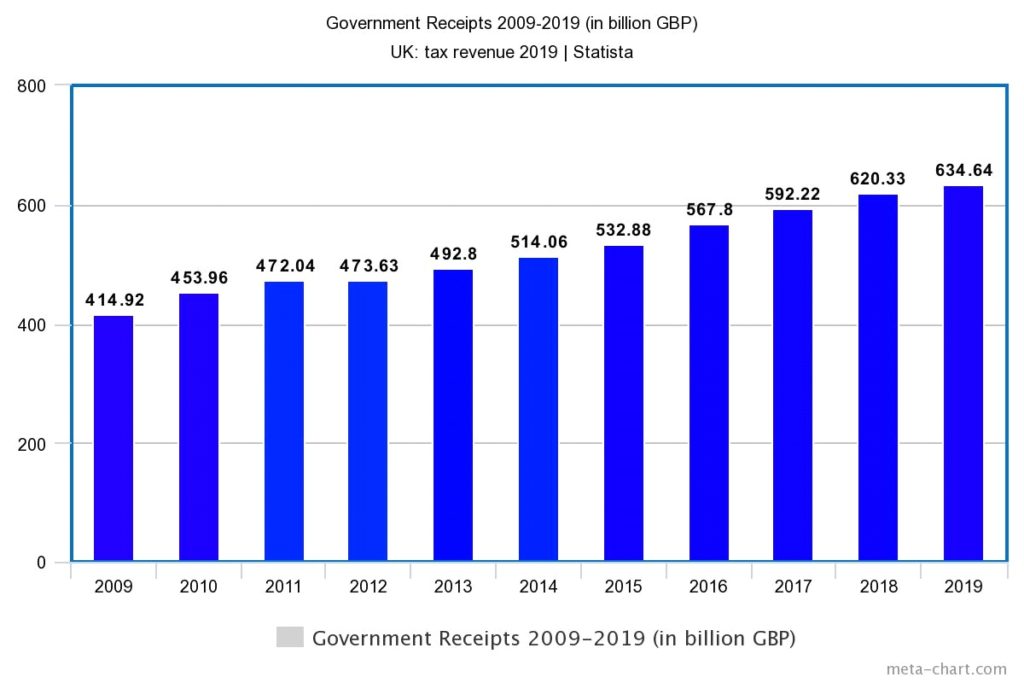

Let us compare Government debt with Government receipts; the amount of money the Government collects in a year from all sources.

If we give the Government some leeway on its debt for the year 2020 and take a look at this ratio from the year 2019, we see the following. First it is important to look at the revenue streams from the financial years of 2009 to 2019.

As is shown, the Government receipts in the financial year of 2019 were at 634.64 billion GBP; an increase of 52.95% since the year 2009.

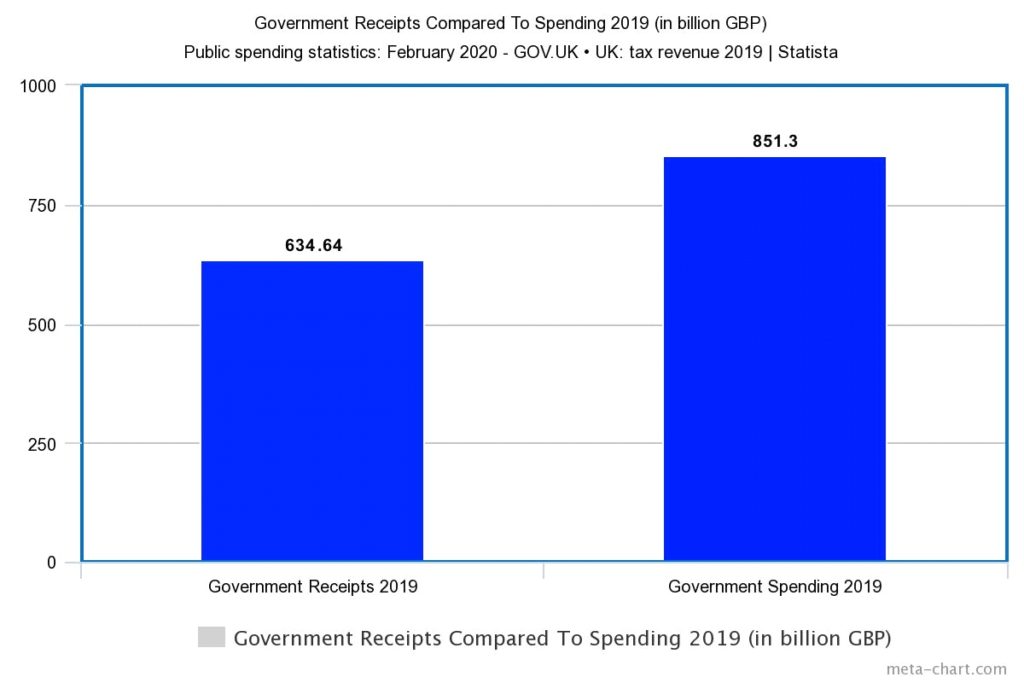

Next we look at the Government receipts compared to Government spending for the year 2019.

Government spending compared to receipts, was 851.3 billion GBP; which equates to roughly 34.13% higher than all sources of revenue collected by the Government.

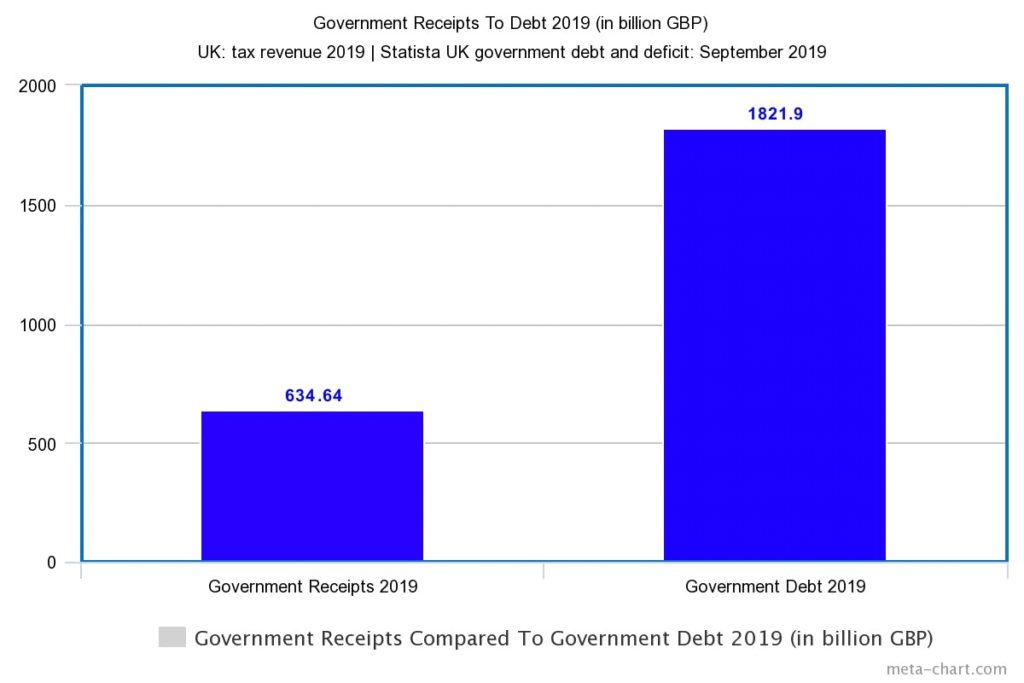

Finally let’s look at the Government receipts for the year 2019 as compared to the debt as it stood in 2019.

“The Government doesn’t have a revenue shortage problem; the Government has a spending spree problem.

If the government was looking to have economic recovery, slowing down that recovery is certainly a strange way of doing it”

In quite startling results the government debt in 2019, stood at 1821.9 billion GBP; or 1.8 trillion. The government debt is 187.07% higher than the Government receipts collected from all sources.

The Government doesn’t have a revenue shortage problem; the Government has a spending spree problem.

If the government was looking to have economic recovery, slowing down that recovery is certainly a strange way of doing it; to say the least in the most polite way possible. if the Chancellor was serious about recovery, and giving the private sector a strong push off the ground, he would’ve done well to have drastic reforms to the tax system; particularly Income Tax and Corporate Tax, into low, flat rate taxes of 5% and 10%.

Politicians like to talk a lot about the private sector giving back to the public, but for a year, the private sector has made huge sacrifices; sometimes willingly, sometimes forced on to it, in order to keep the public sector afloat; perhaps then, it’s time the public sector and the government, gave back to the private… something other than more debt, preferable.